Originally published on February 11, 2013

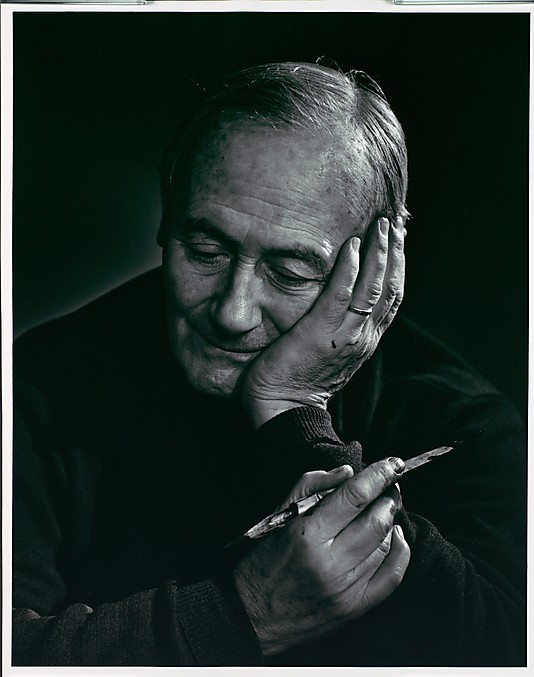

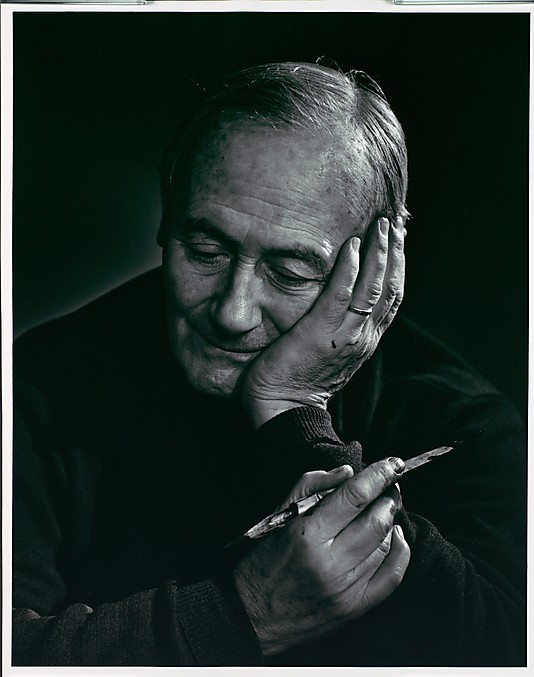

Self-Portrait. Yousuf Karsh (1908-2002)

Self-Portrait. Yousuf Karsh (1908-2002)

“On the stormy New Year’s Eve of 1925, the liner Versailles reached Halifax from Beirut. After a voyage of twenty-nine days, her most excited passenger in the steerage class must have been a seventeen-year-old Armenian boy who spoke little French, and less English. I was that boy.

My first glimpse of the New World on a steely cold, sunny winter day was the Halifax wharf, covered with snow. I could not yet begin to imagine the infinite promise of this new land. For the moment, it was enough to find myself safe, the massacres, torture, and heartbreak of Armenia behind me. I had no money and little schooling, but I had an uncle, my mother’s brother, who was waiting for me and recognized me from a crude family snapshot as I stepped from the gangplank. George Nakash, whom I had not seen before, sponsored me as an immigrant, guaranteed that I would not be a “public charge,” and traveled all the way from his home in Sherbrooke, Quebec, for our meeting — the first of his many great kindnesses.

We went up from the dock to the station in a taxi, the likes of which I had never seen — a sleigh-taxi drawn by horses. The bells on their harnesses never stopped jingling; the bells of the city rang joyously to mark a new year. The sparkling decorations on the windows of shops and houses, the laughing crowds — for me it was an unbelievable fantasy come true. On the two-day journey to my uncle’s home, I marveled at the vast distances. The train stalled in a deep snowdrift; we ran out of food; this situation, at least, was no novelty for me.

I was born in Mardin, Armenia, on December 23, 1908, of Armenian parents. My father could neither read nor write, but had exquisite taste. He traveled to distant lands to buy and sell rare and beautiful things — furniture, rugs, spices. My mother was an educated woman, a rarity in those days, and was extremely well read, particularly in her beloved Bible. Of their three living children, I was the eldest. My brothers Malak and Jamil, today in Canada and the United States, were born in Armenia. My youngest brother, Salim, born later in Aleppo, Syria, alone escaped the persecution soon to reach its climax in our birthplace.

It was the bitterest of ironies that Mardin, whose tiers of rising buildings were said to resemble the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, and whose succulent fruits convinced its inhabitants it was the original Garden of Eden, should have been the scene of the Turkish atrocities against the Armenians in 1915. Cruelty and torture were everywhere; nevertheless, life had to go on — albeit fearfully — all the while. Ruthless and hideous persecution and illness form part of my earliest memories: taking food parcels to two beloved uncles torn from their homes, cast into prison for no reason, and later thrown alive into a well to perish; the severe typhus epidemic in which my sister died, in spite of my mother’s gentle nursing. My recollections of those days comprise a strange mixture of blood and beauty, of persecution and peace.

I remember finding brief solace in my young cousin relating her Thousand and One Nights tales of fantastic ships and voyages and faraway people, and always, solace in the example of my mother, who taught me not to hate, even as the oppression continued.

One day, I returned from school, my forehead bleeding. I had been stoned by Turkish boys who tried to take away my only playthings, a few marbles. “Wait,” I told my mother defiantly, “from now on I am the one who will carry stones.” My mother took me in her arms and said, “My son, they do not know what they are doing. However, if you must retaliate — be sure you miss!”

My mother’s generosity, strength, and hope sustained our family. She took into our home a young Armenian girl, shared our few morsels of food with her, and encouraged her to use her hands instead of her eyes, which had been cruelly mutilated. My mother herself seemed tireless. She had to go every day to the distant mountain spring which was the one source of water for the whole community. Allowed only one small pail, she would wait patiently in line for hours to get enough water for her children. Running water, to me, is still a great blessing.

In 1922, our family was allowed to flee. We had to leave our doors open — with us we took no baggage, only our lives. And we had to flee on foot. During our month-long journey with a Bedouin and Kurdish caravan, which would have taken only two days by the forbidden train, my parents lost every valuable they had managed to save. My father’s last silver coin went to rescue me after I was caught foolishly making a sketch of piled-up human bones and skulls, the last bitter landmark of my country.

In the safety of Aleppo, Syria, my father painstakingly tried to rebuild our lives. Only those who have seen their savings and possessions of a lifetime destroyed can understand how great were the spiritual resources upon which my father must have drawn. Despite the continual struggle, day after day, he somehow found the means to send me to my Uncle Nakash, and to a continent then to me no more than a vague space on a schoolboy’s map.

Uncle Nakash was a photographer of established reputation, still a bachelor when I went to live with him, and a man of generous heart. If my first day at Sherbrooke High School proved a dilemma for the teachers—in what grade did one place a seventeen-year-old Armenian boy who spoke no English, who wanted to be a doctor, and who came armed only with good manners? — the school was for me a haven where I found my first friends. They not only played with me instead of stoning me, but allowed me to keep the marbles I had won. My formal education was over almost before it began, but the warmth of my reception made me love my adopted land.

I roamed the fields and woods around Sherbrooke every weekend with a small camera, one of my uncle’s many gifts. I developed the pictures myself and showed them to him for criticism. I am sure they had no merit, but I was learning, and Uncle Nakash was a valuable and patient critic.

It was with this camera that I scored my first photographic success. I photographed a landscape with children playing and gave it to a classmate as a Christmas gift. Secretly, he entered it in a contest. To my amazement, it won first prize, the then munificent sum of fifty dollars. I gave ten dollars to my friend and happily sent the rest to my parents in Aleppo, the first money I could send to them.

Shortly afterward my uncle arranged my apprenticeship with his friend John H. Garo of Boston, a fellow Armenian, who was recognized as the outstanding portraitist in the eastern states. Garo was a wise counselor; he encouraged me to attend evening classes in art and to study the work of the great masters, especially Rembrandt and Velázquez. Although I never learned to paint, or to make even a fair drawing, I learned about lighting, design, and composition. At the Public Library, which was my other home in Boston, I became a voracious reader in the humanities and began to appreciate the greater dimensions of photography.

My interest lay in the personalities that influenced all our lives, rather than merely in portraiture. Fostered by Garo’s teachings, I was yearning for adventure, to express myself, to experiment in photography. With all my possessions packed in two suitcases, I moved to Ottawa. In the capital of Canada, a crossroads of world travel, I hoped I would have the opportunity to photograph its leading figures and many foreign international visitors.

My life had been enriched by meeting many remarkable personalities on this photographic odyssey, the first of many, to record those men and women who leave their mark on our era. It would set a pattern of working away from my studio. Any room in the world where I could set up my portable lights and camera—from Buckingham Palace to a Zulu kraal, from miniature Zen Buddhist temples in Japan to the splendid Renaissance chambers of the Vatican — would become my studio.”

Tennessee Williams

Tennessee Williams

Wystan Hugh Auden

Wystan Hugh Auden

Albert Camus

Albert Camus

Sir George Bernard Shaw

Sir George Bernard Shaw

Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Hemingway

Vladimir Nabokov

Vladimir Nabokov

Sir John Buchan, Governor of Canada

Sir John Buchan, Governor of Canada

Jacques Cousteau

Jacques Cousteau

Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr.

Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali

Nelson Mandela

Nelson Mandela

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein

Jackie & John Fitzgerald Kennedy

Jackie & John Fitzgerald Kennedy

Queen Elizabeth II & Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh

Queen Elizabeth II & Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh

Rainier III Grimaldi, Prince of Monaco & Princess Grace Kelly

Rainier III Grimaldi, Prince of Monaco & Princess Grace Kelly

Audrey Hepburn & Mel Ferrer

Audrey Hepburn & Mel Ferrer

Humphrey Bogart

Humphrey Bogart

Lauren Bacall

Lauren Bacall

Audrey Hepburn

Audrey Hepburn

Grace Kelly

Grace Kelly

Anita Ekberg

Anita Ekberg

Ana Magnani

Ana Magnani

Brigitte Bardot

Brigitte Bardot

Jacqueline Lee Bouvier

Jacqueline Lee Bouvier

Elizabeth Taylor

Elizabeth Taylor

Joan Crawford

Joan Crawford

Sophia Loren with her son Edoardo

Sophia Loren with her son Edoardo

Martha Graham

Martha Graham

Alberto Giacometti

Alberto Giacometti

Max Ernst

Max Ernst

Alexander Calder

Alexander Calder

Isamu Noguchi

Isamu Noguchi

Josef Albers

Josef Albers

Henry Moore

Henry Moore

Man Ray

Man Ray

Joan Miró

Joan Miró

Andy Warhol

Andy Warhol

Georgia O´Keeffe

Georgia O´Keeffe

Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso

Norman Rockwell

Norman Rockwell

Walt Disney

Walt Disney

Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright

Mies van der Rohe

Mies van der Rohe

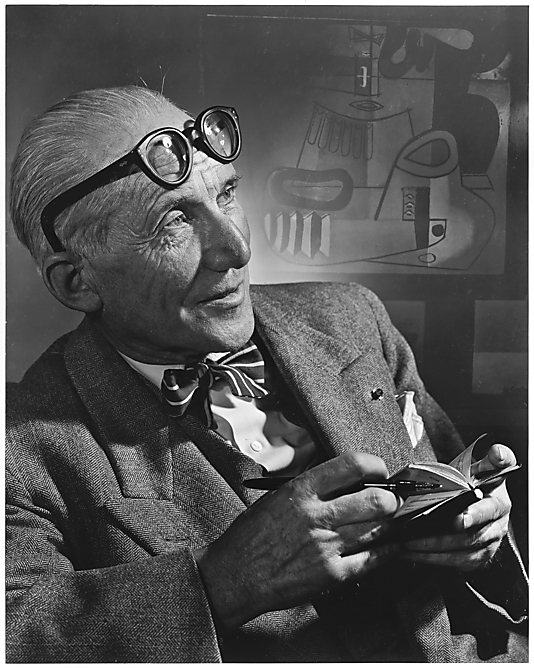

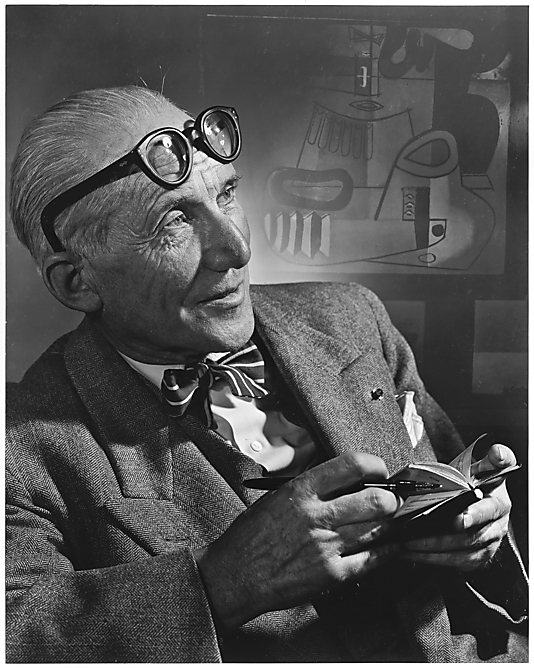

Charles Édouard Jeanneret-Gris (Le Corbusier)

Charles Édouard Jeanneret-Gris (Le Corbusier)

Alfred Hitchcock

Alfred Hitchcock

Christian Dior

Christian Dior

Basquiat smooches his last girlfriend, Kelle Inman, in 1987 in his studio. Inman and Basquiat met when she was working as a waitress at Nell’s; two days later, she was living with him.

Basquiat smooches his last girlfriend, Kelle Inman, in 1987 in his studio. Inman and Basquiat met when she was working as a waitress at Nell’s; two days later, she was living with him.