Orpheus Emerged is a novella written by Jack Kerouac in 1945 when he was at Columbia University and was just 23 years old. It was discovered after his death but not released until 2000 (by his estate).

It chronicles the passions, conflicts, and dreams of a group of bohemians searching for truth while studying at a university. Kerouac wrote the story shortly after meeting Allen Ginsberg, William S. Burroughs, Lucien Carr, and others in and around Columbia University who would form the core of the Beats.

The journal Kerouac referred to as “The Plan For The Novel Galloway,” provides deep insights into Jack’s growing organizational skills. The Galloway notes contain 22 sections which break down potential scenes for the novel, plus there are revelations about Jack’s characters (himself, his family, friends, etc.) and how they would be developed. Although, eventually Kerouac would not choose to include many of these scenes in The Town and The City, he would later utilize some of them in Maggie Cassidy and Vanity of Duluoz. Jack was driving towards a literary feeling, something uniquely his own that could answer his artistic callings. In section 19, Jack wrote: “Whereas, in most novels, the climax of the narrative is dramatic, this, not being so much a narrative as a fugue of moods, must be a musical climax – the climax in Galloway must be referred to as such: – it is not the dramatic outbreak of a narrative’s laborious building up, but sheer triumph erupting like a mood without cause over the mass of life – moods strung and woven thereunto. The same method I applied in Orpheus Emerged, where realism was established in order to vent full and glowing truth of a mystico-spiritual experience…although that work, in itself, was of the poorest quality, really.”

So Kerouac originally planned to write his first novel in an improved but similar style to the experimental short novel Orpheus Emerged. It resembles the work of Camus and Sartre far more than the edited, published version of The Town and The City. Journals from 1943 and 1944 reveal Kerouac’s outline and intended symbolism in Orpheus Emerged and are interesting when compared to Galloway. The charts of symbols are much the same, and the stated themes of both intend to deal with the search of a “young American Artist.” The artist’s search centered around the choice to live life for art or to live it for life itself. Orpheus Emerged pursued this theme through its main character, Michael, who was described as “the genius of imagination and art.” He was a mysterious sufferer who followed his artistic “calling,” yet strangely only shared his poetry and money with a possible twin, Paul, “the genius of life and love.” Both men are 22, they are linked to Marcel Orpheus (also 22) in ways only understandable by the appearance of “Helen,” the beloved of Marcel Orpheus.”

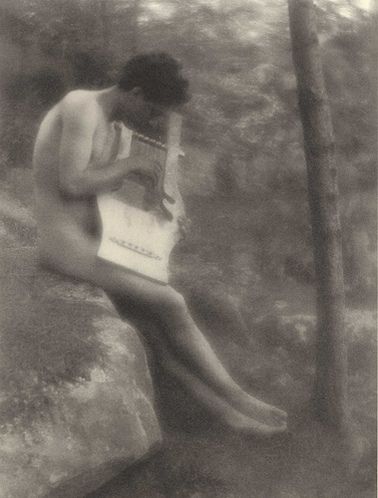

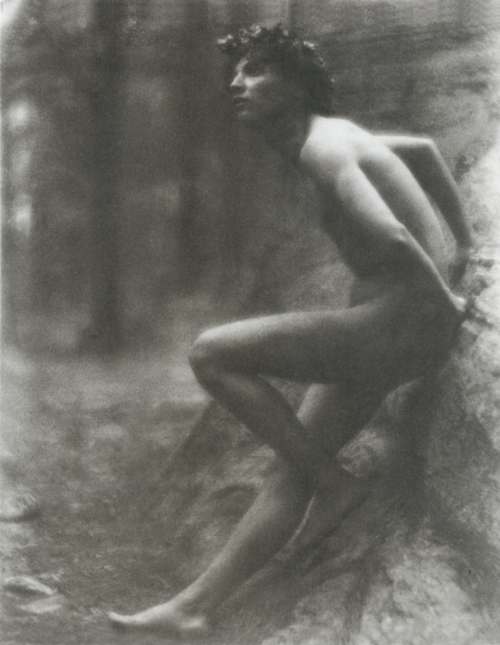

Orpheus, of course, from Greek legend was the gifted poet and musician who after receiving a lyre from Apollo became supernatural is his artistic abilities. Helen, the daughter of Zeus represented the magnificence and joy that beauty can bestow, yet with it came the promise of doom. With the glow of these mythological characters as a back drop, Michael’s story evolved; he was attempting to transcend man’s mortal emotions, and through art achieve immortality. The other characters in Orpheus Emerged, Leo (a bright student possibly based on Ginsberg), Arthur (a student who writes possibly Lucien Carr), Anthony, a struggling alcoholic, and the women who are manipulated by these men, are all mystified by the oddness of Michael’s emotional state. It is only Paul who appeared to have some understanding of and connection to Michael. At an innocuous party, Paul revealed to Michael that: …”She’s (Helen) coming here soon,” which launched Michael into an unexplainable, violent attack on Paul.

This behavior and a subsequent doomed affair between Michael and Marie (Anthony’s wife) began a downward spiral and unraveling of Michael’s personality. In a drunken rage, he rebuked Leo’s attempts to console him while the two men drank in a neighborhood bar. Later, Michael wandered the rainy city streets until, so distraught, he contemplated ending his life by plunging into the cold depths of the river. But Michael decided to postpone his suicidal act because he desired to once more see Paul, and “hurl curses in his face.” Michael found Paul in his room, but also discovered that Helen had, indeed, returned, and in her presence he descended into a complete nervous breakdown. Strangely, he announced to Paul that both of their lives were about to end, and to Helen, he declared that he was not worthy of her for, like other ordinary human beings, he had settled for merely living his life.

The baffling scene ends with Helen holding both men’s hands, and the notion of Michael and Paul being one and the same person, though unstated, was implied. Like the “fugue of moods” Kerouac had promised, the story mysteriously ended with Leo, Arthur, and another student arguing. The men had observed Helen riding off in a trolley car with either Michael of Paul, there is not agreement over which one it was. Finally, Arthur, we are told, reached some understanding of this bizarre episode after finding a note in his mailbox which made reference to and was signed “Orpheus.”

As an unfinished work of fiction, Orpheus Emerged is a strange and tantalizing story that suffers from numerous structural flaws. The lack of clarity, intentional or not, diminishes the novels seriousness, the setting is poorly focused, and the dialog is barely believable. The overall effect is one of sheer bewilderment. Yet, viewed as a journal entry one can better understand that “Orpheus” was more of a thematic experiment, and that Kerouac recognized it to be a stylistic failure. It’s influence on the Galloway journals is also purely thematic. Kerouac’s own artistic journey and his struggles with choosing between the artist’s life and the life he knew from his family and the town of Lowell, undeniably are the source of inspiration. But, Kerouac realized he needed to broaden his scope and therefore wrote The Town and The City in a classically structured style where “the climax of the narrative is dramatic.” He had come full circle from his intentions of style in Orpheus Emerged.

Later in life, Kerouac, no doubt, must have found it annoying when he was said to have been an undisciplined writer. Jack took the brunt of that criticism knowing full well how hard he had worked, in a “disciplined” sense, to evolve into a writer who could write brilliantly from multiple styles: as an objective narrator, a first person confessionalist, an expressive poet, a creator of mythical characters, and a chronicler of history. Kerouac’s journals are the unarguable evidence of the dues he paid.

Minotauromachy, Pablo Picasso, 1935

Minotauromachy, Pablo Picasso, 1935