仮面の告白 (Confessions of a Mask) is Japanese author Yukio Mishima‘s second novel. Published in 1949, it launched him to national fame though he was only in his early twenties.

The main protagonist is referred to in the story as Kochan. Being raised during Japan’s era of right-wing militarism and Imperialism, he struggles from a very early age to fit into society. Like Mishima, Kochan was born with a less-than-ideal body in terms of physical fitness and robustness, and throughout the first half of the book (which generally details Kochan’s childhood) struggles intensely to fit into Japanese society. Due to his weakness, Kochan is kept away from boys his own age as he is raised, and is thus not exposed to the norm. This is what likely led to his future fascinations and fantasies of death, violence, and sex. In this way of thinking, some have posited that Mishima is similar.

Kochan is a homosexual, and in the context of Imperial Japan he struggles to keep it to himself. In the early portion of the novel, Kochan does not yet openly admit that he is attracted to men, but indeed professes that he admires masculinity and strength. Some have argued that this, too, is autobiographical of Mishima, himself having worked hard through a naturally weak body to become a superbly fit body builder and male model.

San Sebastiano, Guido Reni, c. 1615

San Sebastiano, Guido Reni, c. 1615

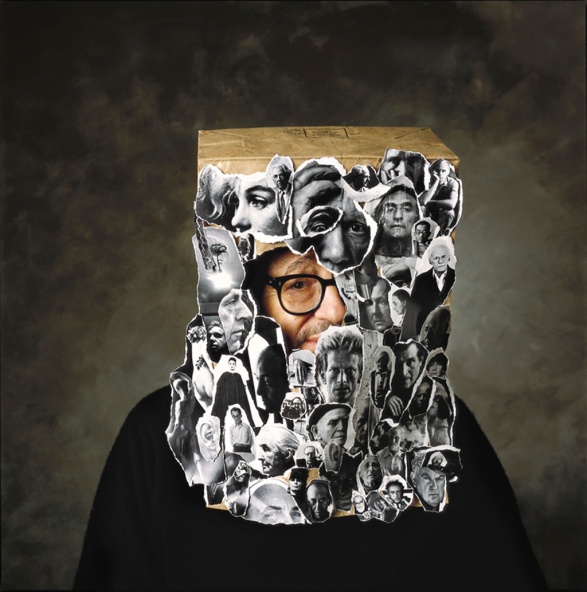

Mishima’s adolescent hero has a very special sexual fantasy after he recognized the high sexual appeal of depictions of St. Sebastian. In fact, his first ejaculation comes from staring at a picture in an art book of a painting of the martyrdom of St. Sebastian. Kochan fantasy is represented on the above cover of Mishima’s novel.Excerpt from Confessions of a Mask, wherein Yukio Mishima recalls his (“his character’s”) first ejaculation and masturbatory experience regarding this image:

Suddenly there came into view from one corner of the next page a picture that I had to believe had been lying in wait there for me, for my sake.

It was a reproduction of Guido Reni’s “St. Sebastian.”

The black and slightly oblique trunk of the tree of execution was seen against a Titian-like background of gloomy forest, and evening sky, somber and distant. A remarkably handsome youth was bound naked to the trunk of the tree. His crossed hands were raised high, and the thongs binding his wrists were tied to the tree. No other bonds were visible, and the only covering for the youth’s nakedness was a coarse white cloth knotted loosely about his loins.

I guess it must be a depiction of a Christian martyrdom. But, as it was painted by an esthetic painter of the eclectic school that derived from the Renaissance, even this painting of death of a christian saint has about it a strong flavor of paganism. The youth’s body—it might even be likened to that of Antinous, beloved of Hadrian, whose beauty has been so often immortalized in sculpture—shows none of the traces of missionary hardship or decrepitude that are to be found in depictions of other saints; instead there is only the springtime of youth, only light and beauty and pleasure.

His white and matchless nudity gleams against a background of dusk. His muscular arms, the arm of a praetorian guard accustomed to bending the bow and wielding of a sword, are raised at a graceful angle and his bound wrists are corssed directly over his head. His face is turned slightly upward and his eyes are open wide, gazing with profound tranquilty upon the glory of heaven. It is not pain that hovers about his straining chest, his tense abdomen, his slightly contorted hips, but some flicker of melancholy pleasure like music. Were it not for the arrows with their shafts deeply sunk into the his left armpit and right side, he would seem more a Roman athlete resting from fatigue, leaning against a dusky tree in a garden.

The arrows have eaten into the tense, fragrant, youthful flesh and are about to consume his body from within with the flames of supreme agony and ecstasy. But there is no flowing blood, nor yet the host of arrows seen in other pictures of Sebastian’s martyrdom. Instead two lone arrows cast their tranquil and graceful shadows upon the smoothness of his skin, like the shadows of a bough falling upon a marble stairway.

But all these interpretations and observations came later.

That day, the instance I looked upon the pictures, my entire being trembled with some pagan joy. My blood soared up; my loins swelled as though in wrath. The monstrous part of me that was on the point of bursting awaited my use of it with unprecedented ardor, upbraiding me for my ignorance, panting indignantly. My hands, completely unconsciously, began a motion they had never been taught. I felt a secret, radiant something rise swift-footed to the attack from inside me. Suddenly it burst forth, bringing with it a blinding intoxication…

Some time passed, and then, with miserable feelings, I looked around the desk I was facing. A maple tree at the window was casting a bright reflection over everything—over the ink bottle, my schoolbooks and notes, the dictionary, the picture of St. Sebastian. There were cloudy-white splashes about—on the gold-imprinted titled of a textbook, on a shoulder of the ink bottle, on one corner of the dictionary. Some objects were dripping lazily, leadenly, and others gleamed dully, like the eyes of a dead fish. Fortunately, a reflex motion of my hand to protect the picture had saved the book from being soiled.

This was my first ejaculation. It was also the beginning, clumsy and completely unpremeditated, of my “bad habit.”

Yukio Mishima’s seppuru. Photo: Tamotsu Yatō

Yukio Mishima’s seppuru. Photo: Tamotsu Yatō