“Never regret thy fall,

O Icarus of the fearless flight

For the greatest tragedy of them all

Is never to feel the burning light.”

Oscar Wilde

*Photographs by Anthony Gayton

Icarus and Daedalus, Frederic Leighton,1869

“…Too venturous poesy O why essay

To pipe again of passion! fold thy wings

O’er daring Icarus and bid thy lay

Sleep hidden in the lyre’s silent strings,

Till thou hast found the old Castalian rill,

Or from the Lesbian waters plucked drowned Sappho’s golden quill!…”

Charmides (excerpt)

Oscar Wilde

1881

Frederic Leighton (1830-1896) was unmarried, left no diary, lived alone and always traveled alone, and has often been suspected of being secretly homosexual. However, later in life it is believed he may have loved his favorite female model, Dorothy Dene. Recently there was discovered some letters from the Italian painter Giovanni Costa, a friend of Leighton, to another English artist, in which Costa says that Leighton was “without his wife” at an exhibition, and later, “his wife keeps the reception rooms barred to us”. But Dene never lived with Leighton, and these references are confusing and may come from some sort of misunderstanding, or even playfulness. They do not suggest that Leighton himself referred to Dene as his “wife”.

However Leighton’s sexuality may have developed over his lifetime, earlier in life, Leighton’s first patron and intimate friend was Henry Greville, a wealthy aristocrat whom he met in Florence in 1856. Leighton’s letters to Greville are lost. Greville’s letters to Leighton are obviously love letters: he nicknamed Frederic “Fay” and called himself “Babbo” or “Bimbo” or “Babbino”; they often begin “My dear Boy” and end “Addio, carissimo.” He frequently addresses Leighton (who was 26 at the time) as “mon petit dernier” (“my little boy”). Greville’s letters reveal him to be an old sweetie or a silly old queen, depending on how you look at such things. He died in 1872. There is also a series of letters from Leighton to “Johnny,” John Hanson Walker, one of many young male artists whom he helped and befriended, of whom he made many studies. Greville often gave commissions to these young men through Leighton, and teases Leighton by calling them his “moddles”. The following letters were written by Greville to Leighton on his return from a trip to Paris soon after they met.

My dearest Fay, –

. . . [in response to criticism of his painting of Pan] It makes me so sick, all that cant about impropriety, but there is so much of it as to make the sale of “nude figures” very improbable, and therefore I hope you will turn your thoughts entirely to well-covered limbs, and paint no more Venuses for some time to come. . . . You dear boy, I am so glad you enjoy your Venice – which is all very pretty no doubt, but I hate stinks and fleas – and they abound there. I hate wobbling in a boat and walking in dirty alleys, so I don’t envy you at all. . . .

Love.

– Your old loving father,

H.London

September 29 [1856]

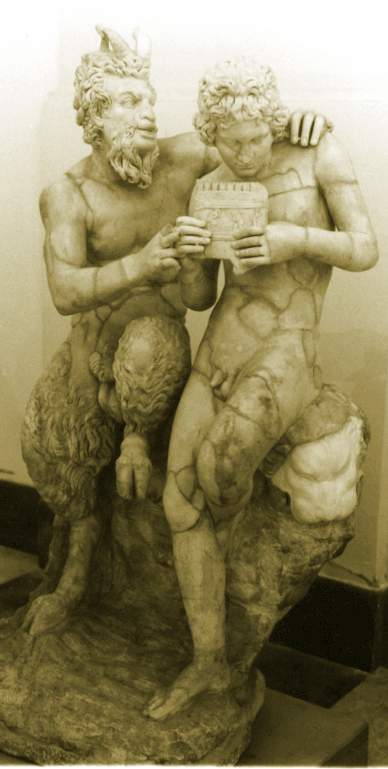

Pan, Frederic Leighton, 1855-6

Pan, Frederic Leighton, 1855-6

*Note:

Since the publication of Kenneth Dover‘s work Greek Homosexuality, the terms erastês and erômenos have been standard for the two pederastic roles. Both words derive from the Greek verb erô, erân, “to love”; see also eros. In Dover’s strict dichotomy, the erastês (ἐραστής, plural erastai) is the older lover, seen as the active or dominant partner, with the suffix -tês (-τής) denoting agency. Erastês should be distinguished from Greek paiderastês, which meant “lover of boys” usually with a negative connotation. The erastês himself might only be in his early twenties, and thus the age difference between the two lovers might be negligible.

The word erômenos, or “beloved” (ἐρώμενος, plural eromenoi), is the masculine form of the present passive participle from erô, viewed by Dover as the passive or subordinate partner.

“…His first touch of the earth went nigh to kill.

«Alas!» said he, «were I but always borne

Through dangerous winds, had but my footsteps worn

A path in hell, for ever would I bless

Horrors which nourish an uneasiness

For my own sullen conquering: to him

Who lives beyond earth’s boundary, grief is dim,

Sorrow is but a shadow: now I see

The grass; I feel the solid ground – Ah, me!

It is thy voice – divinest! Where? – who? who

Left thee so quiet on this bed of dew?

Behold upon this happy earth we are;

Let us ay love each other; let us fare

On forest-fruits, and never, never go

Among the abodes of mortals here below,

Or be by phantoms duped. O destiny!

Into a labyrinth now my soul would fly,

But with thy beauty will I deaden it.

Where didst thou melt too? By thee will I sit

For ever: let our fate stop here – a kid

I on this spot will offer: Pan will bid

Us live in peace, in love and peace among

His forest wildernesses. I have clung

To nothing, lov’d a nothing, nothing seen

Or felt but a great dream! O I have been

Presumptuous against love, against the sky,

Against all elements, against the tie

Of mortals each to each, against the blooms

Of flowers, rush of rivers, and the tombs

Of heroes gone! Against his proper glory

Has my own soul conspired: so my story

Will I to children utter, and repent.

There never liv’d a mortal man, who bent

His appetite beyond his natural sphere,

But starv’d and died…”

John Keats

Endymion (Book IV)

Excerpt

Pan teaching his eromenos, the shepherd Daphnis, to play the pipes.

Pan teaching his eromenos, the shepherd Daphnis, to play the pipes.

Second century AD Roman copy of Greek original c. 100 BC, found in Pompeii

I

O goat-foot God of Arcady!

This modern world is grey and old,

And what remains to us of thee?

No more the shepherd lads in glee

Throw apples at thy wattled fold,

O goat-foot God of Arcady!

Nor through the laurels can one see

Thy soft brown limbs, thy beard of gold,

And what remains to us of thee?

And dull and dead our Thames would be,

For here the winds are chill and cold,

O goat-foot God of Arcady!

Then keep the tomb of Helice,

Thine olive-woods, thy vine-clad wold,

And what remains to us of thee?

Though many an unsung elegy

Sleeps in the reeds our rivers hold,

O goat-foot God of Arcady!

Ah, what remains to us of thee?

II

Ah, leave the hills of Arcady,

Thy satyrs and their wanton play,

This modern world hath need of thee.

No nymph or Faun indeed have we,

For Faun and nymph are old and grey,

Ah, leave the hills of Arcady!

This is the land where liberty

Lit grave-browed Milton on his way,

This modern world hath need of thee!

A land of ancient chivalry

Where gentle Sidney saw the day,

Ah, leave the hills of Arcady!

This fierce sea-lion of the sea,

This England lacks some stronger lay,

This modern world hath need of thee!

The Painter of Pan’s Dionysiac woman, on the Kolonettenkrater in the Altes Museum, Berlin

The Painter of Pan’s Dionysiac woman, on the Kolonettenkrater in the Altes Museum, Berlin

Then blow some trumpet loud and free,

And give thine oaten pipe away,

Ah, leave the hills of Arcady!

This modern world hath need of thee!

Oscar Wilde

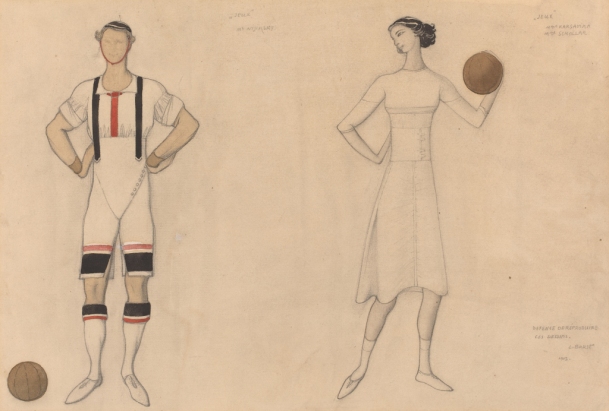

A minimalist, modern rendering by Léon Bakst for Costume Study for Jeux. Watercolor, graphite and black chalk on laid paper. Credit: National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

A minimalist, modern rendering by Léon Bakst for Costume Study for Jeux. Watercolor, graphite and black chalk on laid paper. Credit: National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Tamara Karsavina, Vaslav Nijinsky and Ludmilla Schollar in Jeux

Tamara Karsavina, Vaslav Nijinsky and Ludmilla Schollar in Jeux

Jeux (Games) is the last work for orchestra written by Claude Debussy. Described as a “poème dansé” (literally a “danced poem”), it was originally intended to accompany a ballet and was written for the Ballets Russes of Sergei Diaghilev to choreography by Vaslav Nijinsky.

Jeux premiered on 15 May 1913 at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, Paris, conducted by Pierre Monteux. The work was not well received and was soon eclipsed by Igor Stravinsky‘s The Rite of Spring, which was premiered two weeks later by Diaghilev’s company.

According to Nijinsky’s Diaries, made during the weeks before his psychological breakdown, Diaghilev intended the music to describe a homosexual encounter between three young men, and Nijinsky wanted to include an airplane crash. The final version of the story involved a man, two girls, and a game of tennis. The scenario was described to the audience at the premiere as follows:

“The scene is a garden at dusk; a tennis ball has been lost; a boy and two girls are searching for it. The artificial light of the large electric lamps shedding fantastic rays about them suggests the idea of childish games: they play hide and seek, they try to catch one another, they quarrel, they sulk without cause. The night is warm, the sky is bathed in pale light; they embrace. But the spell is broken by another tennis ball thrown in mischievously by an unknown hand. Surprised and alarmed, the boy and girls disappear into the nocturnal depths of the garden.”

Walter R. Roehmer as Pan, George Platt Lynes, circa 1939

Pan came out of the woods one day,—

His skin and his hair and his eyes were gray,

The gray of the moss of walls were they,—

And stood in the sun and looked his fill

At wooded valley and wooded hill.

He stood in the zephyr, pipes in hand,

On a height of naked pasture land;

In all the country he did command

He saw no smoke and he saw no roof.

That was well! and he stamped a hoof.

His heart knew peace, for none came here

To this lean feeding save once a year

Someone to salt the half-wild steer,

Or homespun children with clicking pails

Who see no little they tell no tales.

He tossed his pipes, too hard to teach

A new-world song, far out of reach,

For a sylvan sign that the blue jay’s screech

And the whimper of hawks beside the sun

Were music enough for him, for one.

Times were changed from what they were:

Such pipes kept less of power to stir

The fruited bough of the juniper

And the fragile bluets clustered there

Than the merest aimless breath of air.

They were pipes of pagan mirth,

And the world had found new terms of worth.

He laid him down on the sun-burned earth

And ravelled a flower and looked away—

Play? Play?—What should he play?

Robert Frost

A Boys’s Will

1915

In the exhibition, Mapplethorpe – Rodin the Museé Rodin brought together (in April 2014) the work of two artists – the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe and the sculptor Auguste Rodin. It presented 50 sculptures by Rodin and a collection of 102 photographs, revealing similarities in these two artists’ enduring themes and subjects. Mapplethorpe sought the perfect, sculptural form in his photography, whilst Rodin captured movement and accident in his work.

One of the curators, Judith Benhamou-Huet, commented:

‘This exhibition establishes an imaginary dialogue between Rodin and Mapplethorpe.

Mapplethorpe never made any reference to Auguste Rodin, but from 1979 – a period in which he uses a neo-classical vocabulary – his aim is obviously to create sculptures in photography. Through using the collection of the Rodin museum, myself and the other curators, Hélène Pinet and Hélène Marraud, found pieces where the photographer and the sculptor explore the same ideas.

They focus on detail, they use drapery to emphasize the drama of the shapes, and they place the models in special positions to emphasize the movement or sculptural aspect of their bodies.’

Lisa Lyon, Robert Mapplethorpe, 1982 / Torse fémenin assis sans tête dit du Victoria and Albert Museum (1910-14), Auguste Rodin

Lisa Lyon, Robert Mapplethorpe, 1982 / Torse fémenin assis sans tête dit du Victoria and Albert Museum (1910-14), Auguste Rodin

Javier, Robert Mapplethorpe, (date unknown)/ Buste de Hélène de Nostiz, Auguste Rodin, 1902

Javier, Robert Mapplethorpe, (date unknown)/ Buste de Hélène de Nostiz, Auguste Rodin, 1902

Orchid, Robert Mapplethorpe, 1985/ Iris, messagère des dieux, Auguste Rodin, 1891-93

Orchid, Robert Mapplethorpe, 1985/ Iris, messagère des dieux, Auguste Rodin, 1891-93

Feet, Robert Mapplethorpe, 1982/ Pied Gauche, Auguste Rodin, date unknown

Feet, Robert Mapplethorpe, 1982/ Pied Gauche, Auguste Rodin, date unknown

Lucinda Childs, Robert Mapplethorpe, 1985/ Assemblage: deux mains gauches, Auguste Rodin, (date unknown)

Lucinda Childs, Robert Mapplethorpe, 1985/ Assemblage: deux mains gauches, Auguste Rodin, (date unknown)

Bill T. Jones, Robert Mapplethorpe, 1985/ Génie funéraire, c. 1889

Bill T. Jones, Robert Mapplethorpe, 1985/ Génie funéraire, c. 1889

Michael Reed, Robert Mapplethorpe, 1987/ L´Homme qui marche, Auguste Rodin, c. 1899

Michael Reed, Robert Mapplethorpe, 1987/ L´Homme qui marche, Auguste Rodin, c. 1899

Robert Sherman, Robert Mapplethorpe, 1983/ Tête de la Luxure,Auguste Rodin, 1907

Robert Sherman, Robert Mapplethorpe, 1983/ Tête de la Luxure,Auguste Rodin, 1907

Ken Moody and Robert Sherman, Robert Mapplethorpe, 1984/ Tête de la doleur, Auguste Rodin, 1901-02

Ken Moody and Robert Sherman, Robert Mapplethorpe, 1984/ Tête de la doleur, Auguste Rodin, 1901-02

Source: Apollo Magazine

Sailors, by George Platt-Lynes

Sailors, by George Platt-Lynes

“Grave mouths of lions

Sinuous smiling of young crocodiles

Along the river’s water conveying millions

Isles of spice

How lovely he is, the son

Of the widowed queen

And the sailor

The handsome sailor abandons a siren,

Her widow’s lament at the south of the islet

It’s Diana of the barracks yard

Too short a dream

Dawn and lanterns barely extinguished

We are awakening

A tattered fanfare”

Jean Cocteau

Study from the ballet Orpheus, George Platt-Lynes, 1948-50. The thirty-minute ballet was created by choreographer George Balanchine in collaboration with composer Igor Stravinsky in Hollywood, California in 1947. Sets and costumes were created by Isamu Noguchi

Study from the ballet Orpheus, George Platt-Lynes, 1948-50. The thirty-minute ballet was created by choreographer George Balanchine in collaboration with composer Igor Stravinsky in Hollywood, California in 1947. Sets and costumes were created by Isamu Noguchi

Noguchi’s rendition of Orpheus’ lyre was adopted as and remains City Ballet’s official symbol.

Noguchi’s rendition of Orpheus’ lyre was adopted as and remains City Ballet’s official symbol.

“Ein Gott vermags. Wie aber, sag mir, soll

ein Mann ihm folgen durch die schmale Leier?

Sein Sinn ist Zwiespalt. An der Kreuzung zweier

Herzwege steht kein Tempel für Apoll.”

Rainer Maria Rilke

Die Sonette an Orpheus (Sonnets to Orpheus)

1922

__________________________________

“A God is able. But tell me, how shall

a man follow him through the narrow lyre?

His mind is divided. At the crossing of two

heart roads there is no temple for Apollo.”

AN DIE MUSIK

“Musik: Atem der Statuen. Vielleicht:

Stille der Bilder. Du Sprache wo Sprachen

enden. Du Zeit

die senkrecht steht auf der Richtung

vergehender Herzen.

Gefühle zu wem? O du der Gefühle

Wandlung in was?— in hörbare Landschaft.

Du Fremde: Musik. Du uns entwachsener

Herzraum. Innigstes unser,

das, uns übersteigend, hinausdrängt,—

heiliger Abschied:

da uns das Innre umsteht

als geübteste Ferne, als andre

Seite der Luft:

rein,

riesig

nicht mehr bewohnbar.”

Rainer Maria Rilke

1918

________________________________

TO MUSIC

“Music. The breathing of statues. Perhaps:

The silence of pictures. You, language where all

languages end. You, time

standing straight up out of the direction

of hearts passing on.

Feeling, for whom? O the transformation

of feeling into what?— into audible landscape.

Music: you stranger. Passion which

has outgrown us. Our inner most being,

transcending, driven out of us,—

holiest of departures:

inner worlds now

the most practiced of distances, as

the other side of thin air:

pure,

immense

no longer habitable.”

Couple saphique allongé, Auguste Rodin, c. 1897

Couple saphique allongé, Auguste Rodin, c. 1897

Rodin’s fascination for Sapphic couples, which he shared with Toulouse-Lautrec, Charles Baudelaire, Pierre Louÿs, Paul Verlaine and his predecessor Gustave Courbet, was evident in several of his drawings.

“I am sorry to have to ask you to allow me to mention what everybody declares unmentionable. My justification shall be that we may presently be saddled with the moral responsibility for monstrously severe punishments inflicted not only on persons who have corrupted children, but on others whose conduct, however nasty and ridiculous, has been perfectly within their admitted rights as individuals. To a fully occupied person in normal health, with due opportunities for a healthy social enjoyment, the mere idea of the subject of the threatened prosecutions is so expressively disagreeable as to appear unnatural. But everybody does not find it so. There are among us highly respected citizens who have been expelled from public schools for giving effect to the contrary opinion; and there are hundreds of others who might have been expelled on the same ground had they been found out. Greek philosophers, otherwise of unquestioned virtue, have differed with us on the point. So have soldiers, sailors, convicts, and in fact members of all communities deprived of intercourse with women. A whole series of Balzac’s novels turns upon attachments formed by galley slaves for one another – attachments which are represented as redeeming them from utter savagery. Women, from Sappho onwards, have shown that this appetite is not confined to one sex. Now, I do not believe myself to be the only man in England acquainted with these facts. I strongly protest against any journalist writing, as nine out of ten are at this moment dipping their pens to write, as if he had never heard of such things except as vague and sinister rumors concerning the most corrupt phases in the decadence of Babylon, Greece & Rome. I appeal now to the champions of individual rights to join me in a protest against a law by which two adult men can be sentenced to twenty years penal servitude for a private act, freely consented to & desired by both, which concerns themselves alone. There is absolutely no justification for the law except the old theological one of making the secular arm the instrument of God’s vengeance. It is a survival from that discarded system with its stonings and burnings; and it survives because it is so unpleasant that men are loath to meddle with it even with the object of getting rid of it, lest they should be suspected of acting in their personal interest. We are now free to face with the evil of our relic of Inquisition law, and of the moral cowardice, which prevents our getting rid of it. For my own part, I protest against the principle of the law under which the warrants have been issued; and I hope that no attempt will be made to enforce its outrageous penalties in the case of adult men.”

George Bernard Shaw

Letter sent to an editor of a Newspaper

1889

“The experience of loving, that now disappoints so many, can actually change and be transformed from the ground up into the building of a relationship between two human beings, not just a man and a woman. And this more authentic love will be evident in the utterly considerate, gentle, and clear manner of its binding and releasing. It will resemble what we now struggle to prepare: the love that consists of two solitudes which border, protect, and greet each other.”

Rainer Maria Rilke

Rome, May 14, 1904

Letters to a Young Poet

Total Eclipse is an intelligent look at the relationship between Rimbaud and Verlaine and shows considerable insight into the bourgeois and artistic societies of the period as well as a moving understanding of homosexuality.

Total Eclipse is an intelligent look at the relationship between Rimbaud and Verlaine and shows considerable insight into the bourgeois and artistic societies of the period as well as a moving understanding of homosexuality.

Christopher Hampton was only 22 when he wrote this play. He studied Rimbaud’s work at Oxford. Hampton became involved in the theatre while at that University where OUDS performed his play When Did You Last See My Mother?, about adolescent homosexuality, reflecting his own experiences at Lancing College. He is best known for his play based on the novel Les Liaisons dangereuses and the awarded film version Dangerous Liaisons (1988) and also more recently for writing the nominated screenplay for the film adaptation of Ian McEwan‘s Atonement.

Long before there were rock stars, there was rock star attitude, as displayed with spectacular insolence by the teen-age French poet Arthur Rimbaud. Rimbaud’s long shadow reaches not only into academe, where the writing he did before abandoning poetry at 20 is still much admired, but also into popular culture, where Bob Dylan, Jim Morrison or Patti Smith would not have been possible without him.

Total Eclipse is a 1995 film directed by Agnieszka Holland, based on a 1967 play by Christopher Hampton, who also wrote the screenplay. Based on letters and poems, it presents a historically accurate account of the passionate and violent relationship between the two 19th century French poets Paul Verlaine (David Thewlis) and Arthur Rimbaud (Leonardo DiCaprio), at a time of soaring creativity for both of them.

River Phoenix was originally attached to the project, but the part of Rimbaud went to Leonardo DiCaprio after Phoenix’s death. And John Malkovich was initially attached to play Verlaine, but pulled out. This movie has Leonardo Dicaprio’s first onscreen kiss (with costar David Thewlis).

by Jade Reason

La vía del estilo

Art still has truth. Take refuge there.

Tales from Tinseltown...recording them now...I'll let you know when it's story time.

My Work My Art My Show - new school Sex and the City

All my words that are fit to print (and other's too!)

Making Life more Beautiful

Tulio Silva

Life, Leisure, Luxury

MYTHS AND HISTORIES OF A RELUCTANT BLOGGER

All my aimless thoughts, ideas, and ramblings, all packed into one site!

Meaning in Being. You be you.

Poetry, musings and sightings from where the country changes

Cooking is personalization.

Creativity is within us all