“Never regret thy fall,

O Icarus of the fearless flight

For the greatest tragedy of them all

Is never to feel the burning light.”

Oscar Wilde

*Photographs by Anthony Gayton

Icarus and Daedalus, Frederic Leighton,1869

“…Too venturous poesy O why essay

To pipe again of passion! fold thy wings

O’er daring Icarus and bid thy lay

Sleep hidden in the lyre’s silent strings,

Till thou hast found the old Castalian rill,

Or from the Lesbian waters plucked drowned Sappho’s golden quill!…”

Charmides (excerpt)

Oscar Wilde

1881

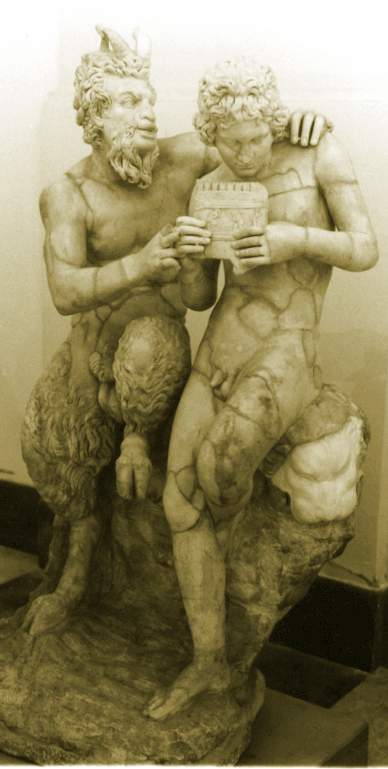

Pan teaching his eromenos, the shepherd Daphnis, to play the pipes.

Pan teaching his eromenos, the shepherd Daphnis, to play the pipes.

Second century AD Roman copy of Greek original c. 100 BC, found in Pompeii

I

O goat-foot God of Arcady!

This modern world is grey and old,

And what remains to us of thee?

No more the shepherd lads in glee

Throw apples at thy wattled fold,

O goat-foot God of Arcady!

Nor through the laurels can one see

Thy soft brown limbs, thy beard of gold,

And what remains to us of thee?

And dull and dead our Thames would be,

For here the winds are chill and cold,

O goat-foot God of Arcady!

Then keep the tomb of Helice,

Thine olive-woods, thy vine-clad wold,

And what remains to us of thee?

Though many an unsung elegy

Sleeps in the reeds our rivers hold,

O goat-foot God of Arcady!

Ah, what remains to us of thee?

II

Ah, leave the hills of Arcady,

Thy satyrs and their wanton play,

This modern world hath need of thee.

No nymph or Faun indeed have we,

For Faun and nymph are old and grey,

Ah, leave the hills of Arcady!

This is the land where liberty

Lit grave-browed Milton on his way,

This modern world hath need of thee!

A land of ancient chivalry

Where gentle Sidney saw the day,

Ah, leave the hills of Arcady!

This fierce sea-lion of the sea,

This England lacks some stronger lay,

This modern world hath need of thee!

The Painter of Pan’s Dionysiac woman, on the Kolonettenkrater in the Altes Museum, Berlin

The Painter of Pan’s Dionysiac woman, on the Kolonettenkrater in the Altes Museum, Berlin

Then blow some trumpet loud and free,

And give thine oaten pipe away,

Ah, leave the hills of Arcady!

This modern world hath need of thee!

Oscar Wilde

The Great God Pan, Frederic Leighton, 1860

The Great God Pan, Frederic Leighton, 1860

The Great God Pan is a novella written by Arthur Machen. A version of the story was published in the magazine The Whirlwind in 1890, and Machen revised and extended it for its book publication (together with another story, The Inmost Light) in 1894. On publication it was widely denounced by the press as degenerate and horrific because of its decadent style and sexual content, although it has since garnered a reputation as a classic of horror. Machen’s story was only one of many at the time to focus on the Greek God Pan as a useful symbol for the power of nature and paganism. The title was possibly inspired by the poem A Musical Instrument published in 1862 by Elizabeth Barrett Browning, in which the first line of every stanza ends “… the great god Pan.”

Literary critics such as Wesley D. Sweetser and S. T. Joshi see Machen’s works as a significant part of the late Victorian revival of the gothic novel and the decadent movement of the 1890s, bearing direct comparison to the themes found in contemporary works like Robert Louis Stevenson‘s Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, Bram Stoker‘s Dracula, and Oscar Wilde‘s The Picture of Dorian Gray. At the time authors like Wilde, William Butler Yeats, and Arthur Conan Doyle were all admirers of Machen’s works.

“A few days ago Rodin began the portrait of one of your most remarkable authors, which promises to become something quite extraordinary…”

Letter of Rainer Maria Rilke,

April 9th, 1906.

Bust of Sir George Bernard Shaw by Auguste Rodin

Bust of Sir George Bernard Shaw by Auguste Rodin

The Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw managed to impress the young Rainer Maria Rilke merely by sitting before the former poet’s idol and master, Auguste Rodin. “He stands excellently,” Rilke gushed in his letters, “with an energy in his keeping still and with such an absolute giving of himself to the hands of the sculptor.” Rainer, though a background figure at the time, and positively Lilliputian in reputation compared to the eminence of Shaw and Rodin, practically flung himself headlong into their graces. That’s not to suggest that he was sycophantic; merely, naturally, that this young Bohemian wanderer was excited to find himself in orbit with two of the century’s greatest minds and hands. “This personality of Shaw’s,” Rilke continues in his letter, “and his whole manner makes me desirous of reading a few more of his books … would sending me a few of his books be justified if I say that I am hoping to write a little thing about him?”

Rodin photographed by George Bernard Shaw

“Rodin had no interests outside his art,” Shaw later said. “He was the most painstaking sculptor I have ever met. I gave something like thirty sittings, in as many consecutive days, at his studio in Meudon. Rodin took a large number of profiles, adjusting my face by a fraction of an inch for each—spinning my head round by degrees. He took an immense number of measurements and made so many pencil marks on the clay that he used up three pencils before the sittings were over … Somewhere near the thirtieth day I asked him when the bust would be finished. ‘Finished?’ he said in surprise; ‘why, I have hardly begun!’”

“Yesterday,” Rilke wrote in a letter dated April 19th, “he seated Shaw in a cunning little child’s armchair (that ironic and by no means uncongenial scoffer was greatly entertained by all this) and cut off the head of the bust with a wire.” Rilke added that, rather than being perturbed by the sight of his effigy being cut into pieces, “Shaw, whom the bust was already remarkably like, in a superior sort of way, watched this decapitation with indescribable joy.”

“Rodin was a passionate collector of pebbles. He would go out to the beach, or into the street, and pick up any pebble presenting in his imagination a resemblance to human features. He also collected large pieces of rock, and for the same reason. At first he accommodated these treasures in glass cases in his own house, then, when the collection grew too big for that, he rented a separate building for them. It was a sign of the highest favour on the part of Rodin to present someone with one such pebble or piece of rock.”

~ George Bernard Shaw.

Shaw continued: “From the clay model he made two casts, one in marble and one in bronze. The bronze one is in my possession, while the marble one is in Dublin. For some unfathomable reason my friends and admirers have covered this marble bust with their pencilled signatures.”

Of Shaw, Rilke concluded that he “is a man who has a very good way of getting along with life, of putting himself into harmony with it … Proud of his works, like Wilde or Whistler, but without their pretentiousness, proud as a dog is proud of his master.”

Photograph by Michael Vincent Manalo

Photograph by Michael Vincent Manalo

THE western wind is blowing fair

Across the dark Ægean sea,

And at the secret marble stair

My Tyrian galley waits for thee.

Come down! the purple sail is spread,

The watchman sleeps within the town,

O leave thy lily-flowered bed,

O Lady mine come down, come down!

She will not come, I know her well,

Of lover’s vows she hath no care,

And little good a man can tell

Of one so cruel and so fair.

True love is but a woman’s toy,

They never know the lover’s pain,

And I who loved as loves a boy

Must love in vain, must love in vain.

O noble pilot tell me true

Is that the sheen of golden hair?

Or is it but the tangled dew

That binds the passion-flowers there?

Good sailor come and tell me now

Is that my Lady’s lily hand?

Or is it but the gleaming prow,

Or is it but the silver sand?

No! no! ’tis not the tangled dew,

’Tis not the silver-fretted sand,

It is my own dear Lady true

With golden hair and lily hand!

O noble pilot steer for Troy,

Good sailor ply the labouring oar,

This is the Queen of life and joy

Whom we must bear from Grecian shore!

The waning sky grows faint and blue,

It wants an hour still of day,

Aboard! aboard! my gallant crew,

O Lady mine away! away!

O noble pilot steer for Troy,

Good sailor ply the labouring oar,

O loved as only loves a boy!

O loved for ever evermore!

Oscar Wilde

The Remembrances of the Soul, photograph by Michael Vincent Manalo

HOW steep the stairs within Kings’ houses are

For exile-wearied feet as mine to tread,

And O how salt and bitter is the bread

Which falls from this Hound’s table,—better far

That I had died in the red ways of war,

Or that the gate of Florence bare my head,

Than to live thus, by all things comraded

Which seek the essence of my soul to mar.

“Curse God and die: what better hope than this?

He hath forgotten thee in all the bliss

Of his gold city, and eternal day”—

Nay peace: behind my prison’s blinded bars

I do possess what none can take away,

My love, and all the glory of the stars.

Oscar Wilde

Photograph by Michael Vincent Manalo

Photograph by Michael Vincent Manalo

I am the ghost of Shadwell Stair.

Along the wharves by the water-house,

And through the cavernous slaughter-house,

I am the shadow that walks there.

Yet I have flesh both firm and cool,

And eyes tumultuous as the gems

Of moons and lamps in the full Thames

When dusk sails wavering down the pool.

Shuddering the purple street-arc burns

Where I watch always; from the banks

Dolorously the shipping clanks

And after me a strange tide turns.

I walk till the stars of London wane

And dawn creeps up the Shadwell Stair.

But when the crowing syrens blare

I with another ghost am lain.

Wilfred Owen

This poem was first drafted at Scarborough between January and February 1918, then in July or August it was revised just prior to Owen’s tragic death. Its message is cryptic, bound up with Wilfred’s sexuality and his association with gay literary figures such as Robert Ross (Oscar Wilde‘s friend), Osbert Sitwell and Charles Scott Moncrieff (the translator of Marcel Proust) who, along with Siegfried Sassoon, were doing much to forward Wilfred’s career as a poet.

Portrait by Russel Wong, taken in Raffles Hotel, Singapore, 1997

Portrait by Russel Wong, taken in Raffles Hotel, Singapore, 1997

“A kind of Seventh Avenue Oscar Wilde” Time magazine called Isaac Mizrahi in 1998, after the shocking news broke that the superstar designer was closing up shop. The dimming of lights at Isaac Mizrahi & Co. marked the end of a spectacular run for the Brooklyn native, who had been a fashion and media darling since his first rave reviews more than a decade before.

Naomi Campbell, Isaac Mizrahi and Linda Evangelista. Photo by Mario Testino

Naomi Campbell, Isaac Mizrahi and Linda Evangelista. Photo by Mario Testino

Beloved both on and off the runway, the mop-haired raconteur was already a household name when he made a charmingly manic appearance in the fashion documentary Unzipped. By trailing the designer as he prepared his fall 1994 collection (conceived with the help of an Ouija board), Douglas Keeve offered a tantalizing peek behind fashion’s velvet curtain in his film. But not even the king-size force of Mizrahi’s character was enough to sustain the ride. Though his couture-luxe line of candy-color (“Pink! The new beige!”) sequined slip dresses and mink-trimmed ball skirts was admired by critics and Park Avenue princesses alike, his star was destined to fall. Isaac Mizrahi, the personality, was, it appeared, bigger than Isaac Mizrahi the brand.

Dress from Ready to Wear Spring 2012 collection

Dress from Ready to Wear Spring 2012 collection

But after spending several years on other creative endeavors (including a one-man stage production, Les MIZrahi, and a talk show), the buoyant designer that Vogue once called “Fashion’s Favorite Son” was itching to get back to his first love.

The polymath Isaac Mizrahi in his studio in Manhattan. Photo: Damon Winter

The polymath Isaac Mizrahi in his studio in Manhattan. Photo: Damon Winter

In 2003 he surprised the industry by announcing a multicategory deal with Target. Kicking the Mizrahi machine into high gear, he spun straw into gold, raking in as much as $300 million in annual sales for the bargain retailer and paving the way for it to forge lucrative partnerships with other high-profile designers. Meanwhile, Mizrahi was also working at the opposite end of the price spectrum, indulging in glorious fabrics and flamboyant silhouettes with a new haute couture line for Bergdorf Goodman. In a landmark 2004 show, Mizrahi helped popularize the high-low concept by pairing pieces from his two new lines on the same runway. “My goal is that you won’t always be able to tell the difference between what is Target and what is couture,” he said. “If it freaks out a few people now, it will turn them on a few months from now.” The risky proposition paid off, and a trend—populuxe, or luxury for all—was born.

In 2009, Mizrahi applied his golden thimble to the ailing Liz Claiborne brand with a fresh injection of his signature brights and prints. And in 2010 the tireless dynamo launched a collection for the shopping channel QVC, with a broad spectrum of products from jewelry and hats to cheesecakes adorned with his favorite tartans and polka dots.

Running like a thread through all these projects is a philosophy of bringing out the best and brightest from within his customers. To borrow the advertising slogan from his Isaac line: “Inside every woman is a star.”

Where You Stand is the upcoming, seventh studio album from Scottish rock band Travis, set to be released in August 19, 2013, on their own record label, Red Telephone Box via Kobalt Label Services. Speaking about the band’s departure from the spotlight, bassist Dougie Payne said of the release:

“You stay away as long as it takes, so you feel that hunger and desire to get back to it same as you did at the start.”

The Longest Journey.

PART 1 — CAMBRIDGE

By E.M. Forster

“The cow is there,” said Ansell, lighting a match and holding it out over the carpet. No one spoke. He waited till the end of the match fell off. Then he said again, “She is there, the cow. There, now.”

“You have not proved it,” said a voice.

“I have proved it to myself.”

“I have proved to myself that she isn’t,” said the voice. “The cow is not there.” Ansell frowned and lit another match.

“She’s there for me,” he declared. “I don’t care whether she’s there for you or not. Whether I’m in Cambridge or Iceland or dead, the cow will be there.”

It was philosophy. They were discussing the existence of objects. Do they exist only when there is some one to look at them? Or have they a real existence of their own? It is all very interesting, but at the same time it is difficult. Hence the cow. She seemed to make things easier. She was so familiar, so solid, that surely the truths that she illustrated would in time become familiar and solid also. Is the cow there or not? This was better than deciding between objectivity and subjectivity. So at Oxford, just at the same time, one was asking, “What do our rooms look like in the vac.?”

“Look here, Ansell. I’m there—in the meadow—the cow’s there. You’re there—the cow’s there. Do you agree so far?” “Well?”

“Well, if you go, the cow stops; but if I go, the cow goes. Then what will happen if you stop and I go?”

Several voices cried out that this was quibbling.

“I know it is,” said the speaker brightly, and silence descended again, while they tried honestly to think the matter out.

Rickie, on whose carpet the matches were being dropped, did not like to join in the discussion. It was too difficult for him. He could not even quibble. If he spoke, he should simply make himself a fool. He preferred to listen, and to watch the tobacco-smoke stealing out past the window-seat into the tranquil October air. He could see the court too, and the college cat teasing the college tortoise, and the kitchen-men with supper-trays upon their heads. Hot food for one—that must be for the geographical don, who never came in for Hall; cold food for three, apparently at half-a-crown a head, for some one he did not know; hot food, a la carte—obviously for the ladies haunting the next staircase; cold food for two, at two shillings—going to Ansell’s rooms for himself and Ansell, and as it passed under the lamp he saw that it was meringues again. Then the bedmakers began to arrive, chatting to each other pleasantly, and he could hear Ansell’s bedmaker say, “Oh dang!” when she found she had to lay Ansell’s tablecloth; for there was not a breath stirring. The great elms were motionless, and seemed still in the glory of midsummer, for the darkness hid the yellow blotches on their leaves, and their outlines were still rounded against the tender sky. Those elms were Dryads—so Rickie believed or pretended, and the line between the two is subtler than we admit. At all events they were lady trees, and had for generations fooled the college statutes by their residence in the haunts of youth.

But what about the cow? He returned to her with a start, for this would never do. He also would try to think the matter out. Was she there or not? The cow. There or not. He strained his eyes into the night.

Either way it was attractive. If she was there, other cows were there too. The darkness of Europe was dotted with them, and in the far East their flanks were shining in the rising sun. Great herds of them stood browsing in pastures where no man came nor need ever come, or plashed knee-deep by the brink of impassable rivers. And this, moreover, was the view of Ansell. Yet Tilliard’s view had a good deal in it. One might do worse than follow Tilliard, and suppose the cow not to be there unless oneself was there to see her. A cowless world, then, stretched round him on every side. Yet he had only to peep into a field, and, click! it would at once become radiant with bovine life.

Suddenly he realized that this, again, would never do. As usual, he had missed the whole point, and was overlaying philosophy with gross and senseless details. For if the cow was not there, the world and the fields were not there either. And what would Ansell care about sunlit flanks or impassable streams? Rickie rebuked his own groveling soul, and turned his eyes away from the night, which had led him to such absurd conclusions…”

Arkansas (titles aren’t David Leavitt‘s strong suit; this one alludes to a quotation from Oscar Wilde that doesn’t have much to do with anything) is dotted with references to E. M. Forster, who is clearly one of the author’s cynosures.

The Wooden Anniversary continues the story of two recurrent Leavitt characters, fat, hopeless Celia and handsome Nathan, the gay cad she’s always been in love with. Celia has now moved to Italy, married well, dropped 75 pounds and opened a cooking school in a glorious Tuscan farmhouse; Nathan is a widow and a mess. But the changes are only superficial: Celia, remembering the insults she once had to endure — ”Oh, men used to call me a cow all the time” — maintains that a formerly fat person, ”in her mind at least, will always be fat,” and Mr. Leavitt goes out of his way to second her. By the end of the story, Nathan has stolen her handsome Italian lover, and Celia has run away and been reincarnated as a cow. (Seriously.) The nakedness of the gay wish-fulfillment fantasy, even the extravagant misogyny, might carry a malicious charge if Mr. Leavitt were having some fun with his characters — if he had the nerve to mock them as coldly and tranquilly as, in the first story, he mocks himself. The impulse is certainly there (a cow?), but instead, for the most part, we have to suffer with them.

“All women become like their mothers. That is their tragedy. No man does. That’s his.”

Oscar Wilde

The Importance of Being Earnest

Mme. Isabelle Cardamone, Christian Dior’s mother

Mme. Isabelle Cardamone, Christian Dior’s mother

Yves Saint Laurent and Mme. Lucienne Mathieu

Yves Saint Laurent and Mme. Lucienne Mathieu

Tommy Hilfiger and Mrs. Virginia

Tommy Hilfiger and Mrs. Virginia

The lady in the portrait is Doña María Cristina Passios, Carolina Herera’s (née María Carolina Pacanins Niño) mother

Mrs. Herrera at five years old with her mother in San Sebastian, Spain in 1944.

Mrs. Herrera at five years old with her mother in San Sebastian, Spain in 1944.

Linda Eastman and Stella McCartney

Linda Eastman and Stella McCartney

Georgina Chapman (from Marchesa) with her mother, Caroline Wonfor

Georgina Chapman (from Marchesa) with her mother, Caroline Wonfor

Julien MacDonald (Alexander McQueen’s successor at Givenchy) with his parents. Macdonald was taught knitting by his mother and soon became interested in design.

Julien MacDonald (Alexander McQueen’s successor at Givenchy) with his parents. Macdonald was taught knitting by his mother and soon became interested in design.

Matthew Williamson and his mum

Matthew Williamson and his mum

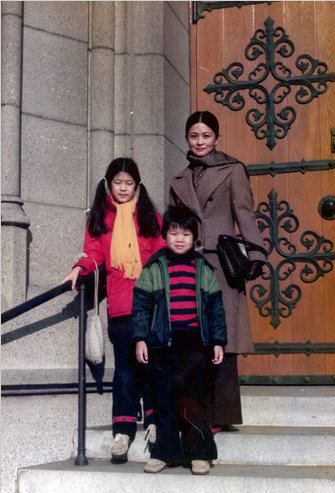

Peter Som with his mother, Helen Fong, and sister in San Francisco in 1977

Peter Som with his mother, Helen Fong, and sister in San Francisco in 1977

Duro Olowu’s mother, Inez Olowu, and father, Kayode Olowu, in 1963 in Lagos, Nigeria

Duro Olowu’s mother, Inez Olowu, and father, Kayode Olowu, in 1963 in Lagos, Nigeria

Susan Orzack and Zac Posen

Susan Orzack and Zac Posen

The Brand is named after Lázaro Hernández and Jack McCollough’s mothers’ maiden names

The Brand is named after Lázaro Hernández and Jack McCollough’s mothers’ maiden names

Thanks to The Perfumed Dandy for inciting my curiosity about this theme:

Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald, who was considered the female embodiment of the Jazz Age.

Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald, who was considered the female embodiment of the Jazz Age.

“The only horrible thing in the world is ennui, Dorian. That is the one sin for which there is no forgiveness”, advised Lord Henry Wotton, Oscar Wilde’s alter ego from The Portrait of Dorian Gray. “Intelligent people never get bored,” said a character from Ifigenia, the novel by the French-Venezuelan writer Teresa de la Parra. Diana Vreeland suggested “Never fear being vulgar, just boring.” For Sir Cecil Beaton boredom was the world’s second worst crime (the first is being a bore). On the other hand, Leo Tolstoy affirmed that boredom was the desire for desires. And everyone would agree the cure for boredom is curiosity. There is no cure for curiosity. But we all are constantly escaping from ennui and feelings like that.

Being Boring is a song composed by Neil Tennant and Chris Lowe; the Pet Shop Boys. It is the opening track and second single from Behaviour (1990), an album influenced by Depeche Mode’s Violator, which was released the same year.

It’s been said that the title apparently materialized after someone in Japan accused the duo of being boring. The title is also derived from a Zelda Fitzgerald quotation, “she refused to be bored, chiefly because she wasn’t boring”. The song is concerned with the idea of growing up and how people’s perceptions and values change as they grow older.

Due to various factors (for example, it being hard to sing), it wasn’t initially performed on 1991’s Performance Tour, leading many fans, Axl Rose among them, to complain about its omission. It is considered among the greatest, most beautiful Pet Shop Boys’ songs, despite the track’s moderate commercial success.

The Pet Shop Boys first asked photographer and film maker Bruce Weber if he would make a video with them when Domino Dancing was corning out. They met him in New York whilst recording demos with Liza Minnelli. At the time he was keen, but too busy; he was working on his second documentary film, Let’s Get Lost, (a Film about the late jazz trumpeter Chet Baker. His first film was about boxing, Broken Noses).

Weber hadn’t done a video before because of “time and circumstance, and I also fell that I really wanted to fall in love with a song. Because I knew I was going to have to listen to it about a million times (laughs). I got the tape and I loved it; I had an immediate reaction to it. I thought it had a lot of musicality and a lot to say, I loved the lyrics and really felt that it was something I wanted to be part of.” he said to Neil and Lowe.

The video is shot in black and white. In what is either a coincidence or conscious decision, two previous videos, 1989’s It’s Alright and 1990’s So Hard also lacked color. Apart from these, only 2000’s You Only Tell Me You Love Me When You’re Drunk and partially 1987’s Rent were also recorded in black and white.

The video was filmed entirely in one day at the beginning of October 1990 in a house of Long Island. Bruce Weber chose that particular setting, outside New York City, because of its association with Zelda and Francis Scott Fitzgerald. Bruce Weber explained his idea of a wonderful party. He wanted to keep away from the streets after looking at MTV a lot of video clips filmed on roads. He thought it was a corny trend.

Weber cast people he was friends with or knew the girlfriends or boyfriends of or had photographed before, including Neneh Cherry’s half-brother, musician Eagle Eye and Drena, Robert de Niro‘s daughter.

Weber incorporated a dog because “in certain French films of Renoir there was always a country animal brought as a pet. Like the Bertolucci film where Dominique Sandra comes into the house on a horse.”

Originally, the video begun with everyone on the stairs, eyes closed and Neil speaking the Zelda Fitzgerald quote to the camera. This concept turned out to be a bit too complicated so the video eventually began with a handwritten message (written by one of Bruce Weber’s friends) based on Neil’s instructions.

In a way, the video is a literal projection of the first video of the song. The video begins with with a nude swimmer and a message: “I came from Newcastle in the North of England. We used to have lots of parties where everyone got dressed up and on one party invitation was the quote ‘she was never bored because she was never boring’. The song is about growing up – the ideals that you have when you’re young and how they turn out”.

Marilyn Monroe and Truman Capote dancing at The Morocco, 1955

Marilyn Monroe and Truman Capote dancing at The Morocco, 1955

A.K.A: Abbess in High-heeled Shoes

Short story written by Truman Capote

From Music for Chamaleons

April 28, 1955

Scene: The chapel of the Universal funeral home at Lexington Avenue and 52nd Street, New York City. An interesting galaxy packs the pews: celebrities, for the most part, from an international arena of theater, films, literature, all present in tribute to Constance Collier, the English-born actress who had died three days before at age 75.

Born in 1880, Miss Collier had begun her career as a music-hall Gaiety Girl, graduated from that to become one of England’s principal Shakespearean actresses (and the fiancée of Sir Max Beerbohm, whom she never married, and perhaps for that reason was the inspiration for the mischievously unobtainable heroine in Sir Max’s novel Zuleika Dobson). Eventually she emigrated to the United States, where she established herself as a considerable figure on the New York stage as well as in Hollywood films. During the last decades of her life she lived in New York, where she practiced as a drama coach of unique caliber; she accepted only professionals as students, and usually only professionals who were already “stars”—Katharine Hepburn was a permanent pupil; another Hepburn, Audrey, was also a Collier protégée, as were Vivien Leigh and, for a few months prior to her death, a neophyte Miss Collier referred to as “my special problem,” Marilyn Monroe.

Marilyn Monroe, whom I’d met when John Huston was directing her in The Asphalt Jungle, one of her first speaking roles, had come under Miss Collier’s wing at my suggestion. I had known Miss Collier perhaps a half-dozen years and admired her as a woman of true stature, physically, emotionally, creatively; and, for all her commanding manner, her grand cathedral voice, as an adorable person, mildly wicked but exceedingly warm, dignified yet Gemütlich. I loved to go to the frequent small lunch parties she gave in her dark Victorian studio in mid-Manhattan; she had a barrel of yarns to tell about her adventures as a leading lady opposite Sir Beerbohm Tree [Max’s half-brother] and the great French actor Coquelin, her involvements with Oscar Wilde, the youthful Chaplin, and Garbo in the silent Swede’s formative days. Indeed Miss Collier was a delight, as was her devoted secretary and companion, Phyllis Wilbourn, a quietly twinkling maiden lady who, after her employer’s demise, became the companion of Katharine Hepburn. Miss Collier introduced me to many people who became friends: the Lunts, the Oliviers, and especially Aldous Huxley. But it was I who introduced her to Marilyn Monroe, and at first it was not an acquaintance she was too keen to acquire: her eyesight was faulty, she had seen none of Marilyn’s movies, and really knew nothing about her except that she was some sort of platinum sex-explosion who had achieved global notoriety; in short, she seemed hardly suitable clay for Miss Collier’s stern classic shaping. But I thought they might make a stimulating combination.

They did. “Oh yes,” Miss Collier reported to me, “there is something there. She is a beautiful child. I don’t mean that in the obvious way—the perhaps too obvious way. I don’t think she’s an actress at all, not in any traditional sense. What she has—this presence, this luminosity, this flickering intelligence—could never surface on the stage. It’s so fragile and subtle, it can only be caught by the camera. It’s like a hummingbird in flight: only a camera can freeze the poetry of it. But anyone who thinks this girl is simply another Harlow or harlot or whatever is mad. Speaking of mad, that’s what we’ve been working on together: Ophelia. I suppose people would chuckle at the notion, but really, she could be the most exquisite Ophelia. I was talking to Greta last week, and I told her about Marilyn’s Ophelia, and Greta said yes, she could believe that because she had seen two of her films, very bad and vulgar stuff, but nevertheless she had glimpsed Marilyn’s possibilities. Actually, Greta has an amusing idea. You know that she wants to make a film of Dorian Gray? With her playing Dorian, of course. Well, she said she would like to have Marilyn opposite her as one of the girls Dorian seduces and destroys. Greta! So unused! Such a gift—and rather like Marilyn’s, if you consider it. Of course, Greta is a consummate artist, an artist of the utmost control. This beautiful child is without any concept of discipline or sacrifice. Somehow I don’t think she’ll make old bones. Absurd of me to say, but somehow I feel she’ll go young. I hope, I really pray, that she survives long enough to free the strange lovely talent that’s wandering through her like a jailed spirit.”

But now Miss Collier had died, and here I was loitering in the vestibule of the Universal Chapel waiting for Marilyn. We had talked on the telephone the evening before, and agreed to sit together at the services, which were scheduled to start at noon. She was now a half-hour late; she was always late, but I’d thought just for once! For God’s sake, goddamnit! Then suddenly there she was, and I didn’t recognize her until she said…

Marilyn: Oh, baby, I’m so sorry. But see, I got all made up, and then I decided maybe I shouldn’t wear eyelashes or lipstick or anything, so then I had to wash all that off, and I couldn’t imagine what to wear…

(What she had imagined to wear would have been appropriate for the abbess of a nunnery in private audience with the Pope. Her hair was entirely concealed by a black chiffon scarf; her black dress was loose and long and looked somehow borrowed; black silk stockings dulled the blond sheen of her slender legs. An abbess, one can be certain, would not have donned the vaguely erotic black high-heeled shoes she had chosen, or the owlish black sunglasses that dramatized the vanilla-pallor of her dairy-fresh skin.)

TC: You look fine.

Marilyn (gnawing an already chewed-to-the-nub thumbnail): Are you sure? I mean, I’m so jumpy. Where’s the john? If I could just pop in there for a minute—

TC: And pop a pill? No! Shhh. That’s Cyril Ritchard’s voice: he’s started the eulogy.

(Tiptoeing, we entered the crowded chapel and wedged ourselves into a narrow space in the last row. Cyril Ritchard finished; he was followed by Cathleen Nesbitt, a lifelong colleague of Miss Collier’s, and finally Brian Aherne addressed the mourners. Through it all, my date periodically removed her spectacles to scoop up tears bubbling from her blue-grey eyes. I’d sometimes seen her without makeup, but today she presented a new visual experience, a face I’d not observed before, and at first I couldn’t perceive why this should be. Ah! It was because of the obscuring head scarf. With her tresses invisible, and her complexion cleared of all cosmetics, she looked 12 years old, a pubescent virgin who has just been admitted to an orphanage and is grieving over her plight. At last the ceremony ended, and the congregation began to disperse.)

Marilyn: Please, let’s sit here. Let’s wait till everyone’s left.

TC: Why?

Marilyn: I don’t want to have to talk to anybody. I never know what to say.

TC: Then you sit here, and I’ll wait outside. I’ve got to have a cigarette.

Marilyn: You can’t leave me alone! My God! Smoke here.

TC: Very funny. Come on, let’s go.

Marilyn: Please. There’s a lot of shutter-bugs downstairs. And I certainly don’t want them taking my picture looking like this.

TC: I can’t blame you for that.

Marilyn: You said I looked fine.

TC: You do. Just perfect—if you were playing the Bride of Frankenstein.

Marilyn: Now you’re laughing at me.

TC: Do I look like I’m laughing?

Marilyn: You’re laughing inside. And that’s the worst kind of laugh. (Frowning; nibbling thumbnail) Actually, I could’ve worn makeup. I see all these other people are wearing makeup.

TC: I am. Globs.

Marilyn: Seriously, though. It’s my hair. I need color. And I didn’t have time to get any. It was all so unexpected, Miss Collier dying and all. See?

(She lifted her kerchief slightly to display a fringe of darkness where her hair parted.)

TC: Poor innocent me. And all this time I thought you were a bona fide blonde.

Marilyn: I am. But nobody’s that natural.

TC: Okay, everybody’s cleared out. So up, up.

Marilyn: Those photographers are still down there. I know it.

TC: If they didn’t recognize you coming in, they won’t recognize you going out.

Marilyn: One of them did. But I’d slipped through the door before he started yelling.

TC: I’m sure there’s a back entrance. We can go out that way.

Marilyn: I don’t want to see any corpses.

TC: Why would we?

Marilyn: This is a funeral parlor. They must keep them somewhere. That’s all I need today, to wander into a room full of corpses. Be patient. I’ll take us somewhere and treat us to a bottle of bubbly.

So we sat and talked and Marilyn said: “I hate funerals. I’m glad I won’t have to go to my own. Only, I don’t want a funeral—just my ashes cast on waves by one of my kids, if I ever have any. I wouldn’t have come today except Miss Collier cared about me, my welfare, and she was just like a granny, a tough old granny, but she taught me a lot. She taught me how to breathe. I’ve put it to good use, too, and I don’t mean just acting. There are other times when breathing is a problem. But when I first heard about it, Miss Collier cooling, the first thing I thought was: Oh, gosh, what’s going to happen to Phyllis?! Her whole life was Miss Collier. But I hear she’s going to live with Miss Hepburn. Lucky Phyllis; she’s going to have fun now. I’d change places with her pronto. Miss Hepburn is a terrific lady, no shit. I wish she was my friend. So I could call her up sometimes and…well, I don’t know, just call her up.”

We talked about how much we liked New York and loathed Los Angeles (“Even though I was born there, I still can’t think of one good thing to say about it. If I close my eyes, and picture L.A., all I see is one big varicose vein”); we talked about actors and acting (“Everybody says I can’t act. They said the same thing about Elizabeth Taylor. And they were wrong. She was great in A Place in the Sun. I’ll never get the right part, anything I really want. My looks are against me. They’re too specific”); we talked some more about Elizabeth Taylor, and she wanted to know if I knew her, and I said yes, and she said well, what is she like, what is she really like, and I said well, she’s a bit like you, she wears her heart on her sleeve and talks salty, and Marilyn said f—you and said well, if somebody asked me what Marilyn Monroe was like, what was Marilyn Monroe really like, what would I say, and I said I’d have to think about that.

TC: Now do you think we can get the hell out of here? You promised me champagne, remember?

Marilyn: I remember. But I don’t have any money.

TC: You’re always late and you never have any money. By any chance are you under the delusion that you’re Queen Elizabeth?

Marilyn: Who?

TC: Queen Elizabeth. The Queen of England.

Marilyn (frowning): What’s that cunt got to do with it?

TC: Queen Elizabeth never carries money either. She’s not allowed to. Filthy lucre must not stain the royal palm. It’s a law or something.

Marilyn: I wish they’d pass a law like that for me.

TC: Keep going the way you are and maybe they will.

Marilyn: Well, gosh. How does she pay for anything? Like when she goes shopping.

TC: Her lady-in-waiting trots along with a bag full of farthings.

Marilyn: You know what? I’ll bet she gets everything free. In return for endorsements.

TC: Very possible. I wouldn’t be a bit surprised. By Appointment to Her Majesty. Corgi dogs. All those Fortnum & Mason goodies. Pot. Condoms.

Marilyn: What would she want with condoms?

TC: Not her, dopey. For that chump who walks two steps behind, Prince Philip.

Marilyn: Him. Oh, yeah. He’s cute. He looks like he might have a nice prick. Did I ever tell you about the time I saw Errol Flynn whip out his prick and play the piano with it? Oh well, it was a hundred years ago, I’d just got into modeling, and I went to this half-ass party, and Errol Flynn, so pleased with himself, he was there and he took out his prick and played the piano with it. Thumped the keys. He played You Are My Sunshine. Christ! Everybody says Milton Berle has the biggest schlong in Hollywood. But who cares? Look, don’t you have any money?

TC: Maybe about fifty bucks.

Marilyn: Well, that ought to buy us some bubbly.

(Outside, Lexington Avenue was empty of all but harmless pedestrians. It was around two, and as nice an April afternoon as one could wish: ideal strolling weather. So we moseyed toward Third Avenue. A few gawkers spun their heads, not because they recognized Marilyn as the Marilyn, but because of her funereal finery; she giggled her special little giggle, a sound as tempting as the jingling bells on a Good Humor wagon, and said: “Maybe I should always dress this way. Real anonymous.”)

(As we neared P.J. Clarke’s saloon, I suggested P.J.’s might be a good place to refresh ourselves, but she vetoed that: “It’s full of those advertising creeps. And that bitch Dorothy Kilgallen, she’s always in there getting bombed. What is it with these micks? The way they booze, they’re worse than Indians.”)

(I felt called upon to defend Kilgallen, who was a friend, somewhat, and I allowed as to how she could upon occasion be a clever funny woman. She said: “Be that as it may, she’s written some bitchy stuff about me. But all those types hate me. Hedda. Louella. I know you’re supposed to get used to it, but I just can’t. It really hurts. What did I ever do to those hags? The only one who writes a decent word about me is Sidney Skolsky. But he’s a guy. The guys treat me okay. Just like maybe I was a human person. At least they give me the benefit of the doubt. And Bob Thomas is a gentleman. And Jack O’Brian.”)

(We looked in the windows of antique shops; one contained a tray of old rings, and Marilyn said: “That’s pretty. The garnet with the seed pearls. I wish I could wear rings, but I hate people to notice my hands. They’re too fat. Elizabeth Taylor has fat hands. But with those eyes, who’s looking at her hands?”)

(Another window displayed a handsome grandfather clock, which prompted her to observe: “I’ve never had a home. Not a real one with all my own furniture. But if I ever get married again, and make a lot of money, I’m going to hire a couple of trucks and ride down Third Avenue buying every damn kind of crazy thing. I’m going to get a dozen grandfather clocks and line them all up in one room and have them all ticking away at the same time. That would be real homey, don’t you think?”)

Marilyn: Hey! Across the street!

TC: What?

Marilyn: See the sign with the palm? That must be a fortune-telling parlor.

TC: Are you in the mood for that?

Marilyn: Well, let’s take a look.

Palmistry photoshoot. Milton Greene. Arizona, 1956

Palmistry photoshoot. Milton Greene. Arizona, 1956

(It was not an inviting establishment. Through a smeared window we could discern a barren room with a skinny, hairy gypsy lady seated in a canvas chair under a hellfire-red ceiling lamp that shed a torturous glow; she was knitting a pair of baby booties, and did not return our stares. Nevertheless, Marilyn started to go in, then changed her mind.)

Marilyn: Sometimes I want to know what’s going to happen. Then I think it’s better not to. There’s two things I’d like to know, though. One is whether I’m going to lose weight.

TC: And the other?

Marilyn: That’s a secret.

TC: Now, now. We can’t have any secrets today. Today is a day of sorrow, and sorrowers share their innermost thoughts.

Marilyn: Well, it’s a man. There’s something I’d like to know. But that’s all I’m going to tell. It really is a secret.

(And I thought: That’s what you think; I’ll get it out of you.)

TC: I’m ready to buy that champagne.

(We wound up on Second Avenue in a gaudily decorated, deserted Chinese restaurant. But it did have a well-stocked bar, and we ordered a bottle of Mumm’s; it arrived unchilled, and without a bucket, so we drank it out of tall glasses with ice cubes.)

Marilyn: This is fun. Kind of like being on location—if you like location. Which I most certainly don’t. Niagara. That stinker. Yuk.

TC: So let’s hear about your secret lover.

Marilyn: (Silence)

TC: (Silence)

Marilyn: (Giggles)

TC: (Silence)

Marilyn: You know so many women. Who’s the most attractive woman you know?

TC: No contest. Barbara Paley. Hands down.

Marilyn (frowning): Is that the one they call “Babe”? She sure doesn’t look like any Babe to me. I’ve seen her in Vogue and all. She’s so elegant. Lovely. Just looking at her pictures makes me feel like pig-slop.

TC: She might be amused to hear that. She’s very jealous of you.

Marilyn: Jealous of me? Now there you go again, laughing.

TC: Not at all. She is jealous.

Marilyn: But why?

TC: Because one of the columnists, Kilgallen I think, ran a blind item that said something like: “Rumor hath it that Mrs. DiMaggio rendezvoused with television’s toppest tycoon and it wasn’t to discuss business.” Well, she read the item and she believes it.

Marilyn: Believes what?

TC: That her husband is having an affair with you. William S. Paley. TV’s toppest tycoon. He’s partial to shapely blondes. Brunettes, too.

Marilyn: But that’s batty. I’ve never met the guy.

TC: Ah, come on. You can level with me. This secret lover of yours—it’s William S. Paley, n’est-ce pas?

Marilyn: No! It’s a writer. He’s a writer.

TC: That’s more like it. Now we’re getting somewhere. So your lover is a writer. Must be a real hack, or you wouldn’t be ashamed to tell me his name.

Marilyn (furious, frantic): What does the “S” stand for?

TC: “S.” What “S”?

Marilyn: The “S” in William S. Paley.

TC: Oh, that “S.” It doesn’t stand for anything. He sort of tossed it in there for appearance sake.

Marilyn: It’s just an initial with no name behind it? My goodness. Mr. Paley must be a little insecure.

TC: He twitches a lot. But let’s get back to our mysterious scribe.

Marilyn: Stop it! You don’t understand. I have so much to lose.

TC: Waiter, we’ll have another Mumm’s, please.

Marilyn: Are you trying to loosen my tongue?

TC: Yes. Tell you what. We’ll make an exchange. I’ll tell you a story, and if you think it’s interesting, then perhaps we can discuss your writer friend.

Marilyn (tempted, but reluctant): What’s your story about?

TC: Errol Flynn.

Marilyn: (Silence)

TC: (Silence)

Marilyn (hating herself): Well, go on.

TC: Errol and I once spent a cozy evening together. If you follow me.

Marilyn: You’re making this up. You’re trying to trick me.

TC: Scout’s honor. I’m dealing from a clean deck. (Silence; but I can see that she’s hooked, so after lighting a cigarette…) Well, this happened when I was 18. Nineteen. It was during the war. The winter of 1943. That night Carol Marcus, or maybe she was already Carol Saroyan, was giving a party for her best friend, Gloria Vanderbilt. She gave it in her mother’s apartment on Park Avenue. Big party. About 50 people. Around midnight Errol Flynn rolls in with his alter ego, a swashbuckling playboy named Freddie McEvoy. They were both pretty loaded. Anyway, Errol started yakking with me, and he was bright, we were making each other laugh, and suddenly he said he wanted to go to El Morocco, and did I want to go with him and his buddy McEvoy. I said okay, but then McEvoy didn’t want to leave the party and all those debutantes, so in the end Errol and I left alone. Only we didn’t go to El Morocco. We took a taxi down to Gramercy Park, where I had a little one-room apartment. He stayed until noon the next day.

Marilyn: And how would you rate it? On a scale of one to ten.

TC: Frankly, if it hadn’t been Errol Flynn, I don’t think I would have remembered it.

Marilyn: That’s not much of a story. Not worth mine—not by a long shot.

TC: Waiter, where is our champagne? You’ve got two thirsty people here.

Marilyn: And it’s not as if you’d told me anything new. I’ve always known Errol zigzagged. I have a masseur, he’s practically my sister, and he was Tyrone Power’s masseur, and he told me all about the thing Errol and Ty Power had going. No, you’ll have to do better than that.

TC: You drive a hard bargain.

Marilyn: I’m listening. So let’s hear your best experience. Along those lines.

TC: The best? The most memorable? Suppose you answer the question first.

Marilyn: And I drive hard bargains! Ha! (Swallowing champagne) Joe’s not bad. He can hit home runs. If that’s all it takes, we’d still be married. I still love him, though. He’s genuine.

TC: Husbands don’t count. Not in this game.

Marilyn (nibbling nail; really thinking): Well, I met a man, a stockbroker and nothing much to look at—65, and he wears those very thick glasses. Thick as jellyfish. I can’t say what it was, but—

TC: You can stop right there. I’ve heard all about him from other girls. He’s supposed to be sensational.

Marilyn: He is. Okay, smart-ass. Your turn.

TC: Forget it. I don’t have to tell you damn nothing. Because I know who your masked marvel is: Arthur Miller. (She lowered her black glasses: Oh boy, if looks could kill, wow!) I guessed as soon as you said he was a writer.

Marilyn (stammering): But how? I mean, nobody… hardly anybody—

TC: At least three, maybe four years ago Irving Drutman—

Marilyn: Irving who?

TC: Drutman. He’s a writer on the Herald Tribune. He told me you were fooling around with Arthur Miller. Had a hang-up on him. I was too much of a gentleman to mention it before.

Marilyn: Gentleman! You bastard. (Stammering again, but dark glasses in place) You don’t understand. That was long ago. That ended. But this is new. It’s all different now, and—

TC: Just don’t forget to invite me to the wedding.

Marilyn: If you talk about this, I’ll murder you. I’ll have you bumped off. I know a couple of men who’d gladly do me the favor.

TC: I don’t question that for an instant.

(At last the waiter returned with the second bottle.)

Marilyn: Tell him to take it back. I don’t want any. I want to get the hell out of here.

TC: Sorry if I’ve upset you.

Marilyn: I’m not upset.

(But she was. While I paid the check, she left for the powder room, and I wished I had a book to read: her visits to powder rooms sometimes lasted as long as an elephant’s pregnancy. Idly, as time ticked by, I wondered if she was popping uppers or downers. Downers, no doubt. There was a newspaper on the bar, and I picked it up; it was written in Chinese. After 20 minutes had passed, I decided to investigate. Maybe she’d popped a lethal dose, or even cut her wrists. I found the ladies’ room, and knocked on the door. She said: “Come in.” Inside, she was confronting a dimly lit mirror. I said: “What are you doing?” She said: “Looking at Her.” In fact, she was coloring her lips with ruby lipstick. Also, she had removed the somber head scarf and combed out her glossy, fine-as-cotton-candy hair.)

Marilyn: I hope you have enough money left.

TC: That depends. Not enough to buy pearls, if that’s your idea of making amends.

Marilyn (giggling, returned to good spirits. I decided I wouldn’t mention Arthur Miller again): No. Only enough for a long taxi ride.

TC: Where are we going—Hollywood?

Marilyn: Hell, no. A place I like. You’ll find out when we get there.

(I didn’t have to wait that long, for as soon as we had flagged a taxi, I heard her instruct the cabby to drive to the South Street pier, and I thought: Isn’t that where one takes the ferry to Staten Island? And my next conjecture was: She’s swallowed pills on top of that champagne and now she’s off her rocker.)

TC: I hope we’re not going on any boat rides. I didn’t pack my Dramamine.

Marilyn (happy, giggling): Just the pier.

TC: May I ask why?

Marilyn: I like it there. It smells foreign, and I can feed the seagulls.

TC: With what? You haven’t anything to feed them.

Marilyn: Yes, I do. My purse is full of fortune cookies. I swiped them from that restaurant.

TC (kidding her): Uh-huh. While you were in the John I cracked one open. The slip inside was a dirty joke.

Marilyn: Gosh. Dirty fortune cookies?

TC: I’m sure the gulls won’t mind.

(Our route carried us through the Bowery. Tiny pawnshops and blood-donor stations and dormitories with 50-cent cots and tiny, grim hotels with dollar beds and bars for whites, bars for blacks, everywhere bums, bums, young, far from young, ancient, bums squatting curbside, squatting amid shattered glass and pukey debris, bums slanting in doorways and huddled like penguins at street corners. Once, when we paused for a red light, a purple-nosed scarecrow weaved toward us and began swabbing the taxi’s windshield with a wet rag clutched in a shaking hand. Our protesting driver shouted Italian obscenities.)

Marilyn: What is it? What’s happening?

TC: He wants a tip for cleaning the window.

Marilyn (shielding her face with her purse): How horrible! I can’t stand it. Give him something. Hurry. Please!

(But the taxi had already zoomed ahead, damn near knocking down the old lush. Marilyn was crying.) I’m sick.

TC: You want to go home?

Marilyn: Everything’s ruined.

TC: I’ll take you home.

Marilyn: Give me a minute. I’ll be okay.

(Thus we traveled on to South Street, and indeed the sight of a ferry moored there, with the Brooklyn skyline across the water and careening, cavorting seagulls white against a marine horizon streaked with thin fleecy clouds fragile as lace—this tableau soon soothed her soul.

(As we got out of the taxi we saw a man with a chow on a leash, a prospective passenger, walking toward the ferry, and as we passed them, my companion stopped to pat the dog’s head.)

The Man (firm, but not unfriendly): You shouldn’t touch strange dogs. Especially chows. They might bite you.

Marilyn: Dogs never bite me. Just humans. What’s his name?

The Man: Fu Manchu.

Marilyn (giggling): Oh, just like the movie. That’s cute.

The Man: What’s yours?

Marilyn: My name? Marilyn.

The Man: That’s what I thought. My wife will never believe me. Can I have your autograph?

(He produced a business card and a pen; using her purse to write on, she wrote: God Bless You—Marilyn Monroe.)

Marilyn: Thank you.

The Man: Thank you. Wait’ll I show this back at the office.

(We continued to the edge of the pier, and listened to the water sloshing against it.)

Marilyn: I used to ask for autographs. Sometimes I still do. Last year Clark Gable was sitting next to me in Chasen’s, and I asked him to sign my napkin.

(Leaning against a mooring stanchion, she presented a profile: Galatea surveying unconquered distances. Breezes fluffed her hair, and her head turned toward me with an ethereal ease, as though a breeze had swiveled it.)

TC: So when do we feed the birds? I’m hungry, too. It’s late, and we never had lunch.

Marilyn: Remember, I said if anybody ever asked you what I was like, what Marilyn Monroe was really like—well, how would you answer them? (Her tone was teaseful, mocking, yet earnest, too: she wanted an honest reply.) I bet you’d tell them I was a slob. A banana split.

TC: Of course. But I’d also say…

(The light was leaving. She seemed to fade with it, blend with the sky and clouds, recede beyond them. I wanted to lift my voice louder than the seagulls’ cries and call her back: Marilyn! Marilyn, why did everything have to turn out the way it did? Why does life have to be so rotten?)

TC: I’d say…

Marilyn: I can’t hear you.

TC: I’d say you are a beautiful child.

Walton Ford was born in New York’s asphalt jungle at the end of the 60’s. He graduated from Rhode Island School of Design with a BFA degree. Though he first inspired to be a filmmaker, Ford would soon trade his camera for brushes, palettes, canvas and any other artistic supplies for printing and painting stills taken from wildlife.

Even as a toddler he felt fascinated by fauna. His parents encouraged his love of nature by taking him on Canadian getaways and to the Museum of Natural History in New York. Thanks to frequent visits to those places, his devotion for Akeley’s dioramas grew up. Biologist and sculptor Carl Ethen Akeley is considered the father of modern taxidermy.

At first glance, Walton Ford’s stunning high definition and large scale watercolors evoke 19th century naturalistic plates made by John James Audubon, George Catlin or Edward Lear. This makes sense, as Walton drew his inspiration from them. When we stare at his pieces, a brand new world is revealed: a complex, uncanny and disturbing one, full of symbols, hidden jokes and references to operatic characteristics related to natural history representative themes.

Beasts and birds that wander around in the life-size paintings of this contemporary artist are never mere subjects, but dynamic actors that struggle in great allegorical fights. They are an extensive set of plates that subsequently were scraped together for a de-luxe limited edition of the book Pancha Tantra, released by Taschen. Pancha Tantra is a 3rd century anthology of Hindu animal tales, written in Sanskrit, centuries before La Fontaine or Aesop wrote their fables.

Watercolor techniques demand precision and Walton’s work is nothing if not precise. He stays away from unfinished or sketchy allure. Paradoxically, that kind of impressive hyperrealism that seems an impromptu note is very typical of him. It happens because he thinks nature is always unpredictable. Sometimes wild life is cruel, untamed, irrational, tender, perturbing… in other words, always multifaceted. Nature is never static, although he may paint an animal posing in fraganti.

Marginalia written with elegant old-fashioned calligraphy is an infallible element of his drawings. In these annotations he synthesizes the rest of the exposed message. It is an epilogue, a key that allows decoding the mystery around the image.

His pieces have political commentaries. He said, “I use a source that comes from the period that suits the natural history image, like this Alexander Kingslake book called Eothen, which is a beautiful book. And I try to bring it up to date and think about how it affects the way we think today and how similar the nineteenth century is to now. That moment of empire is almost the same. That moment of fear and first contact and misunderstanding and misapprehension is exactly what we’re going through right now. And we haven’t seemed to figure anything more or less out since then. You still feel like you would be carefully shot and carelessly buried if you made the wrong move.”

Besides Eothen, there are other sources of backing: Benjamin Franklin’s letters; Leonardo da Vinci’s diaries; testimonies from a zoo manager; excerpts from José Martí, Ernest Hemingway or Marquis of Sade’s books; or The Criminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals by E.P. Evans (1906). In Walton Ford’s paintings we can notice an approach to Goya, Rembrandt, Brueghel, Durer, or even Robert Crumb’s humor. Nonetheless, Walton insists that Audubon (the Haitian artist who claimed to be a Jacques Louis David pupil) is his main inspiration.

“Part of the reason I got interested in using watercolor is that I was interested in painting things that looked like Audubons. They were like fake Audubons, but I twisted the subject matter a bit, and got inside his head, and tried to paint as if it was really his tortured soul portrayed. As if his hand betrayed him, and he painted what he didn’t want to expose about himself. And it was very important to me to make them look like Audubons, to make them look like they were a hundred years old—like he painted them but that they escaped out of him. Almost like A Picture of Dorian Gray, but a natural history image.”

“And once I was sort of finished with that, I realized that I sort of did those for my own amusement. And I was doing bigger oil paintings; I was doing constructions at that time. I was doing all kinds of stuff, trying to find my way. You go through these periods in your artistic evolution where you’re trying a bunch of different things out. And that was just one of the things I was trying out at that time. And I felt like it was more successful than most of the other things I attempted to do, partly because I had all these years of drawing, since I was a little kid. So, they were more convincing, right off the bat.”

by Jade Reason

La vía del estilo

Art still has truth. Take refuge there.

Tales from Tinseltown...recording them now...I'll let you know when it's story time.

My Work My Art My Show - new school Sex and the City

All my words that are fit to print (and other's too!)

Making Life more Beautiful

Tulio Silva

Life, Leisure, Luxury

MYTHS AND HISTORIES OF A RELUCTANT BLOGGER

All my aimless thoughts, ideas, and ramblings, all packed into one site!

Meaning in Being. You be you.

Poetry, musings and sightings from where the country changes

Cooking is personalization.

Creativity is within us all