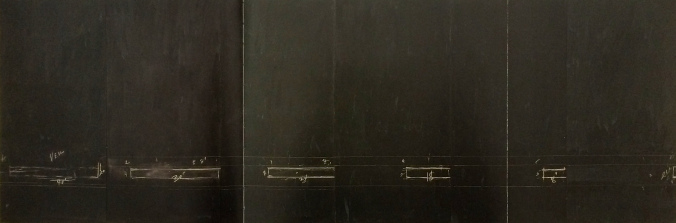

Heriodade, Cy Twombly, 1960

Heriodade, Cy Twombly, 1960

Herodiade takes its title from Mallarmé’s dramatic poem and includes direct quotations from the poem transcribed onto the canvas.

I. ANCIENT OVERTURE OF HÉRODIADE

The Nurse

(Incantation)

Abolished, and her frightful wing in the tears

Of the basin, abolished, that mirrors forth our fears,

The naked golds lashing the crimson space,

An Aurora—heraldic plumage—has chosen to embrace

Our cinerary tower of sacrifice,

Heavy tomb that a songbird has fled, lone caprice

Of a dawn vainly decked out in ebony plumes…

Ah, mansion this sad, fallen country assumes!

No splashing! the gloomy water, standing still,

No longer visited by snowy quill

Or fabled swan, reflects the bereaving

Of autumn extinguished by its own unleaving,

Of the swan when amidst the cold white tomb

Of its feathers, it buried its head, undone

By the pure diamond of a star, but one

Of long ago, which never even shone.

Crime! torture! ancient dawn! bright pyre!

Empurpled sky, complicit in the mire,

And stained-glass windows opening red on carnage.

The strange chamber, framed in all the baggage

Of a warlike age, its goldwork dull and faint,

Has yesteryear’s snows instead of its ancient tint;

And its pearl-gray tapestry, useless creases

With the buried eyes of prophetesses

Offering Magi withered fingers. One,

With floral past enwoven on my gown

Bleached in an ivory chest and with a sky

Bestrewn with birds amidst the embroidery

Of tarnished silver, seems a phantom risen,

An aroma, roses, rising from the hidden

Couch, now void, the snuffed-out candle shrouds,

An aroma, over the sachet, of frozen golds,

A drift of flowers unfaithful to the moon

(Though the taper’s quenched, petals still fall from one),

Flowers whose long regrets and stems appear

Drenched in a lonely vase to languish there…

An Aurora dragged her wings in the basin’s tears!

Magical shadow with symbolic powers!

A voice from the distant past, an evocation,

Is it not mine prepared for incantation?

In the yellow folds of thought, still unexhumed,

Lingering, and like an antique cloth perfumed,

Spread on a pile of monstrances grown cold,

Through ancient hollows and through stiffened folds

Pierced in the rhythm of the pure lace shroud

Through which the old veiled brightness is allowed

To mount, in desperation, shall arise

(But oh, the distance hidden in those cries!)

The old veiled brightness of a strange gilt-silver,

Of the languishing voice, estranged and unfamiliar:

Will it scatter its gold in an ultimate splendor,

And, in the hour of its agony, render

Itself as the anthem for psalms of petition?

For all are alike in being brought to perdition

By the power of old silence and deepening gloom,

Fated, monotonous, vanquished, undone,

Like the sluggish waters of an ancient pond.

Sometimes she sang an incoherent song.

Lamentable sign!

the bed of vellum sheets,

Useless and closed–not linen!—vainly waits,

Bereft now of the cherished grammary

That spelled the figured folds of reverie,

The silken tent that harbored memory,

The fragrance of sleeping hair. Were these its treasure?

Cold child, she held within her subtle pleasure,

Shivering with flowers in her walks at dawn,

Or when the pomegranate’s flesh is torn

By wicked night! Alone, the crescent moon

On the iron clockface is a pendulum

Suspending Lucifer: the clepsydra pours

Dark drops in grief upon the stricken hours

As, wounded, each one wanders a dim shade

On undeciphered paths without a guide!

All this the king knows not, whose salary

Has fed so long this agèd breast now dry.

Her father knows it no more than the cruel

Glacier mirroring his arms of steel,

When sprawled on a pile of corpses without coffins

Smelling obscurely of resin, he deafens

With dark silver trumpets the ancient pines!

Will he ever come back from the Cisalpines?

Soon enough! for all is bad dream and foreboding!

On the fingernail raised in the stained glass, according

To the memory of the trumpets, the old sky burns,

And to an envious candle it turns

A finger. And soon, when the sad sun sinks,

It shall pierce through the body of wax till it shrinks!

No sunset, but the red awakening

Of the last day concluding everything

Struggles so sadly that time disappears,

The redness of apocalypse, whose tears

Fall on the child, exiled to her own proud

Heart, as the swan makes its plumage a shroud

For its eyes, the old swan, and is carried away

From the plumage of grief to the eternal highway

Of its hopes, where it looks on the diamonds divine

Of a moribund star, which never more shall shine!

Stepháne Mallarmé

The poem Hérodiade was in fact never completed, but there is little doubt that the scene between Herodias and her nurse (the only part published under Mallarmé’s supervision) dates from 1864 to 1865. The heroine of Hérodiade is the biblical character more generally known as Salome, but Mallarmé may have preferred the alternative name so as to emphasize that he was concerned not with the sensuous dancer of popular legend but with an ascetic figure who is repelled by the slightest contact with the sensual world, and who, in the later, uncompleted stages of the play, was to demand the head of John the Baptist because he had inadvertently caught a glimpse of her naked body.

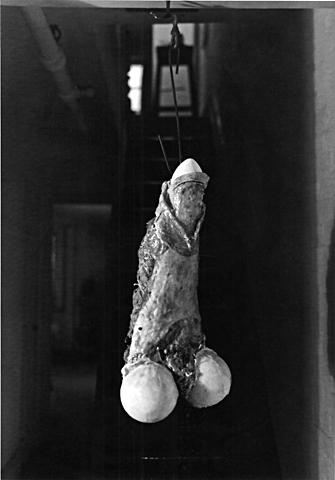

Melencholia I, Albrecht Dürer, 1514

Melencholia I, Albrecht Dürer, 1514