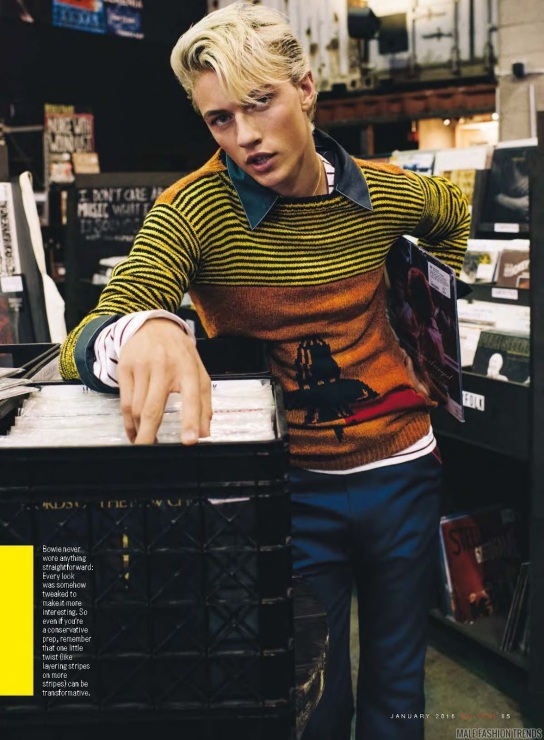

Model: Lucky Blue Smith

Photographer: Sebastian Kim

GQ, January 2016

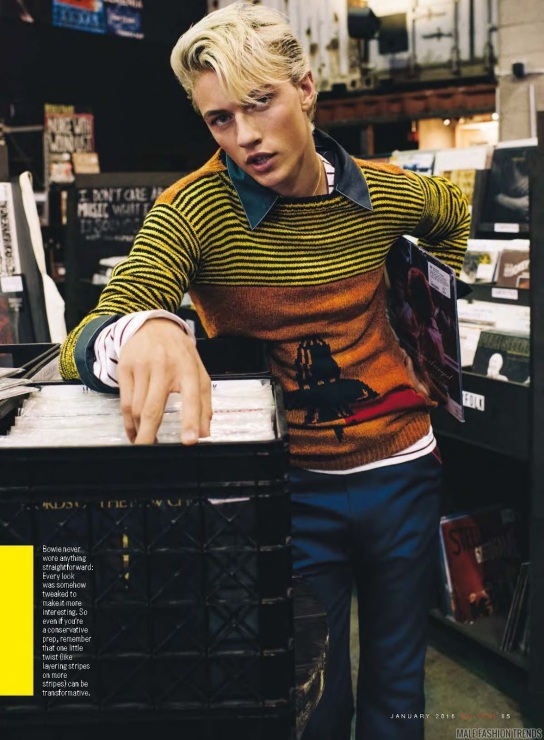

Model: Lucky Blue Smith

Photographer: Sebastian Kim

GQ, January 2016

«…Dürer portrayed himself as the Christus. Robert often fantasized and photographed himself as the Christus.»

Jack Fritscher

Mapplethorpe: Assault with a Deadly Camera

Portrait of Patti Smith by Robert Mapplethorpe, 1986

Portrait of Patti Smith by Robert Mapplethorpe, 1986

Self-Portrait at Twenty-Eight Years Old Wearing a Coat with Fur Collar, Albrecht Dürer, 1500

Self-Portrait at Twenty-Eight Years Old Wearing a Coat with Fur Collar, Albrecht Dürer, 1500

Painted early in 1500, just before his 29th birthday, it is the last of his three painted self-portraits. It is considered the most personal, iconic and complex of his self-portraits, and the one that has become fixed in the popular imagination. The self-portrait is most remarkable because of its resemblance to many earlier representations of Christ. Art historians note the similarities with the conventions of religious painting, including its symmetry, dark tones and the manner in which the artist directly confronts the viewer and raises his hands to the middle of his chest as if in the act of blessing.

Blessing Christ, Hans Memling, circa 1433–1494

Blessing Christ, Hans Memling, circa 1433–1494

Dürer chooses to present himself monumentally, in a style that unmistakably recalls depictions of Christ—the implications of which have been debated among art critics. A conservative interpretation suggests that he is responding to the tradition of the Imitation of Christ. A more controversial view reads the painting is a proclamation of the artist’s supreme role as creator. This latter view is supported by the painting’s Latin inscription, composed by Celtes’ personal secretary, which translates as; “I, Albrecht Dürer of Nuremberg portrayed myself in appropriate [or everlasting] colours aged twenty-eight years”.

Signatura rerum (The Theory of signature), orchids images from G.B. Della Porta (1588)

Signatura rerum (The Theory of signature), orchids images from G.B. Della Porta (1588)

The Ara Pacis, an altar erected in Rome by the emperor Augustus in 9 B.C.E., includes one of the earliest documented depictions of an orchid (inset) in Western art. Credit: Bernd Haynold

The Ara Pacis, an altar erected in Rome by the emperor Augustus in 9 B.C.E., includes one of the earliest documented depictions of an orchid (inset) in Western art. Credit: Bernd Haynold

Orchidaceae is a diverse and widespread family of flowering plants, with blooms that are often colourful and often fragrant. The type genus (i.e. the genus after which the family is named) is Orchis. The genus name comes from the Ancient Greek ὄρχις (órkhis), literally meaning “testicle”, because of the shape of the twin tubers in some species of Orchis. The term “orchid” was introduced in 1845 by John Lindley in School Botany, as a shortened form of Orchidaceae. All orchids are perennial herbs that lack any permanent woody structure.

The depictions of Italian orchids showed up much earlier than expected. Previously they were spotted in paintings in the 1400s, but Caneva’s team discovered them as early as 46 B.C.E, when Julius Caesar erected the Temple of Venus Genetrix in Rome. There are at least three orchids appearing in dozens of other plants on the Ara Pacis. Artists chose the flowers to emphasize a theme of civic rebirth, fertility and prosperity following a long period of conflict.

As Christianity began to influence art in the 3rd and 4th centuries, orchids and other plants began to fade from public art. This was probably due to an effort to eliminate pagan symbols and those related to sexuality. With the arrival of the Renaissance, orchids arrive back in art, but now mostly as a symbol of beauty and elegance.

Photograph by Robert Mapplethorpe, circa 1986

Photograph by Robert Mapplethorpe, circa 1986

“Nodding though, the lamp’s lit low, nod for passers

underground

To and fro, she’s darning and the land is weeping red

and pale

Weeping yarn from Algiers,

weeping yarn from Algiers

Weaving though, the eyes are pale, what will rend,

will also mend

The sifting cloth is binding and the dream she weaves

will never end

For we’re marching toward Algiers,

for we’re marching toward Algiers

Lullaby though, baby’s gone,

lullaby a broken song

Oh, the cradle was our call,

when it rocked we carried on

And we marched on toward Algiers,

for we’re marching for Algiers

We’re still marching for Algiers,

marching, marching for Algiers

Not to hail a barren sky,

sifting cloth is weeping red

The mourning veil is waving high a field of stars

and tears we’ve shed

In the sky a broken flag, children wave and raise their arms

We’ll be gone but they’ll go on and on and on and on and on”

Patti Smith

Waves

1979

Photographs by Robert Mapplethorpe

Photographs by Robert Mapplethorpe

By Patty Smith

from Details, November 1992

Self-Portrait, Robert Mapplethorpe, 1985

Self-Portrait, Robert Mapplethorpe, 1985

“When Robert and I were young, scarcely twenty, we’d sometimes go to Coney Island, have a Nathan’s hot dog, sit on the long pier, and dream about the future. Robert wanted to be a rich and famous artist. (He did it.) I wanted to do something great. (I’m still working on it.) We’d cast our wishes like the shoeless kids and old men who cast out their fishing lines. We’d sit there until dawn, then head back into Brooklyn. We were never afraid. New York was tough but kind. We were always all right. Maybe just a little hungry.

It was the summer of 1967. I had left the security of family, cornfields, and billowing New Jersey skies to seek my fortune in New York. I met Robert, a smiling, barefoot kid as misfit as myself. That fall, we got a place on Hall Street in Brooklyn, across from Pratt Institute, where he was a student. The streets were run by painters and poets. Everybody had a vision. Everybody was broke. Nobody had a TV.

Ours was a bleak little apartment that he brightened with Indian cloths, religious objects, and his own work. I tacked pictures of Rimbaud over my writing desk, played my Juliet Gréco records, and read Illuminations. Robert had a Timothy Leary book–one of the few books he actually read. (He often fell asleep in foreign movies. It was the subtitles, he said.) He was always working on a drawing, an installation, or a new piece of sculpture. He’d work twelve hours straight, listening to the same Vanilla Fudge album over and over. His work was asymmetric, psychedelic, and he was always scavenging for materials. I had to hide my best stuff, for many a wolf skin, brocade, or crucifix was sacrificed on the altar of art.

At twenty, we were still learning about ourselves, trying to make sense of what was going down. Assassinations, Vietnam, universal love, where our next meal was coming from. New York was going though its own changes–the Beat residue of the early ’60s was giving way to the divine disorder of 1968. All this was new to me–beaded curtains and LSD were not big sellers in South Jersey.

Robert and I rarely fought. We did bicker, though, like siblings, over everything. Trivial things. Who would do the laundry. Who would get the last sheet of drawing paper. Who was the better dancer. (He refused to acknowledge the superiority of my South Jersey over his own Long Island style.) What to eat. All he ever wanted was spaghetti and chocolate egg creams.

Our main preoccupations were art and magic. Magic was an intuitive thing you either had or you didn’t, and Robert was sure he had it. It was a gift from God, and he pinned his faith upon it. I always admired his confidence. It wasn’t arrogance, it was just there, unshakable. And he was generous with it–if he believed in what you were doing, he somehow infected you with it. His major source of anxiety was money, because executing his ideas required it and he loathed employment.

We were not the hippest people. That was not the thing. The thing was to develop a vision that would be worthy of remembrance, or even a bit of glory.

Sometimes we’d pass the night by sitting on the floor, looking at books. Some my mother gave me: The Fabulous Life of Diego Rivera, Brancusi, The Sacred Art of Tibet. And his own big coffee-table books on erotic art, Tantric art, and Surrealism. I’d plait my hair like Frida Kahlo, he’d stretch out in an old black turtleneck and dungarees, and we’d find refuge in the pages and emerge inspired, full of resolve.

Robert loved the large-format book. He wasn’t much of a reader, but he’d study the plates–the work of Michelangelo, Blake, Duchamp–and extend what he saw in works of his own. He dreamed of having such a book someday, devoted to his own particular vision that was, in the late ’60s, still forming.

This was on my mind recently when I opened the package containing the unbound sheets of his forthcoming book, Mapplethorpe. A large, exquisite book, admittedly not for every coffee table, but coffee-table size, just as he wanted. It forms a visual diary of his life, opening not with his name, nor a text, but with an image of a proud, frayed American flag. The stars block, and are therefore illuminated by, the sun. Toward the end of the book is one of his last self-portraits, in which he is aged considerably from physical suffering, stubborn, stoic, and a bit frayed, like the proud and weathered flag.

Robert took his first pictures in 1970. We had parted as a couple, but we stayed together as friends. We tackled Manhattan: The Chelsea Hotel. Max’s Kansas City. The Factory. The ’70s. Robert loved Manhattan, its perpetual twilight. He felt alive there, free. He loved socializing-even though he was shy–and he loved Andy Warhol, who was also shy and loved to socialize.

Like many exploring their sexual identity at that time, he cased the emerging frontier. Christopher Street. Forty-second Street. The leather, bars. The baths. He shifted identities, not out of crisis, but out of delight. One month, the sailor; the next, the hustler. “How do you like this new image!” he’d ask, pleased with himself in a black net T-shirt, tight pants, and a piece of red silk tied around his throat. In that same black net tee he hung out on Fifty- third Street, where he observed the hustlers, photographed the hustlers, and perhaps hustled himself. He wore the T-shirt executing art. And when he finally took it off, he stretched and mounted it on a frame and exposed it as art itself.

He was using at this time an old Polaroid. A pack of film was costly and might take the place of a meal, so each shot was important. Robert never took snapshots. He always knew beforehand the image he was after. He followed me around with that Polaroid constantly, issuing simple commands. “Can you stand in that shaft of light?” “Slowly face the wall.” Each shot taken with a studied economy, an economy he employed throughout his working life. Even later, as his work developed, he never used a motor drive, never shot roll after roll. His process was not a passionate one. His work was the result of a contemplative, deliberate act. He never drew lines; he crossed them, without apology, to create something present, new. A contact sheet would reveal just twelve images. They were all alike, except for the one he had marked, the perfect one. “The one with the magic,” he’d say.

I admit I hoped his photography was a passing phase. Somehow, being shot with a cheap Polaroid didn’t correspond to my notion of the role of the French artist’s model. But he took it seriously. He liked the speed, the immediacy. He was convinced that the common Polaroid print, in his hands, was a viable work of art.

He drew his subjects from life’s walk, and his work reflected change–both personal and social. Many of his models were biker boys, call boys, men of the street. His form was classic, stylized–“I’m not after beauty,” he would say, “I’m after perfection, and they’re not always the same.”

In the early ’70s he began to use the large-format camera, and he committed himself to photography, championing its elevation and exploration. Portraits, still lifes, early flowers, the S&M suite. At first I found the S&M photographs, which were difficult by most standards, frightening. I once asked him what it was like being there, observing, immortalizing the private rituals of these people. He said it was “somewhat scary. But they know what they’re doing. And so do I. It’s all about trust.” He used these photographs, which caused such a stir years later, to tease me relentlessly. He knew I was squeamish about them, and he’d slip prints into my books. So on a rainy Sunday, I’d open a beautiful copy of Peter Pan or Arabia Deserta and be assaulted by an image of a bloodied member in a vice grip. “Robert!” I’d yell. And I could hear him, through the wall that separated our studios, giggling.

I think the furor his work caused after his death would have amused him. But the attention paid to just the sexual aspect would have surely dismayed him. He was not intentionally political. He was not an activist. He shot what he saw–just as Genet wrote what he experienced–with grace. All his work–from the translucent skin of a lily to the arched torso of a black male–represented him, his vision of the world. Just as Pollock hated being called an Abstract Expressionist and Manet deplored the title Impressionist, Robert never wanted to be pegged. Not even as a photographer. The true artist desires, and deserves, to be remembered only as an Artist.

Shortly before he died, I sat with Robert in his studio. He still worked, despite terrible bouts of coughing, vomiting, and excruciating pain. With the aid of his youngest brother, the photographer Edward Maxey, he was able to produce some final, perfect images. We sat amongst large, exquisite prints. A cluster of deeply ripe grapes. A single rose. And a marble portrait of Hermes. The skin of the white statue burned and seemed to emit its own light against a field of black. It was as if, through Robert’s eye, it had glimpsed life.

“I think I’ve done everything I can with the photograph,” he said. “I think I’ll go back to sculpture.”

He had on that day the anxious, fervent gaze he often wore when he worked. I remember that same look as he photographed me in Burbank, California, in full sun before a drying palm. It was 1987, I was six months pregnant and feeling the strain. Robert was not well. His hand trembled and, as he worked, he dropped and broke his light meter. But we took the picture anyway, barely saying a word. He checked the image and drew the camera closer. “Can you raise your head just a little!” It was much like the first pictures. High concentration. Simple and direct. Within that modest photograph is all our experience, compassion,, and even a mutual sense of irony. He was carrying death. I was carrying life. My hair is braided and the sun is in my eyes. And so is an image of Robert, alive.”

Patti Smith (Boat to Fire Island), Robert Mapplethorpe, circa 1971-74

Patti Smith (Boat to Fire Island), Robert Mapplethorpe, circa 1971-74

LE BATEAU IVRE

Comme je descendais des Fleuves impassibles,

Je ne me sentis plus guidé par les haleurs :

Des Peaux-Rouges criards les avaient pris pour cibles,

Les ayant cloués nus aux poteaux de couleurs.

J’étais insoucieux de tous les équipages,

Porteur de blés flamands ou de cotons anglais.

Quand avec mes haleurs ont fini ces tapages,

Les Fleuves m’ont laissé descendre où je voulais.

Dans les clapotements furieux des marées,

Moi, l’autre hiver, plus sourd que les cerveaux d’enfants,

Je courus ! Et les Péninsules démarrées

N’ont pas subi tohu-bohus plus triomphants.

La tempête a béni mes éveils maritimes.

Plus léger qu’un bouchon j’ai dansé sur les flots

Qu’on appelle rouleurs éternels de victimes,

Dix nuits, sans regretter l’oeil niais des falots!

Plus douce qu’aux enfants la chair des pommes sûres,

L’eau verte pénétra ma coque de sapin

Et des taches de vins bleus et des vomissures

Me lava, dispersant gouvernail et grappin.

Et dès lors, je me suis baigné dans le Poème

De la Mer, infusé d’astres, et lactescent,

Dévorant les azurs verts ; où, flottaison blême

Et ravie, un noyé pensif parfois descend;

Où, teignant tout à coup les bleuités, délires

Et rhythmes lents sous les rutilements du jour,

Plus fortes que l’alcool, plus vastes que nos lyres,

Fermentent les rousseurs amères de l’amour!

Je sais les cieux crevant en éclairs, et les trombes

Et les ressacs et les courants : je sais le soir,

L’Aube exaltée ainsi qu’un peuple de colombes,

Et j’ai vu quelquefois ce que l’homme a cru voir!

J’ai vu le soleil bas, taché d’horreurs mystiques,

Illuminant de longs figements violets,

Pareils à des acteurs de drames très antiques

Les flots roulant au loin leurs frissons de volets!

J’ai rêvé la nuit verte aux neiges éblouies,

Baiser montant aux yeux des mers avec lenteurs,

La circulation des sèves inouïes,

Et l’éveil jaune et bleu des phosphores chanteurs!

J’ai suivi, des mois pleins, pareille aux vacheries

Hystériques, la houle à l’assaut des récifs,

Sans songer que les pieds lumineux des Maries

Pussent forcer le mufle aux Océans poussifs!

J’ai heurté, savez-vous, d’incroyables Florides

Mêlant aux fleurs des yeux de panthères à peaux

D’hommes ! Des arcs-en-ciel tendus comme des brides

Sous l’horizon des mers, à de glauques troupeaux!

J’ai vu fermenter les marais énormes, nasses

Où pourrit dans les joncs tout un Léviathan!

Des écroulements d’eaux au milieu des bonaces,

Et les lointains vers les gouffres cataractant!

Glaciers, soleils d’argent, flots nacreux, cieux de braises!

Échouages hideux au fond des golfes bruns

Où les serpents géants dévorés des punaises

Choient, des arbres tordus, avec de noirs parfums!

J’aurais voulu montrer aux enfants ces dorades

Du flot bleu, ces poissons d’or, ces poissons chantants.

– Des écumes de fleurs ont bercé mes dérades

Et d’ineffables vents m’ont ailé par instants.

Parfois, martyr lassé des pôles et des zones,

La mer dont le sanglot faisait mon roulis doux

Montait vers moi ses fleurs d’ombre aux ventouses jaunes

Et je restais, ainsi qu’une femme à genoux…

Presque île, ballottant sur mes bords les querelles

Et les fientes d’oiseaux clabaudeurs aux yeux blonds.

Et je voguais, lorsqu’à travers mes liens frêles

Des noyés descendaient dormir, à reculons!

Or moi, bateau perdu sous les cheveux des anses,

Jeté par l’ouragan dans l’éther sans oiseau,

Moi dont les Monitors et les voiliers des Hanses

N’auraient pas repêché la carcasse ivre d’eau;

Libre, fumant, monté de brumes violettes,

Moi qui trouais le ciel rougeoyant comme un mur

Qui porte, confiture exquise aux bons poètes,

Des lichens de soleil et des morves d’azur;

Qui courais, taché de lunules électriques,

Planche folle, escorté des hippocampes noirs,

Quand les juillets faisaient crouler à coups de triques

Les cieux ultramarins aux ardents entonnoirs;

Moi qui tremblais, sentant geindre à cinquante lieues

Le rut des Béhémots et les Maelstroms épais,

Fileur éternel des immobilités bleues,

Je regrette l’Europe aux anciens parapets!

J’ai vu des archipels sidéraux ! et des îles

Dont les cieux délirants sont ouverts au vogueur :

– Est-ce en ces nuits sans fonds que tu dors et t’exiles,

Million d’oiseaux d’or, ô future Vigueur?

Mais, vrai, j’ai trop pleuré ! Les Aubes sont navrantes.

Toute lune est atroce et tout soleil amer :

L’âcre amour m’a gonflé de torpeurs enivrantes.

Ô que ma quille éclate ! Ô que j’aille à la mer!

Si je désire une eau d’Europe, c’est la flache

Noire et froide où vers le crépuscule embaumé

Un enfant accroupi plein de tristesse, lâche

Un bateau frêle comme un papillon de mai.

Je ne puis plus, baigné de vos langueurs, ô lames,

Enlever leur sillage aux porteurs de cotons,

Ni traverser l’orgueil des drapeaux et des flammes,

Ni nager sous les yeux horribles des pontons.

Arthur Rimbaud

1871

__________________________________

“As I was going down impassive Rivers,

I no longer felt myself guided by haulers:

Yelping redskins had taken them as targets

And had nailed them naked to colored stakes.

I was indifferent to all crews,

The bearer of Flemish wheat or English cottons

When with my haulers this uproar stopped

The Rivers let me go where I wanted.

Into the furious lashing of the tides

More heedless than children’s brains the other winter

I ran! And loosened Peninsulas

Have not undergone a more triumphant hubbub

The storm blessed my sea vigils

Lighter than a cork I danced on the waves

That are called eternal rollers of victims,

Ten nights, without missing the stupid eye of the lighthouses!

Sweeter than the flesh of hard apples is to children

The green water penetrated my hull of fir

And washed me of spots of blue wine

And vomit, scattering rudder and grappling-hook

And from then on I bathed in the Poem

Of the Sea, infused with stars and lactescent,

Devouring the azure verses; where, like a pale elated

Piece of flotsam, a pensive drowned figure sometimes sinks;

Where, suddenly dyeing the blueness, delirium

And slow rhythms under the streaking of daylight,

Stronger than alcohol, vaster than our lyres,

The bitter redness of love ferments!

I know the skies bursting with lightning, and the waterspouts

And the surf and the currents; I know the evening,

And dawn as exalted as a flock of doves

And at times I have seen what man thought he saw!

I have seen the low sun spotted with mystic horrors,

Lighting up, with long violet clots,

Resembling actors of very ancient dramas,

The waves rolling far off their quivering of shutters!

I have dreamed of the green night with dazzled snows

A kiss slowly rising to the eyes of the sea,

The circulation of unknown saps,

And the yellow and blue awakening of singing phosphorous!

I followed during pregnant months the swell,

Like hysterical cows, in its assault on the reefs,

Without dreaming that the luminous feet of the Marys

Could constrain the snout of the wheezing Oceans!

I struck against, you know, unbelievable Floridas

Mingling with flowers panthers’ eyes and human

Skin! Rainbows stretched like bridal reins

Under the horizon of the seas to greenish herds!

I have seen enormous swamps ferment, fish-traps

Where a whole Leviathan rots in the rushes!

Avalanches of water in the midst of a calm,

And the distances cataracting toward the abyss!

Glaciers, suns of silver, nacreous waves, skies of embers!

Hideous strands at the end of brown gulfs

Where giant serpents devoured by bedbugs

Fall down from gnarled trees with black scent!

I should have liked to show children those sunfish

Of the blue wave, the fish of gold, the singing fish.

—Foam of flowers rocked my drifting

And ineffable winds winged me at times.

At times a martyr weary of poles and zones,

The sea, whose sob created my gentle roll,

Brought up to me her dark flowers with yellow suckers

And I remained, like a woman on her knees…

Resembling an island tossing on my sides the quarrels

And droppings of noisy birds with yellow eyes

And I sailed on, when through my fragile ropes

Drowned men sank backward to sleep!

Now I, a boat lost in the foliage of caves,

Thrown by the storm into the birdless air

I whose water-drunk carcass would not have been rescued

By the Monitors and the Hanseatic sailboats;

Free, smoking, topped with violet fog,

I who pierced the reddening sky like a wall,

Bearing, delicious jam for good poets

Lichens of sunlight and mucus of azure,

Who ran, spotted with small electric moons,

A wild plank, escorted by black seahorses,

When Julys beat down with blows of cudgels

The ultramarine skies with burning funnels;

I, who trembled, hearing at fifty leagues off

The moaning of the Behemoths in heat and the thick Maelstroms,

Eternal spinner of the blue immobility

I miss Europe with its ancient parapets!

I have seen sidereal archipelagos! and islands

Whose delirious skies are open to the sea-wanderer:

—Is it in these bottomless nights that you sleep and exile yourself,

Million golden birds, o future Vigor? –

But, in truth, I have wept too much! Dawns are heartbreaking.

Every moon is atrocious and every sun bitter.

Acrid love has swollen me with intoxicating torpor

O let my keel burst! O let me go into the sea!

If I want a water of Europe, it is the black

Cold puddle where in the sweet-smelling twilight

A squatting child full of sadness releases

A boat as fragile as a May butterfly.

No longer can I, bathed in your languor, o waves,

Follow in the wake of the cotton boats,

Nor cross through the pride of flags and flames,

Nor swim under the terrible eyes of prison ships.”

A reissue of Rimbaud’s highly influential work, with a new preface by Patti Smith and the original 1945 New Directions cover design by Alvin Lustig

In 2011 New Directions relaunched the long-celebrated bi-lingual edition of Rimbaud’s A Season In Hell and The Drunken Boat — a personal poem of damnation as well as a plea to be released from “the examination of his own depths.”

Rimbaud originally distributed A Season In Hell to friends as a self-published booklet, and soon afterward, at the age of nineteen, quit poetry altogether. New Directions’s edition was among the first to be published in the U.S., and it quickly became a classic. Rimbaud’s famous poem The Drunken Boat was subsequently added to the first paperbook printing. Allen Ginsberg proclaimed Arthur Rimbaud as “the first punk” — a visionary mentor to the Beats for both his recklessness and his fiery poetry.

Robert Mapplethorpe and Sam Wagstaff. Photo by Francesco Scavullo, 1974

Robert Mapplethorpe and Sam Wagstaff. Photo by Francesco Scavullo, 1974

Samuel Jones Wagstaff Jr. and Robert Mapplethorpe share the same birthday – November 4. But Sam Wagstaff was born 25 years earlier than Robert, in 1921

After seeing the exhibition The Painterly Photograph, 1890-1914 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1973 and meeting Robert Mapplethorpe in 1972, Wagstaff became convinced that photographs were the most unrecognized and, possibly, the most valuable works of art. He began selling his collection of paintings, using the proceeds to buy 19th-century American, British, and French photography. Then, influenced by Mapplethorpe, Wagstaff’s taste veered toward the daring, and he began to depart from established names in search of new talent. His collection was soon recognized as one of the finest private holdings in the United States.

PATHS THAT CROSS

Dedicated to the memory of Samuel J. Wagstaff.

Speak to me

Speak to me heart

I feel a needing

to bridge the clouds

Softly go

A way I wish to know

A way I wish to know

Oh you’ll ride

Surely dance

In a ring

Backwards and forwards

Those who seek

feel the glow

A glow we will all know

A glow we will all know

On that day

Filled with grace

And the heart’s communion

Steps we take

Steps we trace

Into the light of reunion

Paths that cross

will cross again

Paths that cross

will cross again

Speak to me

Speak to me shadow

I spin from the wheel

nothing at all

Save the need

the need to weave

A silk of souls

that whisper whisper

A silk of souls

that whispers to me

Speak to me heart

all things renew

hearts will mend

round the bend

Paths that cross

cross again

Paths that cross

will cross again

Rise up hold the reins

We’ll meet again I don’t know when

Hold tight bye bye

Paths that cross

will cross again

Paths that cross

Will cross again

Patti Smith

Dream of Life

1988

To listen to this song, please take a gander at The Genealogy of Style’s Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/pages/The-Genealogy-of-Style/597542157001228?ref=hl

At the Chelsea Hotel, Robert Mapplethorpe claimed (in his version), he met Patti Smith, who appeared in his open doorway looking for someone else, not Robert, whom she had never met. “I woke up,” Robert said, “and there was Patti. We recognized each other’s souls instantly. We had matching bodies. I had never met her, but I knew her.”

“Robert at first was too poor to live at the Chelsea Hotel, so he lived down the street, but he hung out in the Chelsea, cruising its corridors, picking up on the art-sex-and-drugs cachet of the address, trying to meet people who knew people.” Robert at the time was twenty years old and had been hustling Manhattan for four years. He was six years away from meeting art historian John McKendry, curator of photography at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, who bought Robert his first serious camera. Robert worked the Chelsea Hotel and the galleries by day the way, in the later, more successful, period in the late seventies, he worked clubs like Max’s Kansas City, The Saint, and the Mine Shaft by night. Those early days, he once told me, were hard and dark. Sometimes, he was able to afford the tab on a small room at the Chelsea Hotel on West Twenty-third Street. Sometimes, he retired to a dingy walk-up just down the street. In New York, one’s address is everything, and crashing the Chelsea, the notorious avant-garde enclave, gave Robert his first tangible sense of arrival.

The androgynous bodies took, according to Robert’s take, to a kind of Chelsea heterosexual bonding. They became a couple on the art-and-party circuit. They pooled their money to afford their nightly visits to Mickey Ruskin’s bistro at Park Avenue and Sixteenth Street, Max’s Kansas City, where sixties pop celebrated itself nightly. “I hated going there,” Robert said, “but I had to.”

At dawn, the young couple returned to the Chelsea. Robert supposedly had kicked a hole in the wall between his room and Patti’s. This instant suite was his first attempt at interior design. Robert needed Patti. He was alone. She was there. She nurtured him for several years. She was a writer and he was mad for the company of writers. She was a singer and he loved rock ‘n’ roll. The Chelsea Girls film had lasted three hours and fifteen minutes. Robert and Patti lasted longer. For a while, as a couple, they were chronologically correct, until they weren’t. Patti graduated to her own stardom, travels, and odalisques. One pop culture urban tale has Patti running off with playwright Sam Shepard, leaving Shepard’s writer/film actress wife, O-1an Jones (O-lan later became a theater legend, directing her experimental music and theater company, Overtone Industries). Another urban pop tale, told by porn star J. D. Slater, pairs Patti with the lead guitarist of MC-5, Fred Sonic Smith. Patti Smith herself can be the only one to tell the tales of her heart. Whatever her real private history, the true romance pop culture story is she never really left Robert, not for men, not for women, not for music, not for long, because she was more than his muse; she was his twin, his divine androgyne, and he was her photographer, the artist whose camera, with her, became positively Kirlian, capturing her spirit, her aura, her being.

His camera became their bond. “Patti is a genius.” Robert said that so often I began to understand that what he said about Patti he was projecting about himself as modestly as he could. His style was to reveal his personal self by indirection. (His professional self he revealed by edict.) Consequently, I never knew much about Patti, to whom I sometimes spoke on Robert’s phone calls from my home, because Robert used her as an emblem to talk about himself. When Edward Lucie-Smith met Robert and Patti, they were inmates at the Chelsea: spiritually, but not physically. “When I met him,” Edward said, “Robert was in one of his ‘broke’ phases, and the walk-up a few doors down the street was the place where he slept, if he ever did sleep, while he hung out at the Chelsea.” But Robert and Patti seemed avantly certifiable Chelsea Girls. Signs and omens were everywhere. Andy Warhol’s film was banned in Boston and Chicago. The “Chelsea Robert,” so enthralled by Warhol, was already on the trendy trajectory toward censorship.

Mapplethorpe: Assault with a Deadly Camera

Jack Fritscher

Virginia Woolf’s Bed. Photograph by Patti Smith, 2003

Virginia Woolf’s Bed. Photograph by Patti Smith, 2003

If God compel thee to this destiny,

To die alone, with none beside thy bed

To ruffle round with sobs thy last word said

And mark with tears the pulses ebb from thee,–

Pray then alone, ‘ O Christ, come tenderly !

By thy forsaken Sonship in the red

Drear wine-press,–by the wilderness out-spread,–

And the lone garden where thine agony

Fell bloody from thy brow,–by all of those

Permitted desolations, comfort mine !

No earthly friend being near me, interpose

No deathly angel ‘twixt my face aud thine,

But stoop Thyself to gather my life’s rose,

And smile away my mortal to Divine ! ‘

Elizabeth Barrett Browning

“The portraits he (Robert Mapplethorpe) shot by personal choice are a different take from the commercial portraits he did for cash. Let’s say Robert was good at perfecting people in the way that a good courtier perfects his patron, all the while keeping his cynicism cleverly coded even within the art piece.”

Edward Lucie-Smith

Gravity’s Rainbow is a 1973 novel by American writer Thomas Pynchon. The plot is complex, containing over 400 characters and involving many different threads of narrative which intersect and weave around one another. The recurring themes throughout the plot are the V-2 rocket, interplay between free will and Calvinistic predestination, breaking the cycle of nature, behavioral psychology, sexuality, paranoia and conspiracy theories such as the Phoebus cartel and the Illuminati.

The novel’s title declares its ambition and sets into resonance the oscillation between doom and freedom expressed throughout the book. An example of the superfluity of meanings characteristic of Pynchon’s work during his early years, Gravity’s Rainbow refers to:

*the parabolic trajectory of a V-2 rocket: the “rainbow-shaped” path created by the missile as it moves under the influence of gravity, subsequent to the engine’s deactivation;

the arc of the plot. Critics such as Weisenburger have found this trajectory to be cyclical or circular, like the true shape of a rainbow. This follows in the literary tradition of James Joyce‘s Finnegans Wake and Herman Melville‘s The Confidence-Man.

*The statistical pattern of impacts from rocket-bombs, invoked frequently in the novel by reference to the Poisson distribution.

*The introduction of randomness into the science of physics through the development of quantum mechanics, breaking the assumption of a deterministic universe.

*The animating effect of mortality on the human imagination.

Pynchon has brilliantly combined German political and cultural history with the mechanisms of paranoia to create an exceedingly complex work of art. The most important cultural figure in Gravity’s Rainbow is not Johann Wolfgang von Goethe or Richard Wagner, however, but Rainer Maria Rilke, Captain Blicero’s favorite poet. In a way, the book could be read as a serio-comic variation on Rilke’s Duino Elegies and their German Romantic echoes in Nazi culture. The “Elegies” begin with a cry: “Who, if I screamed, would hear me among the angelic orders? And even if one of them suddenly pressed me against his heart, I would fade in the strength of his stronger existence. For Beauty is nothing but the beginning of Terror that we’re still just able to bear, and why we adore it is because it serenely disdains to destroy us.”

These lines are hideously amplified in the first words of Pynchon’s novel: “A screaming comes across the sky. It has happened before, but there is nothing to compare it to now.” This sound is the scream of a V-2 rocket hitting London in 1944; it is also the screams of its victims and of those who have launched it. It is a scream of sado-masochistic orgasm, a coming together in death, and this too is an echo and development of the exalted and deathly imagery of Rilke’s poem.

Pynchon’s novel is strung between these first lines of the Duino Elegies and the last: “And we, who have always thought of happiness as climbing or ascending would feel the emotion that almost startles when a happy thing falls.” In Rilke, the “happy thing” is a sign of rebirth amidst the dead calm of winter: a “catkin” hanging from an empty hazel tree or the “rain that falls on the dark earth in early spring.” In Gravity’s Rainbow the “happy thing” that falls is a rocket like the one Blicero has launched toward London in the first pages of the book or the one also launched by Blicero that falls on the reader in the last words of the last page.

The arc of a rocket’s flight is Gravity’s Rainbow–a symbol not of God’s covenant with Noah that He will never again destroy all living things, nor of the inner instinctual wellsprings of life that will rise above the dark satanic mills in D.H. Lawrence‘s novel The Rainbow. Gravity’s Rainbow is a symbol of death: Pynchon’s characters “move forever under [the rocket]. . .as if it were the Rainbow, and they its children.”

Little Girl in the Big Ten, twentieth episode of The Simpsons‘ season 13 (May 12, 2002)

Little Girl in the Big Ten, twentieth episode of The Simpsons‘ season 13 (May 12, 2002)

Lisa: You’re reading Gravity’s Rainbow?

Brownie: Re-reading it.

My Mother the Carjacker, second episode of The Simpson’s season 15 (November 9, 2003)

My Mother the Carjacker, second episode of The Simpson’s season 15 (November 9, 2003)

Mona Simpson read Homer Gravity’s Rainbow as a good night story. After Homer started to sleep Mona said “Thomas Pynchon you are a tough read”, before she also started to sleep

Gravity’s Rainbow is a song by the British band Klaxons, from the album Myths of the Near Future (2007). Pat Benatar also released an album called Gravity’s Rainbow after reading Thomas Pynchon’s novel

Gravity’s Rainbow is a song by the British band Klaxons, from the album Myths of the Near Future (2007). Pat Benatar also released an album called Gravity’s Rainbow after reading Thomas Pynchon’s novel

The novel inspired the 1984 song Gravity’s Angel by Laurie Anderson. In her 2004 autobiographical performance The End of the Moon, Anderson said she once contacted Pynchon asking permission to adapt Gravity’s Rainbow as an opera. Pynchon replied that he would allow her to do so only if the opera was written for a single instrument: the banjo. Anderson said she took that as a polite “no.”

New York artist Zak Smith created a series of 760 drawings entitled, “One Picture for Every Page of Thomas Pynchon’s Novel Gravity’s Rainbow” (also known by the title Pictures of What Happens on Each Page of Thomas Pynchon’s Novel Gravity’s Rainbow)

“For one human being to love another, that is perhaps the most difficult of all our tasks;the ultimate, the last test and proof, the work for which all other work is but preparation.”

Rainer Maria Rilke

The inner sleeve of Patti Smith’s Wave (1979) includes this Rilke’s quote. Photo by Robert Mapplethorpe

The inner sleeve of Patti Smith’s Wave (1979) includes this Rilke’s quote. Photo by Robert Mapplethorpe

Total Eclipse is an intelligent look at the relationship between Rimbaud and Verlaine and shows considerable insight into the bourgeois and artistic societies of the period as well as a moving understanding of homosexuality.

Total Eclipse is an intelligent look at the relationship between Rimbaud and Verlaine and shows considerable insight into the bourgeois and artistic societies of the period as well as a moving understanding of homosexuality.

Christopher Hampton was only 22 when he wrote this play. He studied Rimbaud’s work at Oxford. Hampton became involved in the theatre while at that University where OUDS performed his play When Did You Last See My Mother?, about adolescent homosexuality, reflecting his own experiences at Lancing College. He is best known for his play based on the novel Les Liaisons dangereuses and the awarded film version Dangerous Liaisons (1988) and also more recently for writing the nominated screenplay for the film adaptation of Ian McEwan‘s Atonement.

Long before there were rock stars, there was rock star attitude, as displayed with spectacular insolence by the teen-age French poet Arthur Rimbaud. Rimbaud’s long shadow reaches not only into academe, where the writing he did before abandoning poetry at 20 is still much admired, but also into popular culture, where Bob Dylan, Jim Morrison or Patti Smith would not have been possible without him.

Total Eclipse is a 1995 film directed by Agnieszka Holland, based on a 1967 play by Christopher Hampton, who also wrote the screenplay. Based on letters and poems, it presents a historically accurate account of the passionate and violent relationship between the two 19th century French poets Paul Verlaine (David Thewlis) and Arthur Rimbaud (Leonardo DiCaprio), at a time of soaring creativity for both of them.

River Phoenix was originally attached to the project, but the part of Rimbaud went to Leonardo DiCaprio after Phoenix’s death. And John Malkovich was initially attached to play Verlaine, but pulled out. This movie has Leonardo Dicaprio’s first onscreen kiss (with costar David Thewlis).

“I can’t think of anybody like her. She is a national treasure, an icon, most people who see the film (Dream of Life) are like, ‘I thought she was just a rock singer’. They don’t realize that she’s the Arthur Rimbaud of our time. She’s a true artist. I wanted people to be inspired by her”

Steven Sebring

“William Burroughs was simultaneously old and young. Part sheriff, part gumshoe. All writer. He had a medicine chest he kept locked, but if you were in pain he would open it. He did not like to see his loved ones suffer. If you were infirm he would feed you. He’d appear at your door with a fish wrapped in newsprint and fry it up. He was inaccessible to a girl but I loved him anyway.

He camped in the Bunker with his typewriter, his shotgun, and his overcoat. From time to time he’d slip on his coat, saunter our way, and take his place at the table we reserved for him in front of the stage.”

Patti Smith

Just Kids

William Burroughs with Patti Smith at his Home, Franklin Street, NYC. Photo taken by Kate Simon on Patti Smith’s 29th birthday, 1975

William Burroughs with Patti Smith at his Home, Franklin Street, NYC. Photo taken by Kate Simon on Patti Smith’s 29th birthday, 1975

by Jade Reason

La vía del estilo

Art still has truth. Take refuge there.

Tales from Tinseltown...recording them now...I'll let you know when it's story time.

My Work My Art My Show - new school Sex and the City

All my words that are fit to print (and other's too!)

Making Life more Beautiful

Tulio Silva

Life, Leisure, Luxury

MYTHS AND HISTORIES OF A RELUCTANT BLOGGER

All my aimless thoughts, ideas, and ramblings, all packed into one site!

Meaning in Being. You be you.

Poetry, musings and sightings from where the country changes

Cooking is personalization.

Creativity is within us all