F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald

F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald

While a teenager, Francis Scott Fitzgerald was collecting ideas about the goings on in West Egg and not just those of the community but those of a specific man: W. Gould Brokaw, a now-forgotten Long Island socialite, playboy and gentleman automobile racer. He literally could not escape his shadow.

W. Gould Brokaw

W. Gould Brokaw

Brokaw was the son of hugely successful New York clothier Vail Brokaw of Brokaw Brothers, and grandson of a railroad tycoon; he inherited a fortune of around $4.5 million and never needed to do anything in particular for work. His circle of friends was the cream of New York society: Astors, Whitneys, Guggenheims, Vanderbilts, Goulds, Morgans, all of them interested in speed, whether horses, greyhounds, yachts or cars. Brokaw was an elder statesman for that set of young millionaires, having been born a decade or more before most, in 1863. In later legal proceedings–of which there were oh so many, he was described as “a rich and fashionable clubman.”

According to Some Sort of Grandeur, Matthew Bruccoli’s biography of Francis Scott Fitzgerald, the character Jay Gatsby is based on the bootlegger and earlier World War I officer Max Gerlach. In the 1920s, when Gerlach knew the Fitzgeralds, he operated as a bootlegger and allegedly kept Fitzgerald topped off with booze. Born in Yonkers as Max A. Stark (or possibly Max A. Stork), he claimed direct German ancestry and went by the names of Max Stark Gerlach and Max von Gerlach later in life (his gravestone reads Max Stork Gerlach). Nevertheless, Gatsby is a composite, as are all Fitzgerald’s characters, and there’s a certain amount of Scottie himself in Jay.

Robert Evans and Ali MacGraw

Robert Evans and Ali MacGraw

About the filming adaption of The Great Gatsby directed by Jack Clayton in 1974, it was originally conceived and developed as a wedding present vehicle for Ali MacGraw (formerly Diana Vreeland’s assistant at Harper’s Bazaar magazine) from her then-husband Robert Evans. The project was derailed from its initial purpose when MacGraw fell in love with her The Getaway (Sam Peckinpah, 1972) co-star Steve McQueen and divorced Evans.

Evans in his home Woodland, built by architect John Woolf

Evans in his home Woodland, built by architect John Woolf

The producer with Tatjiana Shoan. Harper’s Bazaar, 2004

The producer with Tatjiana Shoan. Harper’s Bazaar, 2004

Steve McQueen and Ali MacGraw

Steve McQueen and Ali MacGraw

Stills from The Great Gatsby (Jack Clayton, 1974)

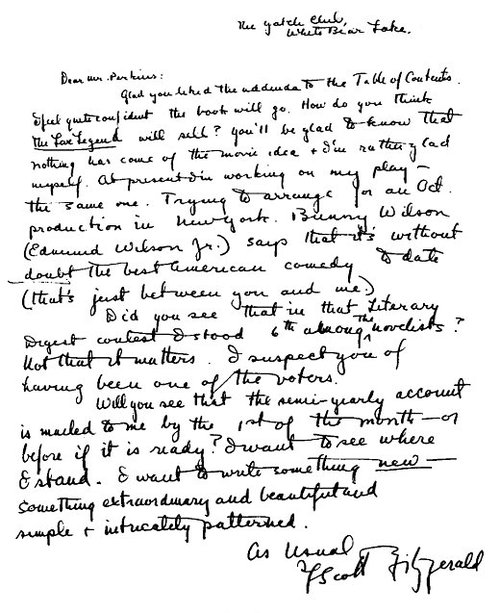

Automobiles are almost treated as a character in the plot of Fitzgerald’s book. Myrtle Wilson was knocked down by a car and this sad event unchains the climax of the story. Plus, Fitzgerald to his editor Maxwell Perkins that the name of Jordan Baker (a character based on the golfer Edith Cumming) is a combination between the two then-popular automobile brands, the Jordan Motor Car Company and the Baker Motor Vehicle, as an allusion to Jordan’s “fast” reputation and the freedom now presented to Americans, especially women of 1920s.

Ralph Lauren

Ralph Lauren

Ralph Lauren who (as we know) made the costumes for Jack Clayton’s The Great Gastby, has a penchant for cars. His collection of classic automobiles is another dimension of his own persona. An amazing lineup of 50-plus dream machines that have all been restored to glory, the convoy is a portal to the past, when men like Brokaw drove their race cars home from the track at the end of the day and manufacters were the manifestations of their designers: Jean Bugatti, Enzo Ferrari, Ferdinand Porsche… RL’s gateway drug was a white ’61 Morgan convertible with red leather seats, which he bought in 1963- back when he was a travelling salesman for the Boston-based tie company A. Rivetz & Co.- and was later forced to sell when he couldn’t afford a garage in Manhattan.

Steve McQueen

Steve McQueen

And it’s a little bit curious and probably not coincidental that one of Ralph Lauren’s cottages is adorned with black-and-white photos of Greta Garbo, Johnny Depp and Steve McQueen, a man who also loved engines and made himself just like Jay Gatsby and Lauren did.