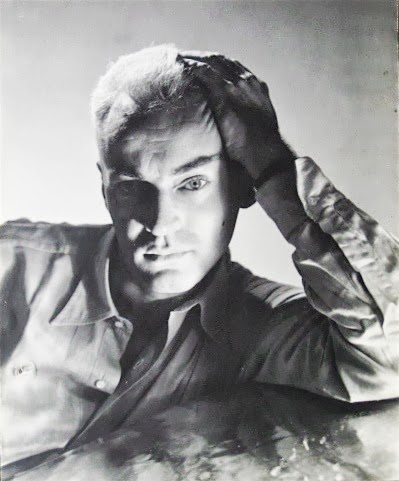

Portrait of Vaslav Nijinsky, by Jacques-Émile Blanche, 1910

Portrait of Vaslav Nijinsky, by Jacques-Émile Blanche, 1910

“…Then, I said to myself:

“HISTORY IS HUMAN NATURE—;

TO SAY I AM GUILTY

IS TO ACCEPT IMPLICATION

IN THE HUMAN RACE. . .”

—Now, for months and months,

I have found

ANOTHER MAN in me—;

HE is NOT me—; I

am afraid of him …”

Frank Bidart

The Sacrifice, released in 1983, received widespread praise. Central to the volume is a thirty-page work titled The War of Vaslav Nijinsky, As with most of his poetry, The War of Vaslav Nijinsky went through a series of revisions as Bidart experimented with language and punctuation. “The Nijinsky poem was a nightmare,” he remarked in his interview. “There is a passage early in it that I got stuck on, and didn’t solve for two years.” David Lehman praised Bidart’s technique of alternating portions of the dancer’s monologue with prose sections on Nijinsky’s life. According to Lehman, “the result combines a documentary effect with an intensity rare in contemporary poetry.”

Bidart’s poem consists almost entirely of a first-person confession by Nijinsky; it takes place after the break with Diaghilev, during the height of war in Europe. We are privy to the dancer’s ideas and musings about, among other things, the second section of The Rite of Spring, called The Sacrifice. Nijinsky’s inner rantings are clearly schizophrenic. He imagines himself the sacrificial victim of the corrupt world that is putting itself through the bloodbath of World War I. The dance is an act of expiation. (The fact that The Rite of Spring was originally the conception of a perfectly sane Stravinsky is glossed over by Bidart.) The Rite of Spring, then, will be an ode to the planet’s renewal after the war, which Nijinsky sees himself as having been chosen by God to enact. But Nijinsky’s (and Stravinsky’s) version will not be the traditional spring ode of birds, trees, and light. It will be the tumultuous, violent, modernist ode to spring, full of blood and death and suffering, for spring involves the death of the old as much as the birth of the new.

Frank Bidart (born on May 27, 1939) is a native of California and considered a career in acting or directing when he was young.In 1957, he began to study at the University of California at Riverside, where he was introduced to writers such as T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound and started to look at poetry as a career path. He then went on to Harvard, where he was a student and friend of Robert Lowell and Elizabeth Bishop. He began studying with Lowell and Reuben Brower in 1962. He has been teaching English at Wellesley College since 1972, and has taught at nearby Brandeis University.

He lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and he is openly gay. currently maintains a strong working relationship with actor and fellow poet James Franco, with whom he collaborated during the making of Franco’s short film Herbert White (2010), based on Bidart’s poem of the same name.