“A hero is someone who understands the responsibility that comes with his freedom.”

Bob Dylan

Baptism: A Journey Through Our Time was a 1968 album of poetry spoken and sung by Joan Baez.

Baptism: A Journey Through Our Time was a 1968 album of poetry spoken and sung by Joan Baez.

Artwork by Robert Peak. Design by Jules Halfant

TRACK LISTING

Old Welsh Song” (Henry Treece)

2.”I Saw the Vision of Armies” (Walt Whitman)

3.”Minister of War” (Arthur Waley)

4.”Song In the Blood” (Lawrence Ferlinghetti/Jacques Prévert)

5.”Casida of the Lament” (J.L. Gili/Federico García Lorca)

6.”Of the Dark Past” (James Joyce)

7.”London” (William Blake)

8.”In Guernica” (Norman Rosten)

9.”Who Murdered the Minutes” (Henry Treece)

10.”Oh, Little Child” (Henry Treece)

11.”No Man Is an Island” (John Donne)

12.”Portrait of the Artist As a Young Man” (James Joyce)

13.”All the Pretty Little Horses” (traditional)

14.”Childhood III” (Arthur Rimbaud/Louis Varese)

15.”The Magic Wood” (Henry Treece)

16.”Poems from the Japanese” (Kenneth Rexroth)

17.”Colours” (P. Levi, R. Milner-Gulland, Yevgeny Yevtushenko)

18.”All in green went my love riding” (E. E. Cummings)

19.”Gacela of the Dark Death” (Federico García Lorca/Stephen Spender)

20.”The Parable of the Old Man and the Young” (Wilfred Owen)

21.”Evil” (N. Cameron/Arthur Rimbaud)

22.”Epitaph for a Poet” (Countee Cullen)

23.”Mystic Numbers- 36″

24.”When The Shy Star Goes Forth In Heaven” (James Joyce)

25.”The Angel” (William Blake)

26.”Old Welsh Song” (Henry Treece)

Joan Baez‘s most unusual album, Baptism is of a piece with the “concept” albums of the late ’60s, but more ambitious than most and different from all of them. Baez by this time was immersed in various causes, concerning the Vietnam War, the human condition, and the general state of the world, and it seemed as though every note of music that she sang was treated as important — sometimes in a negative way by her opponents; additionally, popular music was changing rapidly, and even rock groups that had seldom worried in their music about too much beyond the singer’s next sexual conquest were getting serious. Baptism was Baez getting more serious than she already was, right down to the settings of her music, and redirecting her talent from folk song to art song, complete with orchestral accompaniment. Naturally, her idea of a concept album would differ from that of, say, Frank Sinatra or The Beatles. Baptism was a body of poetry selected, edited, and read and sung by Baez, and set to music by Peter Schickele (better known for his comical musical “discoveries” associated with “P.D.Q. Bach,” but also a serious musician and composer). In 1968, amid the strife spreading across the world, the album had a built-in urgency that made it work as a mixture of art and message — today, it seems like a precious and overly self-absorbed period piece.

A clip of Whitman’s poem spoken by Joan Baez can be listened on The Genealogy of Style‘s Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/pages/The-Genealogy-of-Style/597542157001228

Natalie Merchant was born October 26, 1963, in Jamestown, New York, the third of four children of Anthony and Ann Merchant. Her paternal grandfather, who played the accordion, mandolin and guitar, emigrated to the United States from Sicily; his surname was “Mercante” before it was Anglicized.

When Merchant was a child, her mother listened to music (primarily Petula Clark but also The Beatles, Al Green, Aretha Franklin) and encouraged her children to study music, but she wouldn’t allow TV after Natalie was 12. “I was taken to the symphony a lot because my mother loved classical music. But I was dragged to see Styx when I was 12. We had to drive 100 miles to Buffalo, New York. Someone threw up next to me and people were smoking pot. It was terrifying. I remember Styx had a white piano which rose out of the stage. It was awe-inspiring and inspirational.” “She [her mother] had show tunes, she had the soundtrack from West Side Story (Robert Wise, 1961) and South Pacific (Joshua Logan, 1958). And then eventually… she’d always liked classical music and then she married a jazz musician, so that’s the kind of music I was into. I never really had friends who sat around and listened to the stereo and said ‘hey, listen to this one’, so I’d never even heard of who Bob Dylan was until I was 18.”

John Lennon received a letter from a pupil at Quarry Bank High School, which he had attended. The writer mentioned that the English master was making his class analyse The Beatles‘ lyrics (Lennon wrote an answer, dated 1 September 1967, which was auctioned by Christie’s of London in 1992). Lennon, amused that a teacher was putting so much effort into understanding the Beatles’ lyrics, decided to write in his next song the most confusing lyrics that he could.

The genesis of the lyrics is found in three song ideas that Lennon was working on, the first of which was inspired by hearing a police siren at his home in Weybridge; Lennon wrote the lines “Mis-ter cit-y police-man” to the rhythm and melody of the siren. The second idea was a short rhyme about Lennon sitting in his garden, while the third was a nonsense lyric about sitting on a corn flake. Unable to finish the ideas as three different songs, he eventually combined them into one. The lyrics also included the phrase “Lucy in the sky” from Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds from Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band earlier in the year.

The Walrus and The Carpenter as illustrated by John Tenniel

The Walrus and The Carpenter as illustrated by John Tenniel

The walrus is a reference to the walrus in Lewis Carroll‘s poem The Walrus and the Carpenter (from the book Through the Looking-Glass). Lennon later expressed dismay upon belatedly realising that the walrus was a villain in the poem.

The final catalyst of the song occurred when Lennon’s friend and former fellow member of the Quarrymen, Peter Shotton, visited and Lennon asked Shotton about a playground nursery rhyme they sang as children. Shotton remembered:

“Yellow matter custard, green slop pie, All mixed together with a dead dog’s eye, Slap it on a butty, ten foot thick, Then wash it all down with a cup of cold sick.”

Lennon borrowed a couple of words, added the three unfinished ideas and the result was I Am the Walrus. The Beatles’ official biographer Hunter Davies was present while the song was being written and wrote an account in his 1968 biography of the Beatles. Lennon remarked to Shotton, “Let the fuckers work that one out.” Shotton was also responsible for suggesting to Lennon to change the lyric “waiting for the man to come” to “waiting for the van to come”.

The Beatles in costume filming Magical Mystery Tour

The Beatles in costume filming Magical Mystery Tour

Lennon claimed he wrote the first two lines on separate acid trips; he explained much of the song to Playboy in 1980:

“The first line was written on one acid trip one weekend. The second line was written on the next acid trip the next weekend, and it was filled in after I met Yoko… I’d seen Allen Ginsberg and some other people who liked Dylan and Jesus going on about Hare Krishna. It was Ginsberg, in particular, I was referring to. The words ‘Element’ry penguin’ meant that it’s naïve to just go around chanting Hare Krishna or putting all your faith in one idol. In those days I was writing obscurely, à la Dylan.”

“It never dawned on me that Lewis Carroll was commenting on the capitalist system. I never went into that bit about what he really meant, like people are doing with the Beatles’ work. Later, I went back and looked at it and realized that the walrus was the bad guy in the story and the carpenter was the good guy. I thought, Oh, shit, I picked the wrong guy. I should have said, ‘I am the carpenter.’ But that wouldn’t have been the same, would it? [Sings, laughing] ‘I am the carpenter….'”

Seen in the Magical Mystery Tour film singing the song, Lennon, apparently, is the walrus; on the track-list of the accompanying soundtrack EP/LP however, underneath I Am the Walrus are printed the words ‘ “No you’re not!” said Little Nicola’ (in the film, Nicola is a little girl who keeps contradicting everything the other characters say). Lennon returned to the subject in the lyrics of three of his subsequent songs: in the 1968 Beatles song Glass Onion he sings, “I told you ’bout the walrus and me, man/You know that we’re as close as can be, man/Well here’s another clue for you all/The walrus was Paul”; in the third verse of Come Together he sings the line “he bag production, he got walrus gumboot”; and in his 1970 solo song God, admits “I was the walrus, but now I’m John.”

To watch the clip from Magical Mystery Tour, please take a gander at The Genealogy of the Style‘s Facebook page: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7r52ZBx0KMI

The gatepost to Strawberry Field, which is now a popular tourist attraction in Liverpool

The gatepost to Strawberry Field, which is now a popular tourist attraction in Liverpool

Strawberry Fields Forever was written by John Lennon and credited to the Lennon–McCartney songwriting partnership. It was inspired by Lennon’s memories of playing in the garden of Strawberry Field, a Salvation Army children’s home near where he grew up in Liverpool.

The song was the first track recorded during the sessions for The Beatles‘ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967), and was intended for inclusion on the album. Instead, with the group under record-company pressure to release a single, it was issued in February 1967 as a double A-side with Penny Lane.

John Lennon’s Strawberry Fields Forever and Paul McCartney‘s Penny Lane shared the theme of nostalgia for their early years in Liverpool. Although both referred to actual locations, the two songs also had strong surrealistic and psychedelic overtones. Producer George Martin said that when he first heard Strawberry Fields Forever, he thought it conjured up a “hazy, impressionistic dreamworld”.

Lennon began writing the song in Almería, Spain, during the filming of Richard Lester‘s How I Won the War in September–October 1966. The earliest demo of the song, recorded in Almería, had no refrain and only one verse: “There’s no one on my wavelength / I mean, it’s either too high or too low / That is you can’t you know tune in but it’s all right / I mean it’s not too bad”. He revised the words to this verse to make them more obscure, then wrote the melody and part of the lyrics to the refrain (which then functioned as a bridge and did not yet include a reference to Strawberry Fields). He then added another verse and the mention of Strawberry Fields. The first verse on the released version was the last to be written, close to the time of the song’s recording. For the refrain, Lennon was again inspired by his childhood memories: the words “nothing to get hung about” were inspired by Aunt Mimi’s strict order not to play in the grounds of Strawberry Field, to which Lennon replied, “They can’t hang you for it.” The first verse Lennon wrote became the second in the released version, and the second verse Lennon wrote became the last in the release.

The promotional film for Strawberry Fields Forever was an early example of what later became known as a music video. It was filmed on 30 and 31 January 1967 at Knole Park in Sevenoaks, Kent. The clip was directed by Peter Goldmann, a Swedish television director who had been recommended to the Beatles by their mutual friend Klaus Voormann. The film featured reverse film effects, stop motion animation, jump-cuts from daytime to night-time, and the Beatles playing and later pouring paint over the upright piano.

You can watch the promotional film on The Genealogy of Style‘s Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/pages/The-Genealogy-of-Style/597542157001228?ref=hl

Still from Across the Universe (Julie Taymor, 2007)

Still from Across the Universe (Julie Taymor, 2007)

“There were never strawberries

like the ones we had

that sultry afternoon

sitting on the step

of the open french window

facing each other

your knees held in mine

the blue plates in our laps

the strawberries glistening

in the hot sunlight

we dipped them in sugar

looking at each other

not hurrying the feast

for one to come

the empty plates

laid on the stone together

with the two forks crossed

and I bent towards you

sweet in that air

in my arms

abandoned like a child

from your eager mouth

the taste of strawberries

in my memory

lean back again

let me love you

let the sun beat

on our forgetfulness

one hour of all

the heat intense

and summer lightning

on the Kilpatrick hills

let the storm wash the plates”

Edwin Morgan

The Holy Mountain (Alejandro Jodorowsky, 1973) movie poster

René Magritte‘s The Son of Man appears in Alejandro Jodorowsky’s film The Holy Mountain, on a wall in the house of Jupiter. The film was produced by Beatles manager Allen Klein of ABKCO Music and Records, after Jodorowsky scored an underground phenomenon with El Topo (The Mole) and the acclaim of both John Lennon and George Harrison (Lennon and Yoko Ono put up production money).

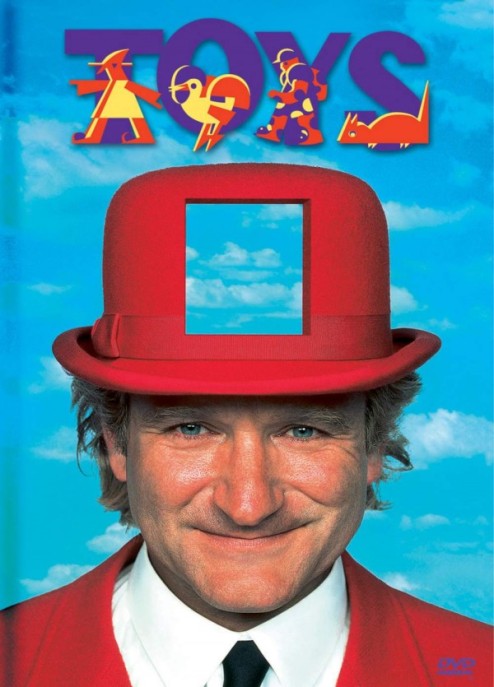

Robin Williams in Toys (Barry Levinson, 1992).

Robin Williams in Toys (Barry Levinson, 1992).

The set design, costumes, and promotional poster reflect the painting’s style.

A parody of the painting, with Bart behind the floating apple, can be seen briefly at the start of The Simpsons episode No. 86 Treehouse of Horror IV (1993)

A parody of the painting, with Bart behind the floating apple, can be seen briefly at the start of The Simpsons episode No. 86 Treehouse of Horror IV (1993)

The painting appears briefly on the video for Michael Jackson and Janet Jackson’s song Scream , on the “Gallery” section:

Still from Michael Jackson and Janet Jackson’s Scream music video (Mark Romanek, 1995)

Still from Michael Jackson and Janet Jackson’s Scream music video (Mark Romanek, 1995)

The Thomas Crown Affair (John McTiernan, 1999)

The Thomas Crown Affair (John McTiernan, 1999)

The Son of Man appears several times in the 1999 version of The Thomas Crown Affair, especially in the final robbery scenes when men wearing bowler hats and trench coats carry briefcases throughout the museum to cover Crown’s movements and confuse the security team.

Stranger Than Fiction (Marc Forster, 2006)

Stranger Than Fiction (Marc Forster, 2006)

This is not an Apple, illustration by John Cox, 2007

This is not an Apple, illustration by John Cox, 2007

In the film Mr Magorium’s Wonder Emporium (Zach Helm, 2007), the painting is seen hanging on the wall half finished; at the end of the film Mr Magorium is seen to be painting the rest of it.

This painting also shows up at the end of the film Bronson (Nicolas Winding Refn, 2008). British prisoner Charlie Bronson takes a hostage and turns him into this particular portrait

In the movie 500 Days of Summer (Marc Webb, 2009), the bowler hat and green apple can be seen in Summer’s apartment

The cover of the book Rubies in the Orchard: How to Uncover the Hidden Gems in Your Business (2009) has a version of the painting, with a pomegranate

The cover of the book Rubies in the Orchard: How to Uncover the Hidden Gems in Your Business (2009) has a version of the painting, with a pomegranate

In Jimmy Liao’s illustrated book Starry Starry Night (2011), the protagonist girl, with the painting illustrated behind her, imitates the painting to express her protest against her parents’ long term fighting.

In Jimmy Liao’s illustrated book Starry Starry Night (2011), the protagonist girl, with the painting illustrated behind her, imitates the painting to express her protest against her parents’ long term fighting.

In Gary Braunbeck’s novel Keepers (2005), the antagonist figures (the “Keepers” of the title) resemble the nattily-dressed, bowler-hatted figures of Magritte’s painting. Also, in the opening scene of the book, the reference is directly made and explained to this resemblance because of an apple-scented car air freshener printed with the image of the painting hanging in the protagonist’s car.

In Lev Grossman’s 2009 novel The Magicians the antagonist is a man wearing a suit, with his face obscured by a leafed branch suspended in midair.

The Beatles‘ accountants had informed the group that they had two million pounds which they could either invest in a business venture or else lose to the Inland Revenue, because corporate/business taxes were lower than their individual tax bills. According to Peter Brown, personal assistant to Beatles’ manager Brian Epstein, activities to find tax shelters for the income that the Beatles generated began as early as 1963–64, when Dr Walter Strach was put in charge of such operations. First steps into that direction were the foundation of Beatles Ltd and, in early 1967, Beatles and Co.

The Beatles’ publicist, Derek Taylor, remembered that Paul McCartney had the name for the new company when he visited Taylor’s company flat in London: “We’re starting a brand new form of business. So, what is the first thing that a child is taught when he begins to grow up? A is for Apple”. McCartney then suggested the addition of Apple Core, but they could not register the name, so they used “Corps” (having the same pronunciation).

The Belgian Beatles Society page says that in an interview with Johan Ral in 1993, Paul McCartney recalled:

“….I had this friend called Robert Fraser, who was a gallery owner in London. We used to hang out a lot. And I told him I really loved Magritte. We were discovering Magritte in the sixties, just through magazines and things. And we just loved his sense of humour. And when we heard that he was a very ordinary bloke who used to paint from nine to one o’clock, and with his bowler hat, it became even more intriguing. Robert used to look around for pictures for me, because he knew I liked him. It was so cheap then, it’s terrible to think how cheap they were. But anyway, we just loved him … One day he brought this painting to my house. We were out in the garden, it was a summer’s day. And he didn’t want to disturb us, I think we were filming or something. So he left this picture of Magritte. It was an apple – and he just left it on the dining room table and he went. It just had written across it “Au revoir”, on this beautiful green apple. And I thought that was like a great thing to do. He knew I’d love it and he knew I’d want it and I’d pay him later. […] So it was like wow! What a great conceptual thing to do, you know. And this big green apple, which I still have now, became the inspiration for the logo. And then we decided to cut it in half for the B-side!”

Le Jeu de la Mourre, René Magritte, 1966

Le Jeu de la Mourre, René Magritte, 1966

Taking Magritte for inspiration, the Apple record labels were designed by a fellow named Gene Mahon, an advertising agency designer. The Beatles Collection website has a great summary of how this all came about:

“[It was Gene Mahon who] proposed having different labels on each side of the record. One side would feature a full apple that would serve as a pure symbol on its own without any text. All label copy would be printed on the other side’s label, which would be the image of a sliced apple. The white-colored inside surface of the sliced apple provided a good background for printing information.

The idea of having no print on the full apple side was abandoned when EMI advised Apple that the contents of the record should appear on both sides of the disc for copyright and publishing reasons. Although Mahon’s concept was rejected for legal (and perhaps marketing) reasons, his idea of using different images for each side of the record remained. Mahon hired Paul Castell to shoot pictures of green, red and yellow apples, both full and sliced. The proofs were reviewed by the Beatles and Neil Aspinall, with the group selecting a big green Granny Smith apple to serve as the company’s logo. A sliced green apple was picked for B side. Alan Aldridge provided the green script perimeter print for labels [on UK, EU and Australian releases – this does not appear on US labels] and, in all likelihood, the script designation on the custom record sleeve.”

“He was searching for something much higher, much deeper. It does seem like he already had some Indian background in him. Otherwise, it’s hard to explain how he got so attracted to a particular type of life and philosophy, even religion. It seems very strange, really. Unless you believe in reincarnation.”

Ravi Shankar

Ravi Shankar and George Harrison

Ravi Shankar and George Harrison

By the mid-1960s George Harrison had become an admirer of Indian culture and mysticism, introducing it to the other Beatles. During the filming of Help! (Richard Lester, 1965) in the Bahamas, they met the founder of Sivananda Yoga, Vishnudevananda Saraswati, who gave each of them a signed copy of his book, The Complete Illustrated Book of Yoga. Between the end of the last Beatles tour in 1966 and the beginning of the Sgt Pepper recording sessions, he made a pilgrimage to Bombay with his wife Pattie Boyd, where he studied sitar, met several gurus, and visited various holy places. In 1968 he travelled to Rishikesh in northern India with the other Beatles to study meditation with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. Harrison’s use of psychedelic drugs encouraged his path to meditation and Hinduism. He commented: “For me, it was like a flash. The first time I had acid, it just opened up something in my head that was inside of me, and I realized a lot of things. I didn’t learn them because I already knew them, but that happened to be the key that opened the door to reveal them. From the moment I had that, I wanted to have it all the time – these thoughts about the yogis and the Himalayas, and Ravi’s music.”

By 1965’s Rubber Soul, Harrison had begun to lead the other Beatles into folk rock through his interest in The Byrds and Bob Dylan, and towards Indian classical music through his use of the sitar on Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown). He later called Rubber Soul his “favourite [Beatles] album”. Revolver (1966) included three of his compositions: Taxman, Love You To and I Want to Tell You. His introduction of the drone-like tambura part on Lennon’s Tomorrow Never Knows exemplified the band’s ongoing exploration of non-Western instruments. The tabla-driven Love You To was the Beatles’ first genuine foray into Indian music. According to the ethnomusicologist David Reck, the song set a precedent in popular music as an example of Asian culture being represented by Westerners respectfully and without parody. Harrison continued to develop his interest in non-Western instrumentation, playing swarmandal on Strawberry Fields Forever.

During the Beatles’ American tour in August 1965, Harrison’s friend David Crosby of The Byrds introduced him to Indian classical music and the work of sitar maestro Ravi Shankar. Harrison described Shankar as “the first person who ever impressed me in my life … and he was the only person who didn’t try to impress me.” Harrison became fascinated with the sitar and immersed himself in Indian music. According to Peter Lavezzoli, Harrison’s introduction of the instrument on the Beatles’ song “Norwegian Wood” “opened the floodgates for Indian instrumentation in rock music, triggering what Shankar would call ‘The Great Sitar Explosion’ of 1966–67”. Lavezzoli described Harrison as “the man most responsible for this phenomenon”.

“I’m living in the material world

Living in the material world

can’t say what I’m doing here

But I hope to see much clearer,

After living in the material world

I got born into the material world

Getting worn out in the material world

Use my body like a car,

Taking me both near and far

Met my friends all in the material world

Met them all there in the material world

John and Paul here in the material world

Though we started out quite poor

We got ‘Richie’ on a tour

Got caught up in the material world

From the Spiritual Sky,

Such sweet memories have I

To the Spiritual Sky

How I pray

Yes I pray

That I won’t get lost

Or go astray

As I’m fated for the material world

Get frustrated in the material world

Senses never gratified

Only swelling like a tide

That could drown me in the

Material world

From the Spiritual Sky,

Such sweet memories have I

To the Spiritual Sky

How I pray

Yes I pray

That I won’t get lost

Or go astray

While I’m living in the material world

Not much ‘giving’ in the material world

Got a lot of work to do

Try to get a message through

And get back out of this material world

I’m living in the material world

Living in the material world

I hope to get out of this place

By the LORD SRI KRSNA’S GRACE

My salvation from the material world

Big Ending”

George Harrison

1973

Photograph of George Harrison chosen for the publicity posters (and for the front cover of the accompanying book) of Living In The Material World. it was taken during the filming for the Beatles movie Help! (Richard Lester, 1965).

Photograph of George Harrison chosen for the publicity posters (and for the front cover of the accompanying book) of Living In The Material World. it was taken during the filming for the Beatles movie Help! (Richard Lester, 1965).

In 2007 Martin Scorsese wrote a short cinematographic appreciation of Help! for the book that comes with both the standard and the deluxe DVD box set re-issue of the mentioned film .

George Harrison: Living in the Material World (Martin Scorsese, 2011) is a documentary film based on the life of Beatles member George Harrison. It earned six nominations at the 64th Primetime Emmy Awards, winning two Emmy Awards for Outstanding Nonfiction Special and Outstanding Directing for Nonfiction Programming.

George Harrison: Living in the Material World (Martin Scorsese, 2011) is a documentary film based on the life of Beatles member George Harrison. It earned six nominations at the 64th Primetime Emmy Awards, winning two Emmy Awards for Outstanding Nonfiction Special and Outstanding Directing for Nonfiction Programming.

The film follows music legend George Harrison’s story from his early life in Liverpool, the Beatlemania phenomenon, his travels to India, the influence of Indian culture in his music, and his relevance and importance as a member of The Beatles. It consists of previously unseen footage and interviews with Olivia and Dhani Harrison, friends, and many others.

After Harrison’s death in 2001, various production companies approached his widow Olivia about producing a film about her late husband’s life. She declined because he had wanted to tell his own life story through his video archive. Upon meeting Scorsese, she gave her blessings and signed on to the film project as a producer.

According to Scorsese, he was attracted to the project because “That subject matter has never left me…The more you’re in the material world, the more there is a tendency for a search for serenity and a need to not be distracted by physical elements that are around you. His music is very important to me, so I was interested in the journey that he took as an artist. The film is an exploration. We don’t know. We’re just feeling our way through.”

Throughout 2008 and 2009, Scorsese alternated working between Shutter Island and the documentary.

To watch the trailer, please, take a gander at The Genealogy of Style‘s Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/pages/The-Genealogy-of-Style/597542157001228?ref=hl

“..Pools of sorrow waves of joy

Are drifting through my opened mind

Possessing and caressing me

Jai Guru Deva, om

Nothing’s gonna change my world

Nothing’s gonna change my world

Nothing’s gonna change my world

Nothing’s gonna change my world…”

Across the Universe

John Lennon & Paul McCartney

The Beatles on the set of Help! (Richard Lester, 1965) at the Nassau Beach Hotel, Bahamas

The Beatles on the set of Help! (Richard Lester, 1965) at the Nassau Beach Hotel, Bahamas

Page of the Help! script. In the film there’s a very brief scene where the Beatles, after being chased by the bad guys, end up in the swimming pool of a resort hotel with all the guests looking on as they emerge wet, bedraggled and fully-clothed from the pool.

Page of the Help! script. In the film there’s a very brief scene where the Beatles, after being chased by the bad guys, end up in the swimming pool of a resort hotel with all the guests looking on as they emerge wet, bedraggled and fully-clothed from the pool.

While My Guitar Gently Weeps is a song written by George Harrison, first recorded by The Beatles in 1968 for their eponymous double album (also known as The White Album). The song features a lead guitar solo by Eric Clapton, although he was not formally credited on the album. While My Guitar Gently Weeps is ranked at number 136 on Rolling Stone ‘s “The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time”, number 7 on the magazine’s list of the 100 Greatest Guitar Songs of All Time, and number 10 on its list of The Beatles 100 Greatest Songs.

Inspiration for the song came to Harrison when reading the I Ching, which, as Harrison put it, “seemed to me to be based on the Eastern concept that everything is relative to everything else… opposed to the Western view that things are merely coincidental.” Taking this idea of relativism to his parents’ home in northern England, Harrison committed to write a song based on the first words he saw upon opening a random book. Those words were “gently weeps”, and he immediately began writing the song. As he said:

“I wrote While My Guitar Gently Weeps at my mother’s house in Warrington. I was thinking about the Chinese I Ching, the Book of Changes… The Eastern concept is that whatever happens is all meant to be, and that there’s no such thing as coincidence — every little item that’s going down has a purpose.

While My Guitar Gently Weeps was a simple study based on that theory. I decided to write a song based on the first thing I saw upon opening any book — as it would be relative to that moment, at that time. I picked up a book at random, opened it, saw ‘gently weeps’, then laid the book down again and started the song.”

The I Ching has had a lasting influence on both East and West. In the West, it attracted the attention of intellectuals as early as the days of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, and in English translation, it had notable impact on 1960s counterculture figures such as Philip K. Dick, Allen Ginsberg, Bob Dylan, John Cage, Jorge Luis Borges, I.M. Pei and Herman Hesse. Carl Jung wrote of the book, “Even to the most biased eye, it is obvious that this book represents one long admonition to careful scrutiny of one’s own character, attitude, and motives.”

To watch a clip of this song, please take a gander at The Genealogy of Style‘s Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/pages/The-Genealogy-of-Style/597542157001228

VIEWING THE DISTANT

1. “Without passing out of the gate

The world’s course I prognosticate.

Without peeping through the window

The heavenly Reason I contemplate.

The further one goes,

The less one knows.”

2. Therefore the holy man does not travel, and yet he has knowledge. He does not see things, and yet he defines them. He does not labor, and yet he completes.

Tao Te Ching (Chapter 47)

Attributed to Laozi

The Inner Light is a song written by George Harrison that was first released by The Beatles as a B-side to Lady Madonna. It was the first Harrison composition to be featured on a Beatles single. The lyrics are a rendering of the 47th chapter (sometimes titled Viewing the Distant in translations) of the Taoist Tao Te Ching. An instrumental alternate take was released in 2014 on George Harrison’s Wonderwall Music remastered CD as a bonus track.

In his autobiography I, Me, Mine, Harrison writes that the song was inspired by a letter from Juan Mascaró, a Sanskrit scholar at Cambridge University, who sent him a copy of his book Lamps of Fire (a wide-ranging anthology of religious writings, including some from the Tao Te Ching) and asked him: “… might it not be interesting to put into your music a few words of Tao, for example number 48, page 66 of the book.” Harrison states: “In the original poem, the verse says ‘Without going out of my door, I can know the ways of heaven.’ And so to prevent any misinterpretations — and also to make the song a bit longer — I did repeat that as a second verse but made it: “Without going out of your door / You can know all things on earth / Without looking out of your window / You can know the ways of heaven” — so that it included everybody”. The passage Harrison refers to, however, corresponds to what English translations normally number as “47”, rather than “48”. D. C. Lau’s translation of the Tao Te Ching 47, for example, states: “Without stirring abroad / One can know the whole world / Without looking out of the window / One can see the way of heaven.”

Isn’t It a Pity is a song by English musician George Harrison from his 1970 solo album All Things Must Pass. It appears in two variations there: one the well-known, seven-minute version; the other a reprise, titled Isn’t It a Pity (Version Two). Harrison wrote the song in 1966, but it was rejected for inclusion on releases by The Beatles. In many countries around the world, the song was also issued on a double A-side single with My Sweet Lord.

An anthemic ballad and one of Harrison’s most celebrated compositions, Isn’t It a Pity has been described as the emotional and musical centrepiece of All Things Must Pass and “a poignant reflection on The Beatles’ coarse ending”. Co-produced by Phil Spector, the recording employs multiple keyboard players, rhythm guitarists and percussionists, as well as orchestration by arranger John Barham. In its extended fadeout, the song references the closing refrain of the Beatles’ 1968 hit Hey Jude. Other musicians on the recording include Ringo Starr, Billy Preston, Gary Wright and the band Badfinger, while the reprise version features Eric Clapton on lead guitar.

While no longer the “really tight” social unit they had been throughout the chaos of Beatlemania – or the “four-headed monster”, as Mick Jagger famously called them – the individual Beatles were still bonded by genuine friendship during their final, troubled years as a band, even if it was now more of a case of being locked together at a deep psychological level after such a sustained period of heightened experience. Eric Clapton has described this bond as being just like that of a typical family, “with all the difficulties that entails”. When the band finally split, in April 1970 – a “terrible surprise” for the outside world, in the words of author Mark Hertsgaard, “like the sudden death of a beloved young uncle” – even the traditionally most disillusioned Beatle, George Harrison, suffered a mild bereavement.

“Well I remember that wall, that brick … Bob Gill and I never quite recovered our compatibility but the brick did have to go. Were we right? Yes.”

Derek Taylor

(recalling difficulties with artist Bob Gill over Harrison’s requested alteration to his cover design)

Wonderwall Music is the soundtrack album to the film Wonderwall (Joe Massot, 1968), and the debut solo release by English musician George Harrison. It was the first album to be issued on The Beatles‘ Apple record label, and the first solo album by a member of that band. The songs are all instrumental pieces, except for occasional non-English vocals, and a slowed-down spoken word segment on the track Dream Scene. Harrison recorded the album between November 1967 and February 1968, with sessions taking place in London and the Indian city of Bombay. Following his Indian-styled compositions for the Beatles since 1966, he used the film soundtrack to further promote Indian classical music by introducing rock audiences to musical instruments that were relatively little-known in the West – including shehnai, sarod and santoor. During the sessions, Harrison recorded many other pieces that appeared in Wonderwall but not on the soundtrack album, and the Beatles’ song The Inner Light also originated from his time in Bombay. Although the album’s release in November 1968 marked the end of Harrison’s direct involvement with Indian music, it inspired his later collaborations with Ravi Shankar, including the 1974 Music Festival from India.

For the front cover of Wonderwall Music (, American artist Bob Gill painted a picture in the style of Belgian surrealist René Magritte. The painting shows a formally dressed man “separated by a huge red brick wall from a group of happy bathing Indian maidens”, Bruce Spizer writes. Apple executive Derek Taylor, whom Harrison had invited to help run the Beatles’ label in early 1968, later recalled of Gill’s submission: “It was a nice painting but missed the essence of hope.” To Gill’s chagrin, Harrison requested that a brick be removed from the wall, because he deemed it important to “give the fellow on the other side a chance, just as the Jack MacGowran character had a chance [in the film]”.

For the back cover, Harrison chose a photo of part of the Berlin Wall, which designers John Kelly and Alan Aldridge then manipulated and mirrored to represent a corner. Taylor describes the result as innovative for its time, with the wall made to look “proud and sharp as the prow of a liner”.

The sleeve was designed so that the rear face appeared upside down relative to the front. In America, some copies of the LP had the Berlin Wall image mistakenly printed on the front, which made for “a less than exciting cover to be sure”, in Madinger and Easter’s opinion. Included on the LP’s sleeve insert was a black-and-white photograph of Harrison taken by Astrid Kirchherr (credited as Astrid Kemp, since 1967, Kirchherr married English drummer Gibson Kemp).

by Jade Reason

La vía del estilo

Art still has truth. Take refuge there.

Tales from Tinseltown...recording them now...I'll let you know when it's story time.

My Work My Art My Show - new school Sex and the City

All my words that are fit to print (and other's too!)

Making Life more Beautiful

Tulio Silva

Life, Leisure, Luxury

MYTHS AND HISTORIES OF A RELUCTANT BLOGGER

All my aimless thoughts, ideas, and ramblings, all packed into one site!

Meaning in Being. You be you.

Poetry, musings and sightings from where the country changes

Cooking is personalization.

Creativity is within us all