Zantedeschia albomaculata, from L’Illustration Horticole v.7 (1860), by Charles Antoine Lemaire (1801-1871), and Ambroise Verschaffelt (1825-1886)

Zantedeschia albomaculata, from L’Illustration Horticole v.7 (1860), by Charles Antoine Lemaire (1801-1871), and Ambroise Verschaffelt (1825-1886)

Zantedeschia is a genus of eight species of herbaceous perennial flowering plants in the family Araceae, native to southern Africa from South Africa north to Malawi. The genus has been introduced on all continents except Antarctica. Common names include arum lily for Z. aethiopica, calla, and calla lily for Z. elliottiana and Z. rehmannii although it is neither a true lily (Liliaceae), nor an Arum or a Calla (related genera in Araceae). The colourful flowers and leaves are highly valued, and both species and cultivars are widely used as ornamental plants.

The name of the calla lily is not only just a common name that never is used professionally, it is also totally misinformative since the calla lily is neither a calla nor a lily. Once it was considered to be a calla and the discoverer, famous Swedish botanist Carolus Linnaeus, actually categorized all similar plants under the calla genus. When further testing proved that not all callas were not closely related enough to be considered as one genus it was split up by the German botanist Karl Koch and the calla lily genus became known as the zantedeschia genus. The name of the genus was given as a tribute to Italian botanist Giovanni Zantedeschi (1773–1846) by the German botanist Kurt Sprengel (1766–1833).

Zantedeschia is monoecious in which separate male (staminate) and female (pistillate) flowers (imperfect or unisexual flowers) are carried on the spadix. The flowers are small and non-blooming with an absent perianth. The male flowers contain two to three stamens fused to form a synandrium, and the female flowers have a single compound pistil with three fused carpels and three locules. Zantedeschia shares the general properties of the Araceae family in causing contact irritation. Zantedeschia species are also poisonous due to the presence of calcium oxalate crystals in the form of raphides.

It is not really clear when this genus showed up in Europe, but based on an illustration from the Royal Garden in Paris in 1664, it is safe to say that it was grown in Europe at that time. Zantedeschia became a very popular flower after that, showing up at funerals, weddings and practically any festivity in Europe. It was especially popular since it could be made to bloom all year around in the southern to centre parts of Europe using simple greenhouses. It was a flower that could be grown even when the sky seemed dark.

Zantedeschia or Calla lily is a very beautiful flower. During the flower language boom in the Victorian period of the 19th century, there were strict social codes and if one had to express ones feelings, flowers were the best medium. Flowers delivered the feelings subtly and every part of gifting a flower, carried secret flower meanings. The person who made the offer to the way the flowers were arranged, all had a specific meaning. Thus passionate messages were delivered to the recipient, without the use of words through flowers. During this time, calla lily was used to express many such hidden symbols. Calla lily due to its physical resemblance to female genitalia was called an overtly sexual one. This sexual calla lily meaning was brought forward to admirers by Sigmund Freud and it was the favorite subject of artists like Diego Rivera and Georgia O’Keeffe.

Callas, Imogen Cunningham, 1925

Callas, Imogen Cunningham, 1925

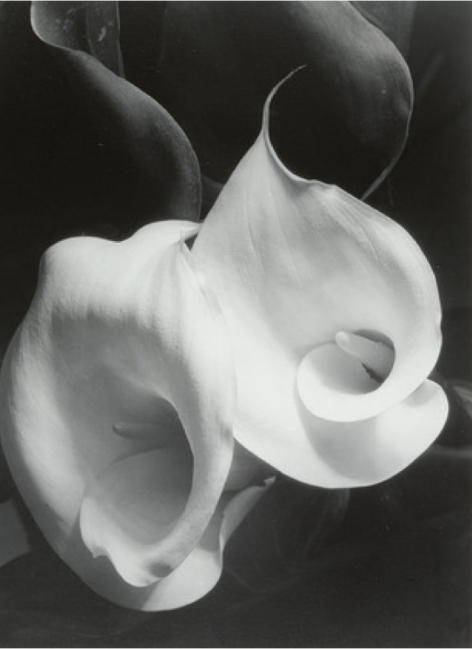

Two Callas, Imogen Cunningham, c. 1926

Two Callas, Imogen Cunningham, c. 1926

Black and White Lilies, Imogen Cunningham, 1928

Black and White Lilies, Imogen Cunningham, 1928

Calla Lily with Roses,Georgia O’Keeffe, 1926

Calla Lily with Roses,Georgia O’Keeffe, 1926

White Calla Lilly, Georgia O’Keeffe, 1927

White Calla Lilly, Georgia O’Keeffe, 1927

Two Calla Lilies on Pink, Georgia O’Keeffe, 1928

Two Calla Lilies on Pink, Georgia O’Keeffe, 1928

Caricature of Georgia O’Keeffe as “The Lady of the Lily”, Miguel Covarrubias, 1929

Caricature of Georgia O’Keeffe as “The Lady of the Lily”, Miguel Covarrubias, 1929

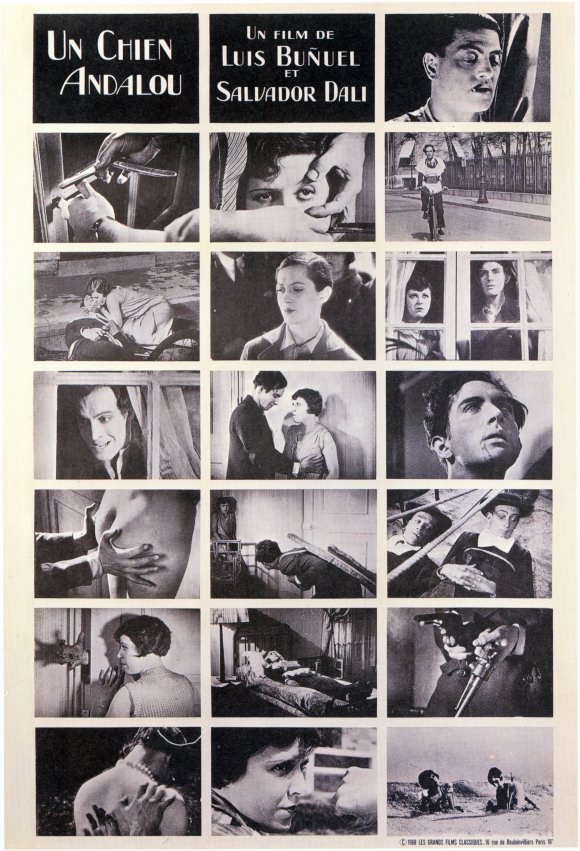

The Great Masturbator, Salvador Dalí, (1929)

The Great Masturbator, Salvador Dalí, (1929)

Flower Vendor (Girl with Lilies), Diego Rivera, 1941

Flower Vendor (Girl with Lilies), Diego Rivera, 1941

Portrait of Natasha Gelman, Diego Rivera, 1943

Portrait of Natasha Gelman, Diego Rivera, 1943

Nude with Calla Lillies, Diego Rivera, 1944

Nude with Calla Lillies, Diego Rivera, 1944

The Flower Carrier, Diego Rivera, 1953

The Flower Carrier, Diego Rivera, 1953