John Lennon received a letter from a pupil at Quarry Bank High School, which he had attended. The writer mentioned that the English master was making his class analyse The Beatles‘ lyrics (Lennon wrote an answer, dated 1 September 1967, which was auctioned by Christie’s of London in 1992). Lennon, amused that a teacher was putting so much effort into understanding the Beatles’ lyrics, decided to write in his next song the most confusing lyrics that he could.

The genesis of the lyrics is found in three song ideas that Lennon was working on, the first of which was inspired by hearing a police siren at his home in Weybridge; Lennon wrote the lines “Mis-ter cit-y police-man” to the rhythm and melody of the siren. The second idea was a short rhyme about Lennon sitting in his garden, while the third was a nonsense lyric about sitting on a corn flake. Unable to finish the ideas as three different songs, he eventually combined them into one. The lyrics also included the phrase “Lucy in the sky” from Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds from Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band earlier in the year.

The Walrus and The Carpenter as illustrated by John Tenniel

The Walrus and The Carpenter as illustrated by John Tenniel

The walrus is a reference to the walrus in Lewis Carroll‘s poem The Walrus and the Carpenter (from the book Through the Looking-Glass). Lennon later expressed dismay upon belatedly realising that the walrus was a villain in the poem.

The final catalyst of the song occurred when Lennon’s friend and former fellow member of the Quarrymen, Peter Shotton, visited and Lennon asked Shotton about a playground nursery rhyme they sang as children. Shotton remembered:

“Yellow matter custard, green slop pie, All mixed together with a dead dog’s eye, Slap it on a butty, ten foot thick, Then wash it all down with a cup of cold sick.”

Lennon borrowed a couple of words, added the three unfinished ideas and the result was I Am the Walrus. The Beatles’ official biographer Hunter Davies was present while the song was being written and wrote an account in his 1968 biography of the Beatles. Lennon remarked to Shotton, “Let the fuckers work that one out.” Shotton was also responsible for suggesting to Lennon to change the lyric “waiting for the man to come” to “waiting for the van to come”.

The Beatles in costume filming Magical Mystery Tour

The Beatles in costume filming Magical Mystery Tour

Lennon claimed he wrote the first two lines on separate acid trips; he explained much of the song to Playboy in 1980:

“The first line was written on one acid trip one weekend. The second line was written on the next acid trip the next weekend, and it was filled in after I met Yoko… I’d seen Allen Ginsberg and some other people who liked Dylan and Jesus going on about Hare Krishna. It was Ginsberg, in particular, I was referring to. The words ‘Element’ry penguin’ meant that it’s naïve to just go around chanting Hare Krishna or putting all your faith in one idol. In those days I was writing obscurely, à la Dylan.”

“It never dawned on me that Lewis Carroll was commenting on the capitalist system. I never went into that bit about what he really meant, like people are doing with the Beatles’ work. Later, I went back and looked at it and realized that the walrus was the bad guy in the story and the carpenter was the good guy. I thought, Oh, shit, I picked the wrong guy. I should have said, ‘I am the carpenter.’ But that wouldn’t have been the same, would it? [Sings, laughing] ‘I am the carpenter….'”

Seen in the Magical Mystery Tour film singing the song, Lennon, apparently, is the walrus; on the track-list of the accompanying soundtrack EP/LP however, underneath I Am the Walrus are printed the words ‘ “No you’re not!” said Little Nicola’ (in the film, Nicola is a little girl who keeps contradicting everything the other characters say). Lennon returned to the subject in the lyrics of three of his subsequent songs: in the 1968 Beatles song Glass Onion he sings, “I told you ’bout the walrus and me, man/You know that we’re as close as can be, man/Well here’s another clue for you all/The walrus was Paul”; in the third verse of Come Together he sings the line “he bag production, he got walrus gumboot”; and in his 1970 solo song God, admits “I was the walrus, but now I’m John.”

To watch the clip from Magical Mystery Tour, please take a gander at The Genealogy of the Style‘s Facebook page: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7r52ZBx0KMI

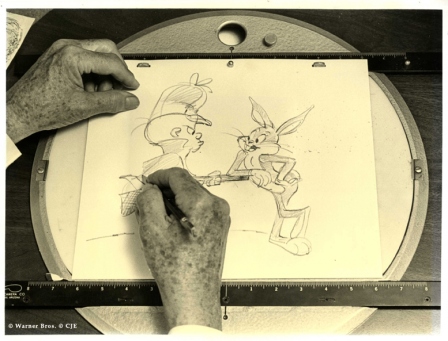

Chuck Jones and Bugs Bunny

Chuck Jones and Bugs Bunny