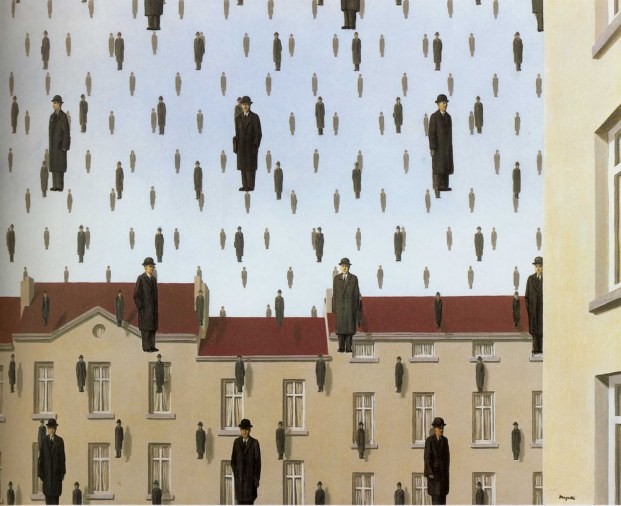

Les Vacances de Hegel (Hegel’s Holiday), René Magritte, 1958

ICH BETE WIEDER, DU ERLAUCHTER

Ich bete wieder, du Erlauchter,

du hörst mich wieder durch den Wind,

weil meine Tiefen nie gebrauchter

rauschender Worte mächtig sind.

Ich war zerstreut; an Widersacher

in Stücken war verteilt mein Ich.

O Gott, mich lachten alle Lacher,

und alle Trinker tranken mich

__________________________

I pray again, you Illustrious One;

do you hear me again through the wind

because from my unused depths

mighty words are rushing.

I was dispersed; to the adversary

my self was given in pieces.

O God, I laughed all laughter,

and all drunkards drank me.

Le clef des champs (The Key to the Fields) , 1936

Le clef des champs (The Key to the Fields) , 1936

Ich war ein Haus nach einem Brand,

darin nur Mörder manchmal schlafen,

eh ihre hungerigen Strafen

sie weiterjagen in das Land;

ich war wie eine Stadt am Meer,

wenn eine Seuche sie bedrängte,

die sich wie eine Leiche schwer

den Kindern in die Hände hängte.

__________________________

I was a house after a fire,

where only murderers sometimes sleep,

and their hungry punishments

pursue them through the land;

I was like a city on the sea,

pressed by a plague,

which like a heavy corpse

hung the children in the hands.

Not to be Reproduced (La reproduction interdite), a portrait of Edward James by René Magritte, 1937

Not to be Reproduced (La reproduction interdite), a portrait of Edward James by René Magritte, 1937

Ich war mir fremd wie irgendwer

und wußte nur von ihm, daß er

einst meine junge Mutter kränkte,

als sie mich trug,

und daß ihr Herz, das eingeengte,

sehr schmerzhaft an mein Keimen schlug.

__________________________

I was a stranger to myself as one

of whom I knew only that he

once offended my young mother

as she carried me

and that her heart, thus constricted,

throbbed achingly about my sprouting self.

Jetzt bin ich wieder aufgebaut

aus allen Stücken meiner Schande

und sehne mich nach einem Bande,

nach einem einigen Verstande,

der mich wie ein Ding überschaut, –

nach deines Herzens großen Händen –

(o kämen sie doch auf mich zu)ich zähle mich, mein Gott, und du,

du hast das Recht, mich zu verschwenden.

__________________________

Now I am rebuilt

from all the pieces of my shame

and yearn for a bond,

for a unified understanding,

which regards me as one thing

– as I yearn for the big hands of your Heart [to

me]

(oh, let them draw near me)

I count myself, my God, and you,

You have the right, to waste me.

Rainer Maria Rilke

From The Book of Hours

Translation by Anita Barrows and Joanna Macy