By Patty Smith

from Details, November 1992

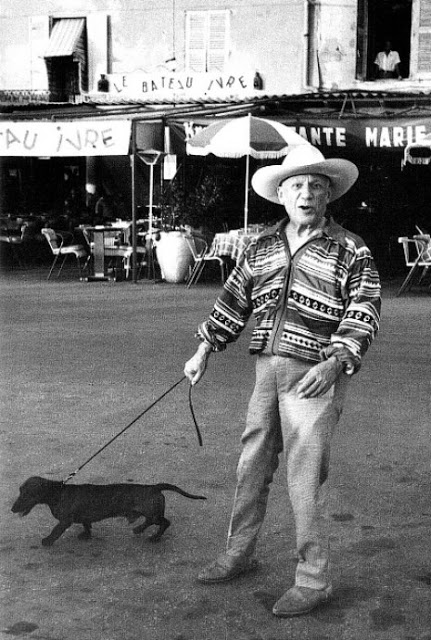

Self-Portrait, Robert Mapplethorpe, 1985

Self-Portrait, Robert Mapplethorpe, 1985

“When Robert and I were young, scarcely twenty, we’d sometimes go to Coney Island, have a Nathan’s hot dog, sit on the long pier, and dream about the future. Robert wanted to be a rich and famous artist. (He did it.) I wanted to do something great. (I’m still working on it.) We’d cast our wishes like the shoeless kids and old men who cast out their fishing lines. We’d sit there until dawn, then head back into Brooklyn. We were never afraid. New York was tough but kind. We were always all right. Maybe just a little hungry.

It was the summer of 1967. I had left the security of family, cornfields, and billowing New Jersey skies to seek my fortune in New York. I met Robert, a smiling, barefoot kid as misfit as myself. That fall, we got a place on Hall Street in Brooklyn, across from Pratt Institute, where he was a student. The streets were run by painters and poets. Everybody had a vision. Everybody was broke. Nobody had a TV.

Ours was a bleak little apartment that he brightened with Indian cloths, religious objects, and his own work. I tacked pictures of Rimbaud over my writing desk, played my Juliet Gréco records, and read Illuminations. Robert had a Timothy Leary book–one of the few books he actually read. (He often fell asleep in foreign movies. It was the subtitles, he said.) He was always working on a drawing, an installation, or a new piece of sculpture. He’d work twelve hours straight, listening to the same Vanilla Fudge album over and over. His work was asymmetric, psychedelic, and he was always scavenging for materials. I had to hide my best stuff, for many a wolf skin, brocade, or crucifix was sacrificed on the altar of art.

At twenty, we were still learning about ourselves, trying to make sense of what was going down. Assassinations, Vietnam, universal love, where our next meal was coming from. New York was going though its own changes–the Beat residue of the early ’60s was giving way to the divine disorder of 1968. All this was new to me–beaded curtains and LSD were not big sellers in South Jersey.

Robert and I rarely fought. We did bicker, though, like siblings, over everything. Trivial things. Who would do the laundry. Who would get the last sheet of drawing paper. Who was the better dancer. (He refused to acknowledge the superiority of my South Jersey over his own Long Island style.) What to eat. All he ever wanted was spaghetti and chocolate egg creams.

Our main preoccupations were art and magic. Magic was an intuitive thing you either had or you didn’t, and Robert was sure he had it. It was a gift from God, and he pinned his faith upon it. I always admired his confidence. It wasn’t arrogance, it was just there, unshakable. And he was generous with it–if he believed in what you were doing, he somehow infected you with it. His major source of anxiety was money, because executing his ideas required it and he loathed employment.

We were not the hippest people. That was not the thing. The thing was to develop a vision that would be worthy of remembrance, or even a bit of glory.

Sometimes we’d pass the night by sitting on the floor, looking at books. Some my mother gave me: The Fabulous Life of Diego Rivera, Brancusi, The Sacred Art of Tibet. And his own big coffee-table books on erotic art, Tantric art, and Surrealism. I’d plait my hair like Frida Kahlo, he’d stretch out in an old black turtleneck and dungarees, and we’d find refuge in the pages and emerge inspired, full of resolve.

Robert loved the large-format book. He wasn’t much of a reader, but he’d study the plates–the work of Michelangelo, Blake, Duchamp–and extend what he saw in works of his own. He dreamed of having such a book someday, devoted to his own particular vision that was, in the late ’60s, still forming.

This was on my mind recently when I opened the package containing the unbound sheets of his forthcoming book, Mapplethorpe. A large, exquisite book, admittedly not for every coffee table, but coffee-table size, just as he wanted. It forms a visual diary of his life, opening not with his name, nor a text, but with an image of a proud, frayed American flag. The stars block, and are therefore illuminated by, the sun. Toward the end of the book is one of his last self-portraits, in which he is aged considerably from physical suffering, stubborn, stoic, and a bit frayed, like the proud and weathered flag.

Robert took his first pictures in 1970. We had parted as a couple, but we stayed together as friends. We tackled Manhattan: The Chelsea Hotel. Max’s Kansas City. The Factory. The ’70s. Robert loved Manhattan, its perpetual twilight. He felt alive there, free. He loved socializing-even though he was shy–and he loved Andy Warhol, who was also shy and loved to socialize.

Like many exploring their sexual identity at that time, he cased the emerging frontier. Christopher Street. Forty-second Street. The leather, bars. The baths. He shifted identities, not out of crisis, but out of delight. One month, the sailor; the next, the hustler. “How do you like this new image!” he’d ask, pleased with himself in a black net T-shirt, tight pants, and a piece of red silk tied around his throat. In that same black net tee he hung out on Fifty- third Street, where he observed the hustlers, photographed the hustlers, and perhaps hustled himself. He wore the T-shirt executing art. And when he finally took it off, he stretched and mounted it on a frame and exposed it as art itself.

He was using at this time an old Polaroid. A pack of film was costly and might take the place of a meal, so each shot was important. Robert never took snapshots. He always knew beforehand the image he was after. He followed me around with that Polaroid constantly, issuing simple commands. “Can you stand in that shaft of light?” “Slowly face the wall.” Each shot taken with a studied economy, an economy he employed throughout his working life. Even later, as his work developed, he never used a motor drive, never shot roll after roll. His process was not a passionate one. His work was the result of a contemplative, deliberate act. He never drew lines; he crossed them, without apology, to create something present, new. A contact sheet would reveal just twelve images. They were all alike, except for the one he had marked, the perfect one. “The one with the magic,” he’d say.

I admit I hoped his photography was a passing phase. Somehow, being shot with a cheap Polaroid didn’t correspond to my notion of the role of the French artist’s model. But he took it seriously. He liked the speed, the immediacy. He was convinced that the common Polaroid print, in his hands, was a viable work of art.

He drew his subjects from life’s walk, and his work reflected change–both personal and social. Many of his models were biker boys, call boys, men of the street. His form was classic, stylized–“I’m not after beauty,” he would say, “I’m after perfection, and they’re not always the same.”

In the early ’70s he began to use the large-format camera, and he committed himself to photography, championing its elevation and exploration. Portraits, still lifes, early flowers, the S&M suite. At first I found the S&M photographs, which were difficult by most standards, frightening. I once asked him what it was like being there, observing, immortalizing the private rituals of these people. He said it was “somewhat scary. But they know what they’re doing. And so do I. It’s all about trust.” He used these photographs, which caused such a stir years later, to tease me relentlessly. He knew I was squeamish about them, and he’d slip prints into my books. So on a rainy Sunday, I’d open a beautiful copy of Peter Pan or Arabia Deserta and be assaulted by an image of a bloodied member in a vice grip. “Robert!” I’d yell. And I could hear him, through the wall that separated our studios, giggling.

I think the furor his work caused after his death would have amused him. But the attention paid to just the sexual aspect would have surely dismayed him. He was not intentionally political. He was not an activist. He shot what he saw–just as Genet wrote what he experienced–with grace. All his work–from the translucent skin of a lily to the arched torso of a black male–represented him, his vision of the world. Just as Pollock hated being called an Abstract Expressionist and Manet deplored the title Impressionist, Robert never wanted to be pegged. Not even as a photographer. The true artist desires, and deserves, to be remembered only as an Artist.

Shortly before he died, I sat with Robert in his studio. He still worked, despite terrible bouts of coughing, vomiting, and excruciating pain. With the aid of his youngest brother, the photographer Edward Maxey, he was able to produce some final, perfect images. We sat amongst large, exquisite prints. A cluster of deeply ripe grapes. A single rose. And a marble portrait of Hermes. The skin of the white statue burned and seemed to emit its own light against a field of black. It was as if, through Robert’s eye, it had glimpsed life.

“I think I’ve done everything I can with the photograph,” he said. “I think I’ll go back to sculpture.”

He had on that day the anxious, fervent gaze he often wore when he worked. I remember that same look as he photographed me in Burbank, California, in full sun before a drying palm. It was 1987, I was six months pregnant and feeling the strain. Robert was not well. His hand trembled and, as he worked, he dropped and broke his light meter. But we took the picture anyway, barely saying a word. He checked the image and drew the camera closer. “Can you raise your head just a little!” It was much like the first pictures. High concentration. Simple and direct. Within that modest photograph is all our experience, compassion,, and even a mutual sense of irony. He was carrying death. I was carrying life. My hair is braided and the sun is in my eyes. And so is an image of Robert, alive.”