The Mischief Makers (François Truffaut, 1956). This short film demonstrates already some examples for Truffaut’s “trademark tracking shots” and would “help define his style” as well as “set Truffaut on a path for his career”.

The Mischief Makers (François Truffaut, 1956). This short film demonstrates already some examples for Truffaut’s “trademark tracking shots” and would “help define his style” as well as “set Truffaut on a path for his career”.

“When I was shooting Les Mistons (The Mischief Makers), The 400 Blows already existed in my mind in the form of a short film, which was titled Antoine Runs Away.

I was disappointed by Les Mistons, or at least by its brevity. You see, I had come to reject the sort of film made up of several skits or sketches. So I preferred to leave Les Mistons as a short and to take my chances with a full-length film by spinning out the story of Antoine Runs Away. Of the five or six stories I had already outlined, this was my favorite, and it became The 400 Blows.

Antoine Runs Away was a twenty-minute sketch about a boy who plays hooky and, having no note to hand in as an excuse, makes up the story that his mother has died. His lie having been discovered, he does not dare go home and spends the night outdoors. I decided to develop this story with the help of Marcel Moussy, at the time a television writer whose shows for a program called If It Was You were very realistic and very successful. They always dealt with family or social problems. Moussy and I added to the beginning and the end of Antoine’s story until it became a kind of chronicle of a boy’s thirteenth year—of the awkward early teenaged years.

Notebook containing the first draft of the screenplay for The 400 Blows

Notebook containing the first draft of the screenplay for The 400 Blows

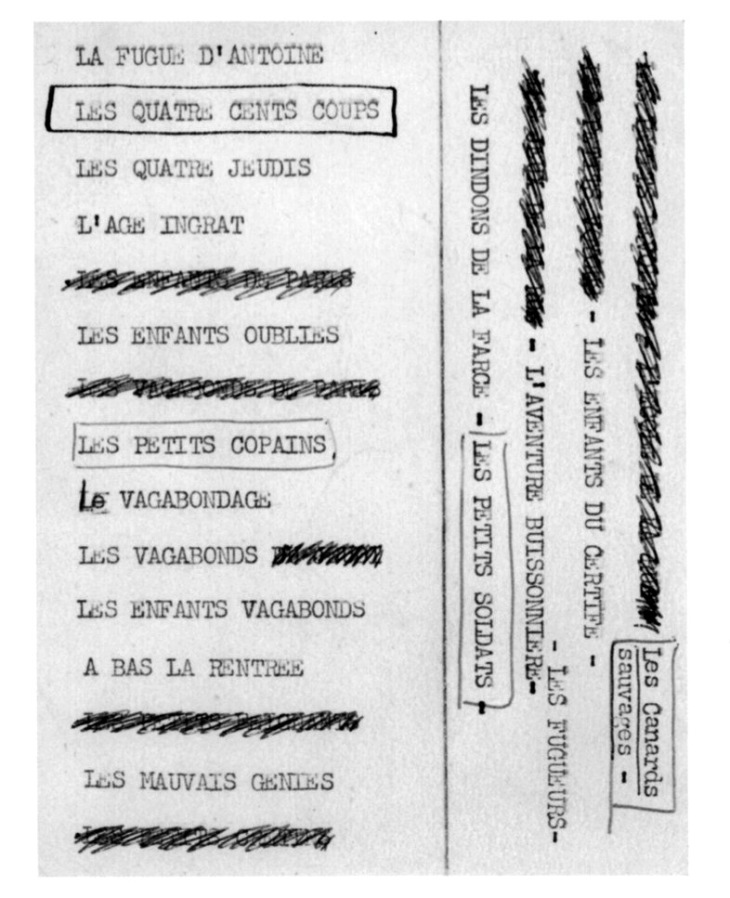

Truffaut searches for a title for his first feature film

Truffaut searches for a title for his first feature film

In fact, The 400 Blows became a rather pessimistic film. I can’t really say what the theme is—there is none, perhaps—but one central idea was to depict early adolescence as a difficult time of passage and not to fall into the usual nostalgia about “the good old days,” the salad days of youth. Because, for me in any event, childhood is a series of painful memories. Now, when I feel blue, I tell myself, “I’m an adult. I do as I please,” and that cheers me up right away. But then, childhood seemed like such a hard phase of life; you’re not allowed to make any mistakes. Making a mistake is a crime: you break a plate by mistake and it’s a real offense. That was my approach in The 400 Blows, using a relatively flexible script to leave room for improvisation, mostly provided by the actors. I was very happy in this respect with Jean-Pierre Léaud as Antoine, who was quite different from the original character I had imagined. And as we improvised more, the film became more pessimistic, then—in brief spurts, as a contrary reaction—so high-spirited that it almost became optimistic.

All I can say is that nothing in it is invented. What didn’t happen to me personally happened to people I know, to boys my age and even to people that I had read about in the papers. Nothing in The 400 Blows is pure fiction, then, but neither is the film a wholly autobiographical work.

There is indeed something anachronistic or composite-like about Antoine Doinel, but it’s difficult for me to define. I don’t really know who he is, except that he is a kind of mixture of Jean-Pierre Léaud and myself. He is a solitary type, a kind of loner who can make you laugh or smile about his misfortunes, and that allows me, through him, to touch on sad matters—but always with a light hand, without melodrama or sentimentality, because Doinel has a kind of courage about him. Yet he is the opposite of an exceptional or extraordinary character; what does differentiate him from average people, however, is that he never settles down into average situations. Doinel is only at ease in extreme situations: of profound disappointment and misery on the one hand, and total exhilaration and enthusiasm on the other. He also preserves a great deal of the childlike in his character, which means that you forget his real age. If he is twenty-eight, as Léaud was in 1972, you look at Doinel as if he were eighteen: a naïf, as it were, but a well-meaning one for all that.”

François Truffaut’s Last Interview

by Bert Cardullo