“I like Alexander McQueen’s work a lot: he’s always pushing boundaries, and he’s rough around the edges. The idea of this hard-edged genius being interviewed by his mum, by the person that spawned him, really appealed to me.”

Sam Taylor-Woods

Joyce McQueen: I would have liked to have invited the late Peter Ustinov for dinner, for his wit and conversation. Who would you like as a dinner guest and why?

Alexander McQueen: What, if I could choose anyone?

JM: Anyone in the world.

AM: Elizabeth I …

JM: Why would you want Elizabeth I? The history maybe?

AM: ‘Cause she’s an anarchist.

JM: She’s an anarchist?

AM: She was an anarchist, yeah. Do you want to have a bit of debate on this?

JM: Well, not at the moment, no.

AM: Because, y’know, she kind of founded the Church of England under her father, with all the upheaval from the French and the Scottish …

JM: Who are your other ones?

AM: Jesus of Nazareth, to check if he really exists, and it’s not just we’ve been reading some Peter Pan book for the past 2,000 years. Or Mel Gibson, to be there if Jesus wasn’t true.

JM: If you could live and work as a designer in any era, which one would it be?

AM: Any time? Future as well?

JM: Future as well. But particularly the past.

AM: Let’s stick to the past then. I’m thinking cavemen and loincloths.

JM: What about Tudors and Stuarts?

AM: Er … I’m answering the questions! Most probably …

JM: What about –

AM: I’m thinking ! Fifteenth-century Flemish, Netherlands. My favourite part of art. Because of the colours, because of the sympathetic way they approached life.

JM: Simplicity, you mean.

AM: I’m not going to get into a big art debate with you.

JM: No, I’m trying to get to the bottom of why you like that.

AM: ‘Cause I think they were very modern for their times, in that period and in that part of the world.

JM: You spend as much time as possible in your beautiful cottage in the country. Do you find that the inspiration you get down there features in your work?

AM: I don’t find inspiration there – it gives me a peace of mind, Mum. Solitude, and a blank canvas to work from, instead of the distractions of the concrete jungle.

JM: Right. So it does inspire you in some ways then.

AM: Not technically. Not country life or bobbing rabbits. It’s the peace and quiet.

JM: As you know, I’m a Simply Red and Elton John fan. Who are your favourite artists?

AM: As in singers?

JM: Yeah, well, y’know, groups, whatever. Because at one time, you were very much into classical music.

AM: Beyoncé. No, I’m only joking.

JM: He was about, what, 15. I know because I’ve still got them at home.

AM: I think composers. People like Michael Nyman, who compose an original piece of music – believe it or not, the artists today are inspired by people like Michael Nyman and Philip Glass, who come up with unusual sounds.

JM: I know, I know, that’s where pop music comes from …

AM: Nah, it’s like the architect who designed the Gherkin [Norman Foster and his Swiss Re tower in London] inspires people, or Alexander McQueen does a collection that inspires other people to do different things and move things forward. Rap music’s been around for too long now to be inspirational. The words are, but the music isn’t.

JM: You haven’t given me an answer there. You haven’t come out with a group.

AM: I have – Philip Glass and Michael Nyman.

JM: All right, then. I’ll ask another question. You have traveled extensively around the world but still have not been to the Isle of Skye, which is the root of your McQueen history. Will you ever visit that area?

AM: Mmm … yes.

JM: In the near future?

AM: Yes.

JM: Right. And that follows on to my next question: what do your Scottish roots mean to you?

AM: Everything.

JM: Well, where do I come in?

AM: [laughs] Oh you’re from the Forest of Dean, yeah. What do you mean, where do you come in?

JM: Well, your Scottish roots mean a lot to you. So where does your mother’s side come in?

AM: What does my mother’s side, the Welsh side, mean to me?

JM: I’m not Welsh! I’m Norman!

AM: All right, Norman! Where does this Norman come from?

JM: Well they come from Viking stock.

AM: That answers a lot for an awful lot of people, I think. I feel more Scottish than Norman.

JM: You recently got your deep-sea diving certificate, didn’t you?

AM: Yeah, underwater diving.

JM: Well, two of my family discovered the wreck of the Marie Rose, deep-sea divers. Just explains that you’ve taken up deep-sea diving as well. It’s a follow-on really, isn’t it?

AM: So from the McQueen side I’ve got anarchy, and my mum’s side, underwater diving.

JM: The calm part. You are often described as an architect of clothing, and I know that you have a keen interest in architecture. What is the most breathtaking building you’ve ever seen?

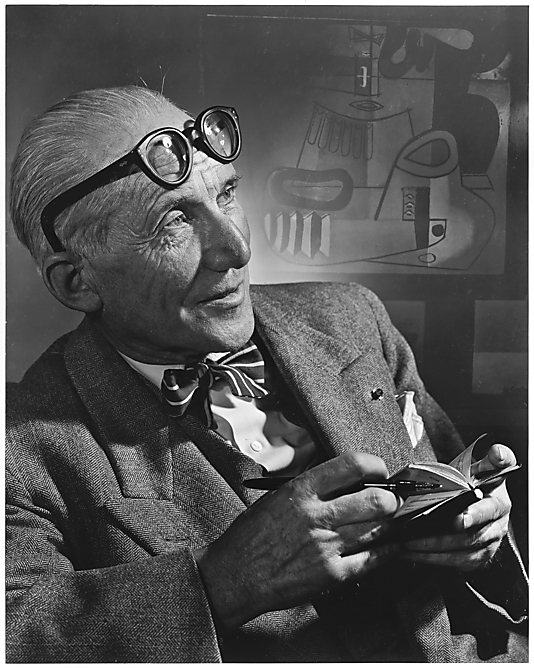

AM: Ronchamps, by Le Corbusier.

JM: What do you think of the modern buildings in London?

AM: I love the Gherkin.

JM: You do?

AM: I think it’s fantastic.

JM: But you don’t like any of the old architecture in London?

AM: Well, yeah, but it’s not as nice as it is in Italy or Paris.

JM: If you hadn’t trained on Savile Row, how would you have entered the fashion industry?

AM: I’d have slept my way there.

JM: Or, I don’t know …

AM: Other ways. I’d have found other ways of getting into it.

JM: Do you look at something else and say, “I could have done that as well”?

AM: Photo-journalism. It’s art for the modern times. I think it captures a moment in time that is spontaneous and that reflects where we are. The one I couldn’t have done is be an architect, because I don’t have the brain capacity or the patience.

JM: No, you haven’t got the patience, have you? You mix with VIPs, celebrities, aristocracy … How does coming home and being the baby of the family make you feel?

AM: I’m never fazed by it, because whenever I get home, Dad will always ask me to make him a cup of tea. So it’s just normal.

JM: If you were prime minister or in government, what policies would you implement to make the UK a better place to live?

AM: More politically correct police officers on the streets. And more focus on the north of England instead of just the south, on not so developed parts of the country.

JM: What do you mean, “politically correct police”?

AM: Well, not homophobic police, not racist police, you know? The police need to come down to street level.

JM: Success has brought you financial security. But if you lost it all tomorrow, what would be the first thing you would do?

AM: Sleep. I’d be pleased.

JM: I said you’d go on holiday.

AM: What with? I’d lost it all!

JM: When you received your CBE last October, you told me and Dad that you locked eyes with the Queen and it was like falling in love. What was it about her presence that captivated you?

AM: I made a pact with myself that I wasn’t going to look into her eyes.

JM: But you did.

AM: I did. There was a simultaneous lock, and she started laughing, and I started laughing …

JM: It was a nice moment, wasn’t it?

AM: It was. We caught it on camera where we’re both laughing at each other. She asked a question, “How long have you been a fashion designer?” and I said, “A few years, m’lady.” I wasn’t thinking straight – because I’d hardly had any sleep.

JM: You were nervous.

AM: I was really tired. And I looked into her eyes, it was like when you see someone across the room on a dance floor and you think, “Whoa!” It was like when I looked into her eyes, it was obvious that she had her fair share of shit going on. I felt sorry for her. I’ve said a lot of stuff about the Queen in the past – she sits on her arse and she gets paid an awful lot of money for it – but for that instant I had a bit of compassion for her. So I came away feeling humbled by the situation, when I wouldn’t have even been in the situation if it wasn’t for you.

JM: I thought it was a great honour.

AM: I didn’t want to do it.

JM: It was an honour for you …

AM: Yeah, but I had my views on what it stands for.

JM: What is your most terrifying fear?

AM: Dying before you.

JM: Thank you, son. What makes you proud?

AM: You.

JM: Why?

AM: No, no, ask the next one: “What makes you furious?” You! [laughs]

JM: No, go on, what makes you proud?

AM: When things go right, when the collection goes right, when everyone else in the company’s proud.

JM: What makes you furious?

AM: Bigotry.

JM: What makes your heart miss a beat?

AM: Love.

JM: Love for children? Love for adults? Love for animals?

AM: Falling in love.