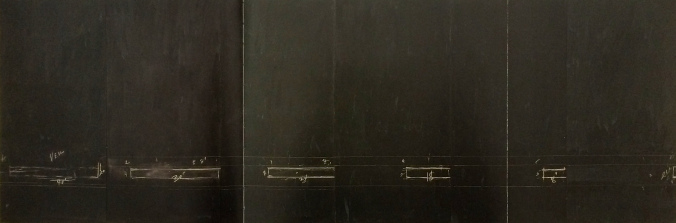

In the artist’s studio in Gaeta, a coastal town on the Mediterranean, works related to his Four Seasons series include details of Primavera (left) and Estate (right). The canvases, shown when still in progress in 1994, are nailed

In the artist’s studio in Gaeta, a coastal town on the Mediterranean, works related to his Four Seasons series include details of Primavera (left) and Estate (right). The canvases, shown when still in progress in 1994, are nailed

Cy Twombly enjoying local fare at a restaurant in Rome

Cy Twombly enjoying local fare at a restaurant in Rome

Another Twombly painting is propped against a wall in the house, where white tiles cover most of the floors

Another Twombly painting is propped against a wall in the house, where white tiles cover most of the floors

In the bright open Gaeta house, a second version of Inverno from Twombly’s Four Seasons series hangs against a wall for inspection. Books of poetry, postcards, acrylics and oils, crayons and pencils fill a table

In the bright open Gaeta house, a second version of Inverno from Twombly’s Four Seasons series hangs against a wall for inspection. Books of poetry, postcards, acrylics and oils, crayons and pencils fill a table

Twombly in the terraced garden outside the Gaeta house

Twombly in the terraced garden outside the Gaeta house

A still life in one of the house’s many rooms

A still life in one of the house’s many rooms

Found frames and French and American flags are propped against the walls in a hallway. Furniture is covered casually in a room behind

Found frames and French and American flags are propped against the walls in a hallway. Furniture is covered casually in a room behind

A Twombly sculpture and an antique stool and frame in another room in the apartment

A Twombly sculpture and an antique stool and frame in another room in the apartment

The artist in his vast, spare apartment on the via Monserrato in Rome, which house his collection of classical pieces

The artist in his vast, spare apartment on the via Monserrato in Rome, which house his collection of classical pieces

Photos by Bruce Weber

Text by Dodie Kazanjian

Vogue, 1994

The taxi doesn’t quite make it up the steep hill to Cy Twombly’s house in Gaeta. At the third hairpin turn we get out and walk the remaining 20 yards to a gray steel door embedded in a rough stone wall. Twombly has a little trouble opening it. Tall, lanky, dressed in rumpled white linen pants held up by blue suspenders, he looks more like a provincial winegrower than a famous artist. The door grates on its hinges, and we’re inside a paradise of thick white walls, terraces, ceramic tile floors, and cool interconnecting rooms bare of furniture except for a few striking pieces—bleached Louis XV chairs, a long table piled high with books, blue-and-white fabrics, ornate empty picture frames, Twombly paintings leaning against the walls, and one or two of his little-known, gawky, white-painted sculptures. Twombly throws back the shutters in each room, flooding the house with light and opening up dazzling vistas of the seaside town and the blue Mediterranean.

On the train down from Rome this morning Twombly started telling me and my husband, an old friend of his, about the town as soon as it came into view around the shoulder of a mountain. “Hadrian had a villa here,” he said. “Cicero is buried here, and so is the Roman general who founded Lyon. Catullus had friends here. It was kind of a summer art colony, like East Hampton, but not anymore—that was 2,000 years ago. Gaeta was the name of Aeneas’s wet nurse. She was with him on his return from Troy, and she died here, so he named the place after her. I believe that. Nobody could make that up.” Twombly is full of history, which he relays in the accents of his Virginia childhood. Even his Italian comes out that way—when he says si, si, which he does a lot, it has a southern drawl to it.

Gaeta, 60 miles north of Naples, is where Twombly has done most of his painting in the last few years. Tacked to the wall in the high-ceilinged room he uses as his studio is a large vertical canvas, more than ten feet tall. Titled Summer, it is the last of a series on the four seasons, which will be shown at the Twombly retrospective that opens at the Museum of Modern Art in New York this month and then travels to Houston, Los Angeles, and Berlin. Autumn, Winter, and Spring (in that order) were finished months ago and have already been shipped to the museum. But “I’m having a real bad time with Summer,” he had told me several times when I spoke with him by telephone from New York. The painting is still unfinished, and Twombly is not happy about letting us see it. When we start asking questions about the Four Seasons, he bristles. “It’s not Four Seasons,” he says. “That sounds like the Four Seasons Hotel. I think of them as Quattro Stagioni. Summer isn’t finished yet, as I told you, and that’s all I’m going to say about that. It’s absurd to talk about paintings that you haven’t finished.”

Cy Twombly is the great outsider of contemporary art. In 1957, at the precise moment when the main energy of the art world seemed to have taken up permanent residence in New York, Twombly moved to Rome. Two years later, he married Tatiana Franchetti, a talented portrait painter from a wealthy and aristocratic Italian family, and he has lived in Italy, more or less, ever since. While his fellow southerners Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns were using popular imagery and mundane objects to blaze the trails that would lead to Pop and Minimal art, Twombly chose a different direction entirely. His would lead back through European art and literature to the ancient world of classical mythology, of gods and heroes and the great poetic traditions of the Mediterranean, which in his paintings merges indistinguishably with the modern urban street culture of graffiti, sexual imagery, and raw sensation. His work seems to exist in another time zone.

But Twombly’s work has never been easy to like. The scribbles, smears, blots, and seemingly random markings of his intensely personal style have often evoked the kind of philistine response that says, “My kid could do better than that.” Artists love his work, but will the public come to see it at MoMA? Twombly is definitely “an acquired taste, even within the art world,” says curator Mark Rosenthal, who tried to do a Twombly retrospective a few years ago while at the Philadelphia Museum of Art—Twombly initially agreed but changed his mind in midstream. The National Endowment for the Arts refused to give a grant to the current show, and the Modern was unable to line up a major corporate sponsor.

Twombly is famously difficult and famously elusive, and this has not made his work any easier to see. Ever since the disastrous 1964 show of his Commodus paintings at the Castelli Gallery in New York—their fervid painterliness seemed out of step with the hard-edged commercial imagery of Pop Art, then in ascendance, and nothing was sold—he has shown infrequently in this country. “Cy just evaporated,” according to Leo Castelli. Twombly has avoided exclusive commitments with any dealer, preferring to control the distribution of his rare new paintings through one or two close associates, and much of his major work is in European, not American, collections.

Twombly goes off to another part of the house, leaving us alone with the painting. In addition to Summer, there are three other unstretched canvases nailed to the walls of his studio, part of a second series on the same Quattro Stagioni theme. Twombly often paints a subject more than once: There are four versions of Leda and the Swan, two of the School of Athens, two of Birth of Venus.) His worktables are covered with oil crayons; pencils; tubes of pigment; postcard reproductions of boats and marine scenes; a big Manet art book open to a page that shows a boat painting; stacks of other art books (Ensor, Whistler, Turner); and a book of modern Greek poems in translation, turned to George Seferis’s Three Secret Poems. Several lines of one stanza have been altered by Twombly, with some words inked out. A section of the edited and spliced poem (with a few new words added by Twombly) is written on the canvas of Summer, in Twombly’s inimitable, childish scrawl:

“the shard of white . . .

trembling with white light

with white flat sea

distant in memory

between the deluge of life

our dearest, our white youth

our white, our snow white youth

that is infinity . . .”

Twombly’s paintings often seem to be as much written as painted. His spindly, meandering letters and words can evoke memory and emotion with the power of Chinese calligraphy, but their effect is never literary—the words work within the visual field of a master painter. And Twombly has never painted better than in his Four Seasons series. The paint is luscious, active, full of violent movement. The image of a spectral boat with oars, which recurs throughout the series, is gray in Summer, but hot yellows and reds predominate—sun colors, on a mostly white or unpainted ground. The cut-up lines of poetry appear and disappear, run down one side of the canvas, sometimes partially smudged or painted over. It’s vintage Twombly, aggressive, hesitant, tough, nervous, scatological, poetic, complex, playful, ancient, up-to-the-minute, intensely personal, and grand—a bundle of contradictory impulses that miraculously work together.

Comparisons are inevitable between Twombly’s Four Seasons and Jasper Johns’s four paintings on the same theme, which were done between 1985 and 1986. Twombly had been thinking about the seasons theme for a long time. He played with it in earlier works, such as the 1961 Empire of Flora and the four-panel 1977 Bacchanalia, and in recent years, as the main emphasis in his work has shifted from history and myth to nature, he became drawn to what is, after all, one of the great themes of European art. “All of Jasper’s seasons look like winter,” Twombly says with a sly chuckle. “Mine all look like summer.”

That may have been the way they started, but it’s not true any longer. Autunno is saturated with the deep reds and throbbing purples of the wine harvest; it has the word Silenus, the wine god, written across it, and, near the right edge, the words pure wild sex. This is a long way from the stately black-and-yellow Inverno, and the raspy yellows and reds of Primavera, a raw rite of spring, with jagged boat shapes up and down the middle. The day after he finally finished the last in the series, Twombly told me, “My head is completely burning up. All I’m doing is seeing yellow. I wake up in the morning, and the white walls look yellow. I had a great deal of trouble with Summer. At a certain point I was ready to throw in the brush. But I got crazy in a good way here.” By this time, however, the painting my husband and I had seen no longer existed. Twombly had decided to start over on a fresh canvas. I went to see it the day it arrived in New York. You could still smell the paint. It was simpler than the previous one, and much more liquid, wet and runny, with molten streaks of red and yellow and orange. “High on light” was scrawled on the left side in red, “how the dizziness/slipped away/like a fish in the/sea.”

Two days before the trip to Gaeta, in Twombly’s apartment on the via Monserrato in Rome, we had seen a quartet of paintings on the four seasons by an anonymous seventeenth-century Italian mannerist, part of Twombly’s wide-ranging and eccentric collection. Also two huge dark eighteenth-century landscapes by John Wootton, whom Twombly described as the English artist who introduced the work of Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin to England. “I look at a lot of artists,’ ” he says. “I’m inspired by—I suppose I shouldn’t say ‘inspired,’ but it’s not really influenced. I am inspired. Art comes from art.” Classical busts of Apollo, Venus, Marcus Aurelius, and other worthies stand on pedestals in the rather grandiose, white-walled rooms of the Rome apartment, where the furniture looks as though it never gets much use.

Twombly started buying antiquities on his first visit to Rome, with Robert Rauschenberg, in 1952. “He spent my half of our grant on Roman sculpture,” according to Rauschenberg. “So I had to go off and get a job with Atlas Construction in Casablanca.” Twombly quit buying classical antiquities a few years ago. “New York decorators started putting a classical torso in every room, and it became impossible,” he says. But when we walk with him in Rome, he constantly stops to look at objects in shop windows—a malachite clock, a tiny piano (“It must have been Mozart’s first”), a miniature sarcophagus with a lapis top (“It’s not very good lapis. The best lapis comes from Afghanistan”). His eagle eye for quality deceives some people into thinking of him as a great decorator, but his various domestic interiors, striking as they are, have almost nothing to do with decoration, or with comfort, either. They all have the transient look of spaces that are used primarily for work.

When Twombly and Rauschenberg were together at Black Mountain College, they were exposed to what their fellow student Francine du Plessix Gray describes as a “grab bag” approach to world culture. “We were reading Ezra Pound’s Guide to Kulchur and then Virgil because Pound tells you to read Virgil and Fenollosa on Japanese art and Dostoyevsky’s Notes from the Underground and Leo Frobenius on African rock painting and Pausanias’s Description of Greece. This sort of nativist American grab-bag attitude reminds me very much of the cultural map implied in Cy’s paintings.”

It might also be said to describe the kind of restless life that Twombly has chosen to lead. For years now, he has spent very little time in Rome. He owns a sixteenth-century villa in Bassano, near the gardens of Bomarzo, an hour north of Rome. Many of his paintings and drawings have been done during temporary stays in other places he likes—Sperlonga, Mykonos, the Seychelles, Robert Rauschenberg’s house on Captiva Island in Florida, an Italian friend’s villa in Bolsena. He travels all the time, sometimes with his wife, Tatiana, who nevertheless leads a highly independent life of her own, and whose hobby is collecting old rosebushes—she was on a rose hunt in Turkistan at the time of our visit to Gaeta. (Their 34-year-old son, Alessandro, who is also a painter, collects iris tubers.) “I fall in love with places,” Twombly tells us. He fell in love with Paris a few years back, rented and furnished an apartment there, but never stayed in it; he found he preferred his circular corner room at the Left Bank Hôtel de la Louisiane. “Simone de Beauvoir lived there. Sartre, too, but of course he went home to mama every night, like a good French writer.”

Last year he rediscovered Lexington, Virginia, where he grew up. He recently bought a house in the town and now spends several months a year there. “I’m like an old dog who’s come home to die. I see people I grew up with, but I can’t talk about old times with them. I can’t remember any of that. It’s not a nostalgic trip for me.” His father, a coach and, later, athletic director at Washington and Lee University there, had acquired the nickname Cy (after the legendary pitcher Cy Young) when he pitched for the Chicago White Sox one summer. He passed it on to his only son, who showed no enthusiasm for organized athletics. Cy’s parents came from old-line New England families—as a boy, he used to visit his grandparents in Bar Harbor, Boston, and Palm Beach—and a sense of that old American aristocracy is never far from the surface of his laconic, laid-back personality. “When he moved to Italy, I think he was recovering that aristocracy that he always felt by nature,” says Rauschenberg. “I couldn’t forget that he couldn’t forget it.”

Twombly has always been a loner. Unlike most successful artists these days, he has no studio assistants and wants nobody around when he’s working. This sometimes leads to odd working habits. “One Twombly I really love is called Untitled, 1958,” says cult-film director John Waters. “It’s all on the very bottom of the painting. It looks like the artist climbed up a ladder, but it was hung so high he could only reach the very bottom. He barely managed a scribble, hardly a mark. And then he fell off the ladder and died. I love art that does that, that makes people crazy.” Waters wasn’t just fantasizing, as it turns out. “I just finished a big painting, sixteen meters long and four meters high, that I’ve been working on, off and on, for ten years,” Twombly tells me. “It’s hard for me to get up on a ladder because I’m all alone in the studio. I could fall off and be lying on the floor for days. So most things happen at the bottom of the painting.”

Twombly answers his own phone—when and if he feels like it. Friends used to reach him by letting his number ring twice, hanging up, and dialing again, but that system is no longer operative. He hates being interviewed or photographed, rules out tape recorders or notebooks, and balks at any sort of direct questions about his life or his painting. (He agreed to teach a philosophy seminar at Washington and Lee last spring and chose his own subject: the idea of metamorphosis. But he quit after one session because the students “asked too many questions.”) He’s definitive in his likes and dislikes—good, unpretentious trattorias over four-star showplaces; espresso in a glass (“It tastes much smoother than in porcelain, like tea tastes better from a china than a silver pot”); shirts and underpants from Brooks Brothers; white linen pants from “Banana” (he means Banana Republic); Bass loafers because “they’re the only ones who make the nonshiny kind”; a 1940s white double-breasted whipcord jacket that he found at a thrift shop. He reads for two or three hours every day in his eclectic fashion—history, poetry, travel books, Walter Pater’s essays, Robert Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy. He’s never liked the process of printmaking, “because you have to work with all those other people.” He doesn’t want to think of himself as a professional painter (the aristocratic prejudice again), and he works only when he feels like it—sometimes months will go by when he doesn’t paint. He hates to make plans or schedules, moves from place to place on impulse, doesn’t always show up when he’s invited somewhere. “Cy says he’ll be there in half an hour,” Rauschenberg quips, “but he doesn’t say which month.”

Twombly has always been astute about placing his work, and now it is about to become much more visible in the United States, and not just at the Modern. Fifty Days at lliam, his ten-part painting on the theme of the Trojan War, has been on permanent display since 1989, in a space of its own, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. (Cy is aware that he misspelled Iliam—it should be Ilium. He laughs off the story that he once said, “My painting isn’t getting better, but my spelling is.”) The Menil Collection in Houston is building a special addition that will be, in effect, a one-man Twombly museum, although Twombly, who designed the floor plan in collaboration with architect Renzo Piano, prefers to call it a gallery; the inauguration will be next February, when MoMA’s Twombly show comes to Houston. The Dia Center for the Arts in New York, which has a large collection of Twombly’s work, plans to install most of it in 1996 in a newly created space on West Twenty-second Street. Twombly has been generous with these institutions because they are so obviously dedicated to his work, but there is no doubt who calls the shots and controls the way his work will be seen. Asked whom to go to for a new Twombly painting, he replies, “I have them.”

Twombly is showing us his garden in Gaeta, a terraced landscape on the hill above the house. It’s a series of what he calls stanze segrete, “secret rooms,” each defined by a different tree—pleached lindens, lemon trees, square-and-cone-shaped laurels, orange trees—with hedges of olive and laurel. It’s a green garden with no flowers. “I hate roses,” he says. “Don’t you? It’s all right if you can hide them in a cutting garden, but I think a rose garden is the height of ick.” Each “room” has stunning views of the sea and of the two ancient castles on the next hill. The red-tile roofs of his own house are directly below. “I love that,” he drawls. “It looks like an Arab village.” He is less pleased with the church next door. “It’s a hideous nineteenth- century Victorian church,” he says, “where everybody wants to get married.”

We walk down the hill for lunch at his favorite local trattoria. It’s full of large families enjoying Sunday dinner. “Sit over there,” he tells me, “so you won’t have to look at the babies.” Kids run in and out and between the tables, getting into fights. “Alessandro was such a good child,” Twombly says ruefully. “If you sent him out to play, he’d send back a note saying, ‘I’m in the garden.’ ” I make the mistake of trying to get him to talk about his New England family (without asking any direct questions), and the undercurrent of irritation that has been building up in him suddenly erupts. “I swear if I had to do this over again, I would just do the paintings and never show them. And then after I’m dead, they could talk about them all they want. I’m just not interested in myself that way. I was brought up to think you don’t talk about yourself. I hate all this. Why should I have to talk about the paintings. I do them, isn’t that enough?”

The storm passes, and we finish lunch. Walking through town afterward, along the seawall, Twombly is friendly and conversational, pointing out the thirteenth-century campanile with its Moorish inlaid tiles and saying how much better the town would look if the houses were all painted white. Twombly has made the ancient world of the Mediterranean his own. He likes to say that he has no sense of time. “Sometimes when I’m writing the date on a letter, I have to ask what year it is.” He talks about the illustrated books he wants to do after he gets through the “anguish” of the Modern show. Some years ago, he did illustrations for the Odes of Horace and for Edmund Spenser’s Shepheardes Calender. “I like bucolic poetry,” he says. “Theocritus, Virgil. I’m from an agrarian part of the country. Although I wouldn’t do it if I was in America. When I used to spend time in Bassano, you could still see shepherds tending flocks of goats. Once I actually saw one throw himself down under a tree and play a flute. It still lives here, that Mediterranean world. And nothing that’s living is old to me.”

Cy Twombly photographed by Robert Rauschenberg, circa 1953

Cy Twombly photographed by Robert Rauschenberg, circa 1953 Treatise on the Veil (First Version), Cy Twombly, 1968.

Treatise on the Veil (First Version), Cy Twombly, 1968. Pierre Henry using induction coils to control sound spatially.

Pierre Henry using induction coils to control sound spatially. Veil of Orpheus, Cy Twombly, 1968

Veil of Orpheus, Cy Twombly, 1968