By Craig Copetas

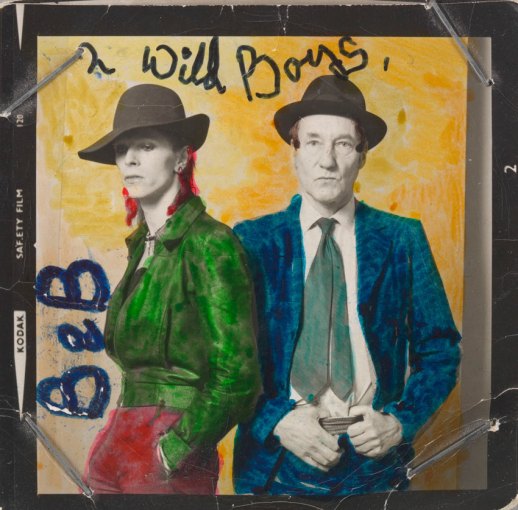

David Bowie and William S. Burroughs. Photographs by Terry O’Neill, 1974

David Bowie and William S. Burroughs. Photographs by Terry O’Neill, 1974

Terry O’Neill’s photograph hand-colored by Bowie

Terry O’Neill’s photograph hand-colored by Bowie

William Seward Burroughs is not a talkative man. Once at a dinner he gazed down into a pair of stereo microphones trained to pick up his every munch and said, “I don’t like talk and I don’t like talkers. Like Ma Barker. You remember Ma Barker? Well, that’s what she always said, ‘Ma Barker doesn’t like talk and she doesn’t like talkers.’ She just sat there with her gun.”

This was on my mind as much as the mysterious personality of David Bowie when an Irish cabbie drove Burroughs and me to Bowie’s London home on November 17th (“Strange blokes down this part o’ London, mate”). I had spent the last several weeks arranging this two-way interview. I had brought Bowie all of Burroughs’ novels: Naked Lunch, Nova Express. The Ticket That Exploded and the rest. He’d only had time to read Nova Express. Burroughs for his part had only heard two Bowie songs, Five Years and Star Man, though he had read all of Bowie’s lyrics. Still they had expressed interest in meeting each other.

Bowie’s house is decorated in a science-fiction mode: A gigantic painting, by an artist whose style fell midway between Salvador Dali and Norman Rockwell, hung over a plastic sofa. Quite a contrast to Burroughs’ humble two-room Piccadilly flat, decorated with photos of Brion Gysin – modest quarters for such a successful writer, more like the Beat Hotel in Paris than anything else.

Soon Bowie entered, wearing three-tone NASA jodhpurs. He jumped right into a detailed description of the painting and its surrealistic qualities. Burroughs nodded, and the interview/conversation began. The three of us sat in the room for two hours, talking and taking lunch: a Jamaican fish dish, prepared by a Jamaican in the Bowie entourage, with avocados stuffed with shrimp and a beaujolais nouveau, served by two interstellar Bowieites.

There was immediate liking and respect between the two. In fact, a few days after the conversation Bowie asked Burroughs for a favor: A production of The Maids staged by Lindsey Kemp, Bowie’s old mime teacher, had been closed down in London by playwright Jean Genet’s London publisher. Bowie wanted to bring the matter to Genet’s attention personally. Burroughs was impressed by Bowie’s description of the production and promised to help. A few weeks later Bowie went to Paris in search of Genet, following leads from Burroughs.

Who knows? Perhaps a collaboration has begun; perhaps, as Bowie says, they may be the Rogers and Hammerstein of the Seventies.

Burroughs: Do you do all your designs yourself?

Bowie: Yes, I have to take total control myself. I can’t let anybody else do anything, for I find that I can do things better for me. I don’t want to get other people playing with what they think that I’m trying to do. I don’t like to read things that people write about me. I’d rather read what kids have to say about me, because it’s not their profession to do that.

People look to me to see what the spirit of the Seventies is, at least 50% of them do. Critics I don’t understand. They get too intellectual. They’re not very well-versed in street talk; it takes them longer to say it. So they have to do it in dictionaries and they take longer to say it.

I went to a middle-class school, but my background is working class. I got the best of both worlds, I saw both classes, so I have a pretty fair idea of how people live and why they do it. I can’t articulate it too well, but I have a feeling about it. But not the upper class. I want to meet the Queen and then I’ll know. How do you take the picture that people paint of you?

Burroughs: They try to categorize you. They want to see their picture of you and if they don’t see their picture of you they’re very upset. Writing is seeing how close you can come to make it happen, that’s the object of all art. What else do they think man really wants, a whiskey priest on a mission he doesn’t believe in? I think the most important thing in the world is that the artists should take over this planet because they’re the only ones who can make anything happen. Why should we let these fucking newspaper politicians take over from us?

Bowie: I change my mind a lot. I usually don’t agree with what I say very much. I’m an awful liar.

Burroughs: I am too.

Bowie: I’m not sure whether it is me changing my mind, or whether I lie a lot. It’s somewhere between the two. I don’t exactly lie, I change my mind all the time. People are always throwing things at me that I’ve said and I say that I didn’t mean anything. You can’t stand still on one point for your entire life.

Burroughs: Only politicians lay down what they think and that is it. Take a man like Hitler, he never changed his mind.

Bowie: Nova Express really reminded me of Ziggy Stardust, which I am going to be putting into a theatrical performance. Forty scenes are in it and it would be nice if the characters and actors learned the scenes and we all shuffled them around in a hat the afternoon of the performance and just performed it as the scenes come out. I got this all from you, Bill… so it would change every night.

Burroughs: That’s a very good idea, visual cut-up in a different sequence.

Bowie: I get bored very quickly and that would give it some new energy. I’m rather kind of old school, thinking that when an artist does his work it’s no longer his…. I just see what people make of it. That is why the TV production of Ziggy will have to exceed people’s expectations of what they thought Ziggy was.

Burroughs: Could you explain this Ziggy Stardust image of yours? From what I can see it has to do with the world being on the eve of destruction within five years.

Bowie: The time is five years to go before the end of the earth. It has been announced that the world will end because of lack of natural resources. [The album was released three years ago.] Ziggy is in a position where all the kids have access to things that they thought they wanted. The older people have lost all touch with reality and the kids are left on their own to plunder anything. Ziggy was in a rock & roll band and the kids no longer want rock & roll. There’s no electricity to play it. Ziggy’s adviser tells him to collect news and sing it, ’cause there is no news. So Ziggy does this and there is terrible news. All the Young Dudes is a song about this news. It is no hymn to the youth as people thought. It is completely the opposite.

Burroughs: Where did this Ziggy idea come from, and this five-year idea? Of course, exhaustion of natural resources will not develop the end of the world. It will result in the collapse of civilization. And it will cut down the population by about three-quarters.

Bowie: Exactly. This does not cause the end of the world for Ziggy. The end comes when the infinites arrive. They really are a black hole, but I’ve made them people because it would be very hard to explain a black hole onstage.

Burroughs: Yes, a black hole onstage would be an incredible expense. And it would be a continuing performance, first eating up Shaftesbury Avenue.

Bowie: Ziggy is advised in a dream by the infinites to write the coming of a starman, so he writes Starman, which is the first news of hope that the people have heard. So they latch onto it immediately. The starmen that he is talking about are called the infinites, and they are black-hole jumpers. Ziggy has been talking about this amazing spaceman who will be coming down to save the earth. They arrive somewhere in Greenwich Village. They don’t have a care in the world and are of no possible use to us. They just happened to stumble into our universe by black-hole jumping. Their whole life is traveling from universe to universe. In the stage show, one of them resembles Brando, another one is a black New Yorker. I even have one called Queenie the Infinite Fox.

Now Ziggy starts to believe in all this himself and thinks himself a prophet of the future starman. He takes himself up to incredible spiritual heights and is kept alive by his disciples. When the infinites arrive, they take bits of Ziggy to make themselves real because in their original state they are anti-matter and cannot exist on our world. And they tear him to pieces onstage during the song Rock and Roll Suicide. As soon as Ziggy dies onstage the infinites take his elements and make themselves visible. It is a science-fiction fantasy of today and this is what literally blew my head off when I read Nova Express, which was written in 1961. Maybe we are the Rogers and Hammerstein of the Seventies, Bill!

Burroughs: Yes, I can believe that. The parallels are definitely there, and it sounds good.

Bowie: I must have the total image of a stage show. It has to be total with me. I’m just not content writing songs, I want to make it three-dimensional. Songwriting as an art is a bit archaic now. Just writing a song is not good enough.

Burroughs: It’s the whole performance. It’s not like somebody sitting down at the piano and just playing a piece.

Bowie: A song has to take on character, shape, body and influence people to an extent that they use it for their own devices. It must affect them not just as a song, but as a lifestyle. The rock stars have assimilated all kinds of philosophies, styles, histories, writings, and they throw out what they have gleaned from that.

Burroughs: The revolution will come from ignoring the others out of existence.

Bowie: Really. Now we have people who are making it happen on a level faster than ever. People who are into groups like Alice Cooper, the New York Dolls and Iggy Pop, who are denying totally and irrevocably the existence of people who are into the Stones and the Beatles. The gap has decreased from 20 years to ten years.

Burroughs: The escalating rate of change. The media are really responsible for most of this. Which produces an incalculable effect.

Bowie: Once upon a time, even when I was 13 or 14, for me it was between 14 and 40 that you were old. Basically. But now it is 18-year-olds and 26-year-olds – there can be incredible discrepancies, which is really quite alarming. We are not trying to bring people together, but to wonder how much longer we’ve got. It would be positively boring if minds were in tune. I’m more interested in whether the planet is going to survive.

Burroughs: Actually, the contrary is happening; people are getting further and further apart.

Bowie: The idea of getting minds together smacks of the Flower Power period to me. The coming together of people I find obscene as a principle. It is not human. It is not a natural thing as some people would have us believe.

Copetas: What about love?

Burroughs: Ugh.

Bowie: I’m not at ease with the word “love.”

Burroughs: I’m not either.

Bowie: I was told that it was cool to fall in love, and that period was nothing like that to me. I gave too much of my time and energy to another person and they did the same to me and we started burning out against each other. And that is what is termed love… that we decide to put all our values on another person. It’s like two pedestals, each wanting to be the other pedestal.

Burroughs: I don’t think that “love” is a useful word. It is predicated on a separation of a thing called sex and a thing called love and that they are separate. Like the primitive expressions in the old South when the woman is on a pedestal, and the man worshipped his wife and then went out and fucked a whore. It is primarily a Western concept and then it extended to the whole Flower Power thing of loving everybody. Well, you can’t do that because the interests are not the same.

Bowie: The word is wrong, I’m sure. It is the way you understand love. The love that you see, among people who say, “We’re in love,” it’s nice to look at… but wanting not to be alone, wanting to have a person there that they relate to for a few years is not often the love that carries on throughout the lives of those people. There is another word. I’m not sure whether it is a word. Love is every type of relationship that you think of… I’m sure it means relationship, every type of relationship that you can think of.

Copetas: What of sexuality, where is it going?

Bowie: Sexuality and where it is going is an extraordinary question, for I don’t see it going anywhere. It is with me, and that’s it. It’s not coming out as a new advertising campaign next year. It’s just there. Everything you can think about sexuality is just there. Maybe there are different kinds of sexuality, maybe they’ll be brought into play more. Like one time it was impossible to be homosexual as far as the public were concerned. Now it is accepted. Sexuality will never change, for people have been fucking their own particular ways since time began and will continue to do it. Just more of those ways will be coming to light. It might even reach a puritan state.

Burroughs: There are certain indications that it might be going that way in the future, real backlash.

Bowie: Oh yes, look at the rock business. Poor old Clive Davis. He was found to be absconding with money and there were also drug things tied up with it. And that has started a whole clean-up campaign among record companies; they’re starting to ditch some of their artists.

I’m regarded quite asexually by a lot of people. And the people that understand me the best are nearer to what I understand about me. Which is not very much, for I’m still searching. I don’t know, the people who are coming anywhere close to where I think I’m at regard me more as an erogenous kind of thing. But the people who don’t know so much about me regard me more sexually.

But there again, maybe it’s the disinterest with sex after a certain age, because the people who do kind of get nearer to me are generally older. And the ones who regard me as more of a sexual thing are generally younger. The younger people get into the lyrics in a different way; there’s much more of a tactile understanding, which is the way I prefer it. ‘Cause that’s the way I get off on writing, especially William’s. I can’t say that I analyze it all and that’s exactly what you’re saying, but from a feeling way I got what you meant. It’s there, a whole wonderhouse of strange shapes and colors, tastes, feelings.

I must confess that up until now I haven’t been an avid reader of William’s work. I really did not get past Kerouac to be honest. But when I started looking at your work I really couldn’t believe it. Especially after reading Nova Express. I really related to that. My ego obviously put me on to the Pay Color chapter, then I started dragging out lines from the rest of the book.

Burroughs: Your lyrics are quite perceptive.

Bowie: They’re a bit middle class, but that’s all right, ’cause I’m middle class.

Burroughs: It is rather surprising that they are such complicated lyrics, that can go down with a mass audience. The content of most pop lyrics is practically zero, like Power to the People.

Bowie: I’m quite certain that the audience that I’ve got for my stuff don’t listen to the lyrics.

Burroughs: That’s what I’m interested in hearing about… do they understand them?

Bowie: Well, it comes over more as a media thing and it’s only after they sit down and bother to look. On what level they are reading them, they do understand them, because they will send me back their own kind of write-ups of what I’m talking about, which is great for me because sometimes I don’t know. There have been times when I’ve written something and it goes out and it comes back in a letter from some kid as to what they think about it and I’ve taken their analysis to heart so much that I have taken up his thing. Writing what my audience is telling me to write.

Lou Reed is the most important definitive writer in modern rock. Not because of the stuff that he does, but the direction that he will take it. Half the new bands would not be around if it were not for Lou. The movement that Lou’s stuff has created is amazing. New York City is Lou Reed. Lou writes in the street-gut level and the English tend to intellectualize more.

Burroughs: What is your inspiration for writing, is it literary?

Bowie: I don’t think so.

Burroughs: Well, I read this eight-line poem of yours and it is very reminiscent of T.S. Eliot.

Bowie: Never read him.

Burroughs: [Laughs] It is very reminiscent of Waste Land. Do you get any of your ideas from dreams?

Bowie: Frequently.

Burroughs: I get 70% of mine from dreams.

Bowie: There’s a thing that just as you go to sleep, if you keep your elbows elevated that you will never go below the dream stage. And I’ve used that quite a lot and it keeps me dreaming much longer than if I just relaxed.

Burroughs: I dream a great deal, and then because I am a light sleeper, I will wake up and jot down just a few words and they will always bring the whole idea back to me.

Bowie: I keep a tape recorder by the bed and then if anything comes I just say it into the tape recorder. As for my inspiration, I haven’t changed my views much since I was about 12, really, I’ve just got a 12-year-old mentality. When I was in school I had a brother who was into Kerouac and he gave me On The Road to read when I was 12 years old. That’s still been a big influence.

Copetas: The images both of you transpire are very graphic, almost comic-booky in nature.

Bowie: Well, yes, I find it easier to write in these little vignettes; if I try to get any more heavy, I find myself out of my league. I couldn’t contain myself in what I say. Besides if you are really heavier there isn’t that much more time to read that much, or listen to that much. There’s not much point in getting any heavier… there’s too many things to read and look at. If people read three hours of what you’ve done, then they’ll analyze it for seven hours and come out with seven hours of their own thinking… where if you give them 30 seconds of your own stuff they usually still come out with seven hours of their own thinking. They take hook images of what you do. And they pontificate on the hooks. The sense of the immediacy of the image. Things have to hit for the moment. That’s one of the reasons I’m into video; the image has to hit immediately. I adore video and the whole cutting up of it.

What are your projects at the moment?

Burroughs: At the moment I’m trying to set up an institute of advanced studies somewhere in Scotland. Its aim will be to extend awareness and alter consciousness in the direction of greater range, flexibility and effectiveness at a time when traditional disciplines have failed to come up with viable solutions. You see, the advent of the space age and the possibility of exploring galaxies and contacting alien life forms poses an urgent necessity for radically new solutions. We will be considering only non-chemical methods with the emphasis placed on combination, synthesis, interaction and rotation of methods now being used in the East and West, together with methods that are not at present being used to extend awareness or increase human potentials.

We know exactly what we intend to do and how to go about doing it. As I said, no drug experiments are planned and no drugs other than alcohol, tobacco and personal medications obtained on prescription will be permitted in the center. Basically, the experiments we propose are inexpensive and easy to carry out. Things such as yoga-style meditation and exercises, communication, sound, light and film experiments, experiments with sensory deprivation chambers, pyramids, psychotronic generators and Reich’s orgone accumulators, experiments with infra-sound, experiments with dream and sleep.

Bowie: That sounds fascinating. Are you basically interested in energy forces?

Burroughs: Expansion of awareness, eventually leading to mutations. Did you read Journey Out of the Body? Not the usual book on astral projection. This American businessman found he was having these experiences of getting out of the body – never used any hallucinogenic drugs. He’s now setting up this astral air force. This psychic thing is really a rave in the States now. Did you experience it much when you were there?

Bowie: No, I really hid from it purposely. I was studying Tibetan Buddhism when I was quite young, again influenced by Kerouac. The Tibetan Buddhist Institute was available so I trotted down there to have a look. Lo and behold there’s a guy down in the basement who’s the head man in setting up a place in Scotland for the refugees, and I got involved purely on a sociological level – because I wanted to help get the refugees out of India, for they were really having a shitty time of it down there, dropping like flies due to the change of atmosphere from the Himalayas.

Scotland was a pretty good place to put them, and then more and more I was drawn to their way of thinking, or non thinking, and for a while got quite heavily involved in it. I got to the point where I wanted to become a novice monk and about two weeks before I was actually going to take those steps, I broke up and went out on the streets and got drunk and never looked back.

Burroughs: Just like Kerouac.

Bowie: Go to the States much?

Burroughs: Not since ’71.

Bowie: It has changed, I can tell you, since then.

Burroughs: When were you last back?

Bowie: About a year ago.

Burroughs: Did you see any of the porn films in New York?

Bowie: Yes, quite a few.

Burroughs: When I was last back, I saw about 30 of them. I was going to be a judge at the erotic film festival.

Bowie: The best ones were the German ones; they were really incredible.

Burroughs: I thought that the American ones were still the best. I really like film…. I understand that you may play Valentine Michael Smith in the film version of Stranger in a Strange Land.

Bowie: No, I don’t like the book much. In fact, I think it is terrible. It was suggested to me that I make it into a movie, then I got around to reading it. It seemed a bit too Flower-Powery and that made me a bit wary.

Burroughs: I’m not that happy with the book either. You know, science fiction has not been very successful. It was supposed to start a whole new trend and nothing happened. For the special effects in some of the movies, like 2001, it was great. But it all ended there.

Bowie: I feel the same way. Now I’m doing Orwell’s 1984 on television; that’s a political thesis and an impression of the way in another country. Something of that nature will have more impact on television. I don’t believe in proper cinema; it doesn’t have the strength of television. People having to go out to the cinema is really archaic. I’d much rather sit at home.

Burroughs: Do you mean the whole concept of the audience?

Bowie: Yes, it is ancient. No sense of immediacy.

Burroughs: Exactly, it all relates back to image and the way in which it is used.

Bowie: Right. I’d like to start a TV station.

Burroughs: There are hardly any programs worth anything any more. The British TV is a little better than American. The best thing the British do is natural history. There was one last week with sea lions eating penguins, incredible. There is no reason for dull programs, people get very bored with housing projects and coal strikes.

Bowie: They all have an interest level of about three seconds. Enough time to get into the commentator’s next sentence. And that is the premise it works on. I’m going to put together all the bands that I think are of great value in the States and England, then make an hour-long program about them. Probably a majority of people have never heard of these bands. They are doing and saying things in a way other bands aren’t. Things like the Puerto Rican music at the Cheetah Club in New York. I want people to hear musicians like Joe Cuba. He has done things to whole masses of Puerto Rican people. The music is fantastic and important. I also want to start getting Andy Warhol films on TV.

Burroughs: Have you ever met Warhol?

Bowie: Yes, about two years ago I was invited up to The Factory. We got in the lift and went up and when it opened there was a brick wall in front of us. We rapped on the wall and they didn’t believe who we were. So we went back down and back up again till finally they opened the wall and everybody was peering around at each other. That was shortly after the gun incident. I met this man who was the living dead. Yellow in complexion, a wig on that was the wrong color, little glasses. I extended my hand and the guy retired, so I thought, “The guy doesn’t like flesh, obviously he’s reptilian.” He produced a camera and took a picture of me. And I tried to make small talk with him, and it wasn’t getting anywhere.

But then he saw my shoes. I was wearing a pair of gold-and-yellow shoes, and he says, “I adore those shoes, tell me where you got those shoes.” He then started a whole rap about shoe design and that broke the ice. My yellow shoes broke the ice with Andy Warhol.

I adore what he was doing. I think his importance was very heavy, it’s become a big thing to like him now. But Warhol wanted to be cliche, he wanted to be available in Woolworth’s, and be talked about in that glib type of manner. I hear he wants to make real films now which is very sad because the films he was making were the things that should be happening. I left knowing as little about him as a person as when I went in.

Burroughs: I don’t think that there is any person there. It’s a very alien thing, completely and totally unemotional. He’s really a science-fiction character. He’s got a strange green color.

Bowie: That’s what struck me. He’s the wrong color, this man is the wrong color to be a human being. Especially under the stark neon lighting that is in The Factory. Apparently it is a real experience to behold him in the daylight.

Burroughs: I’ve seen him in all light and still have no idea as to what is going on, except that it is something quite purposeful. It’s not energetic, but quite insidious, completely asexual. His films will be the late-night movies of the future.

Bowie: Exactly. Remember Pork? I want to get that onto TV. TV has eaten up everything else, and Warhol films are all that are left, which is fabulous. Pork could become the next I Love Lucy, the great American domestic comedy. It’s about how people really live, not like Lucy, who never touched dishwater. It’s about people living and hustling to survive.

That’s what Pork is all about. A smashing of the spectacle. Although I’d like to do my own version of Sindbad The Sailor. I think that is an all-time classic. But it would have to be done on an extraordinary level. It would be incredibly indulgent and expensive. It would have to utilize lasers and all the things that are going to happen in a true fantasy.

Even the use of holograms. Holograms are important. Videotape is next, then it will be holograms. Holograms will come into use in about seven years. Libraries of video cassettes should be developed to their fullest during the interim. You can’t video enough good material from your own TV. I want to have my own choice of programs. There has to be the necessary software available.

Burroughs: I audio-record everything I can.

Bowie: The media is either our salvation or our death. I’d like to think it’s our salvation. My particular thing is discovering what can be done with media and how it can be used. You can’t draw people together like one big huge family, people don’t want that. They want isolation or a tribal thing. A group of 18 kids would much rather stick together and hate the next 18 kids down the block. You are not going to get two or three blocks joining up and loving each other. There are just too many people.

Burroughs: Too many people. We’re in an overpopulated situation, but the less people you have does not include the fact that they are still heterogeneous. They are just not the same. All this talk about a world family is a lot of bunk. It worked with the Chinese because they are very similar.

Bowie: And now one man in four in China has a bicycle and that is pretty heavy considering what they didn’t have before. And that’s the miracle as far as they’re concerned. It’s like all of us having a jet plane over here.

Burroughs: It’s because they are the personification of one character that they can live together without any friction. We quite evidently are not.

Bowie: It is why they don’t need rock & roll. British rock & roll stars played in China, played a dirty great field and they were treated like a sideshow. Old women, young children, some teenagers, you name it, everybody came along, walked past them and looked at them on the stand. It didn’t mean a thing. Certain countries don’t need rock & roll because they were so drawn together as a family unit. China has its mother-father figure – I’ve never made my mind up which – it fluctuates between the two. For the West, Jagger is most certainly a mother figure and he’s a mother hen to the whole thing. He’s not a cockadoodledoo; he’s much more like a brothel keeper or a madame.

Burroughs: Oh, very much so.

Bowie: He’s incredibly sexy and very virile. I also find him incredibly motherly and maternal clutched into his bosom of ethnic blues. He’s a white boy from Dagenham trying his damnedest to be ethnic. You see, trying to tart the rock business up a bit is getting nearer to what the kids themselves are like, because what I find, if you want to talk in the terms of rock, a lot depends on sensationalism and the kids are a lot more sensational than the stars themselves. The rock business is a pale shadow of what the kids lives are usually like. The admiration comes from the other side. It’s all a reversal, especially in recent years. Walk down Christopher Street and then you wonder exactly what went wrong. People are not like James Taylor; they may be molded on the outside, but inside their heads it is something completely different.

Burroughs: Politics of sound.

Bowie: Yes. We have kind of got that now. It has very loosely shaped itself into the politics of sound. The fact that you can now subdivide rock into different categories was something that you couldn’t do ten years ago. But now I can reel off at least ten sounds that represent a kind of person rather than a type of music. The critics don’t like to say that, because critics like being critics, and most of them wish they were rock & roll stars. But when they classify they are talking about people not music. It’s a whole political thing.

Burroughs: Like infrasound, the sound below the level of hearing. Below 16 Mertz. Turned up full blast it can knock down walls for 30 miles. You can walk into the French patent office and buy the patent for 40p. The machine itself can be made very cheaply from things you could find in a junk yard.

Bowie: Like black noise. I wonder if there is a sound that can put things back together. There was a band experimenting with stuff like that; they reckon they could make a whole audience shake.

Burroughs: They have riot-control noise based on these soundwaves now. But you could have music with infrasound, you wouldn’t necessarily have to kill the audience.

Bowie: Just maim them.

Burroughs: The weapon of the Wild Boys is a bowie knife, an 18-inch bowie knife, did you know that?

Bowie: An 18-inch bowie knife … you don’t do things by halves, do you. No, I didn’t know that was their weapon. The name Bowie just appealed to me when I was younger. I was into a kind of heavy philosophy thing when I was 16 years old, and I wanted a truism about cutting through the lies and all that.

Burroughs: Well, it cuts both ways, you know, double-edged on the end.

Bowie: I didn’t see it cutting both ways till now.

This story is from the February 28th, 1974 issue of Rolling Stone.