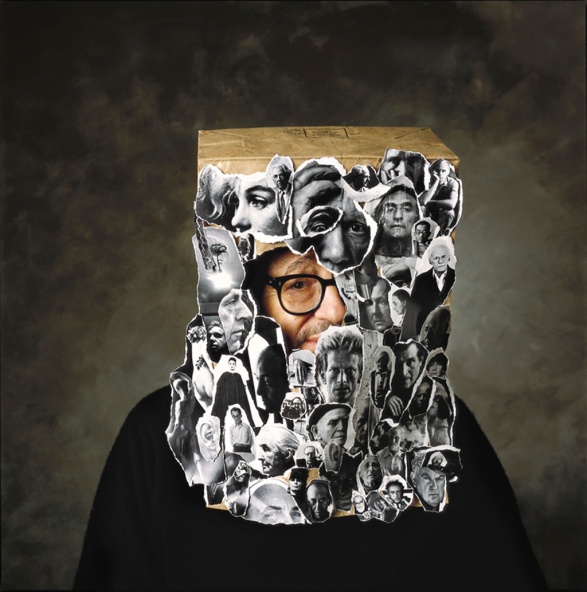

Jorge Luis Borges at the Hotel des Beaux Arts, Paris, in 1969. Photo: José María Pepe Fernández.

Jorge Luis Borges at the Hotel des Beaux Arts, Paris, in 1969. Photo: José María Pepe Fernández.

The Thousand and One Nights

Jorge Luis Borges

1980

tr. Eliot Weinberger, 1984

The Georgian Review (Fall 1984): 564-574.

A major event in the history of the West was the discovery of the East. It would be more precise to speak of a continuing consciousness of the East, comparable to the presence of Persia in Greek history. Within this general consciousness of the Orient — something vast, immobile, magnificent, incomprehsible — there were certain high points, and I would like to mention a few. This seems to me the best approach to a subject I love so much, one I have loved since childhood, The Book of the Thousand and One Nights or, as it is called in the English version — the one I first read — The Arabian Nights, a title that is not without mystery, but is less beautiful.

I will mention a few of these high points. First, the nine books of Herodotus, and in them the revelation of Egypt, far-off Egypt. I say “far-off” because space was measured by time, and the journey was hazardous. For the Greeks, the Egyptian world was older and greater, and they felt it to be mysterious.

We will examine later the words Orient and Occident, East and West, which we cannot define, but which are true. They remind me of what St. Augustine said about time: “What is time? If you don’t ask me I know; but if you ask me I don’t know.” What are East and the West? If you ask me, I don’t know. We must settle for approximations.

Let us look at the encounters, the campaigns, and the wars of Alexander, who conquered Persia and India and who died finally in Babylonia, as everyone knows. This was the first great meeting with the East, and an encounter that so affected Alexander that he ceased to be Greek and became partly Persian. The Persians have now incorporated him into their history — Alexander, who slept with a sword and the Iliad under his pillow. We will return to him later, but since we are mentioning Alexander, I would like to recall a legend that may be of interest to you.

Alexander does not die in Babylonia at age thirty-three. He is separated from his men and wanders through the deserts and forests, and at last he sees a great light. It is a bonfire, and it is surrounded by warriors with yellow skin and slanted eyes. They do not know him, but they welcome him. As he is at heart a soldier, he joins in battles in a geography that is unknown to him. He is a soldier: the causes do not matter to him, but he is willing to die for them. The years pass, and he has forgotten many things. Finally the day arrives when the troops are paid off, and among the coins there is one that disturbs him. He has it in the palm of his hand, and he says: “You are an old man; this is the medal that was struck for the victory of Arbela when I was Alexander of Macedon.” At that moment he remembers his past, and he returns to being a mercenary for the Tartars or Chinese or whoever they were.

That memorable invention belongs to the poet Robert Graves. To Alexander had been prophesied the dominion of the East and the West. The Islamic countries still honor him under the name Alexander the Two-Horned, because he ruled the two horns of East and West.

Let us look at another example of this great — and not infrequently, tragic — dialogue between East and West. Let us think of the young Virgil, touching a piece of printed silk from a distant country. The country of the Chinese, of which he only knows that it is far-off and peaceful, at the further reaches of the Orient. Virgil will remember that silk in his Georgics, that seamless silk, with images of temples, emperors, rivers, bridges, and lakes far removed from those he knew.

Another revelation of the Orient is that admirable book, the Natural History of Pliny. There he speaks of the Chinese, and he mentions Bactria, Persia, and the India of King Porus. There is a poem of Juvenal I read more than forty years ago, which suddenly comes to mind. In order to speak of a far-off place, Juvenal says, “Ultra Auroram et Gangem,” beyond the dawn and the Ganges. In those four words is, for us the East. Who knows if Juvenal felt it as we do? I think so. The East has always held a fascination for the people of the West.

Proceeding through history, we reach a curious gift. Possibly it never happened; it has sometimes been considered a legend. Harun al-Rashi, Aaron the Orthodox, sent his counterpart Charlemagne an elephant. Perhaps it was impossible to send an elephant from Baghdad to France, but that is not important. It doesn’t hurt to believe it. That elephant is a monster. Let us remember that the word monster does not mean something horrible. Lope de Vega was called a “Monster of Nature” by Cervantes. That elephant must have been something quite strange for the French and for the Germanic king Charlemagne. (It is sad to think that Charlemagne could not have read the Chanson de Roland, for he spoke some Germanic dialect.)

They sent the elephant, and that word elephant reminds us that Roland sounded the olifant, the ivory trumpet that got its name precisely because it came from the tusk of an elephant. And since we are speaking of etymologies, let us recall that the Spanish word alfil, the bishop in the game of chess, means elephant in Arabic and has the same origin as marfil, ivory. Among Oriental chess pieces I have seen an elephant with a castle and a little man. That piece was not the rook, as one might think from the castle, but rather the bishop, the alfil, or elephant.

In the Crusades, the soldiers returned and brought back memories. They brought memories of lions, for example. We have the famous crusader Richard the Lion-Hearted. The lion that entered into heraldry is an animal from the East. This list should not go on forever, but let us remember Marco Polo, whose book is a revelation of the Orient — for a long time it was the major source. The book was dictated to a friend in jail, after the battle in which the Venetians were conquered by the Genoese. In it, there is the history of the Orient, and he speaks of Kublai Khan, who will reappear in a certain poem by Coleridge.

In the fifteenth century in the city of Alexandria, the city of Alexander the Two-Horned, a series of tales was gathered. Those tales have a strange history, as it is generally believed. They were first told in India, then in Persia, then in Asia Minor, and finally were written down in Arabic and compiled in Cairo. They became The Book of the Thousand and One Nights.

I want to pause over the title. It is one of the most beautiful in the world . . . . I think its beauty lies in the fact that for us the word thousand is almost synonymous with infinite. To say a thousand nights is to say infinite nights, countless nights, endless nights. To say a thousand and one nights is to add one to infinity. Let us recall a curious English expression: instead of forever, they sometimes say forever and a day. A day has been added to forever. It is reminiscent of a line of Heine, written to a woman: “I will love you eternally and even after.”

The idea of infinity is consubstantial with The Thousand and One Nights.

In 1704, the first European version was published, the first of the six volumes by the French Orientalist Antoine Galland. With the Romantic movement, the Orient richly entered the consciousness of Europe. It is enough to mention two great names: Byron, more important for his image than for his work, and Hugo, the greatest of them all. By 1890 or so, Kipling could say: “Once you have heard the call of the East, you will never hear anything else.”

Let us return for a moment to the first translation of The Thousand and One Nights. It is a major event for all European literature. We are in 1704, in France. It is the France of the Grand Siècle; it is the France where literature is legislated by Boileau, who dies in 1711 and never suspects that all his rhetoric is threatened by that splendid Oriental invasion.

Let us think about the rhetoric of Boileau, made of precautions and prohibitions, of the cult of reason, and of that beautiful line of Fénelon: “Of the operations of the spirit, the least frequent is reason.” Boileau, of course, wanted to base poetry on reason.

We are speaking in the illustrious dialect of Latin we call Spanish, and it too is an episode of that nostalgia, of that amorous and at times bellicose commerce between Orient and Occident, for the discovery of America is due to the desire to reach the Indies. We call the people of Montezuma and Atahualpa Indians precisely because of this error, because the Spaniards believed they had reached the Indies. This little lecture is part of that dialogue between East and West.

As for the word Occident, we know its origin, but that does not matter. Suffice to say that Western culture is not pure in the sense that it exists entirely because of Western efforts. Two nations have been essential for our culture: Greece (since Rome is a Hellenistic extension) and Israel, an Eastern country. Both are combined into what we call Western civilization. Speaking of the revelations of the East, we must also remember the continuing revelation that is the Holy Scripture. The fact is reciprocal, now that the West influences the East. There is a book by a French author called The Discovery of Europe by the Chinese — that too must have occurred.

The Orient is the place where the sun comes from. There is a beautiful German word for the East, Morgenland, land of evening. You will recall Spengler‘s Der Untergang des Abendlandes, that is, the downward motion of the land of evening, or, as it is translated more prosiacally, The Decline of the West. I think that we must not renounce the word Orient, a word so beautiful, for within it, by happy chance, is the word oro,gold. In the word Orient we feel the word oro, for when the sun rises we see a sky of gold. I come back to that famous line of Dante: “Dolce color d’oriental zaffiro.” The word oriental here has two meanings: the Oriental sapphire, which comes from the East, and also the gold of morning, the gold of that first morning in Purgatory.

What is the Orient? If we attempt to define it in a geographical way, we encounter something quiet strange: part of the Orient, North Africa, is in the West, or what for the Greeks and Romans was the West. Egypt is also the Orient, and the lands of Israel, Asia Monor, and Bactria, Persia, India — all of those countries that stretch further and further and have little in common with one another. Thus, for example, Tartary, China, Japan — all that is our Orient. Hearing the word Orient, I think we all think, first of all, of the Islamic Orient, and by extension the Orient of northern India.

Such is the primary meaning it has for us, and this is the product of The Thousand and One Nights. There is something we feel as the Orient, something I have not felt in Israel but have felt in Granada and in Córdoba. I have felt the presence of the East, and I don’t know if I can define it; perhaps it’s not worth it to define something we feel so instinctively. The connotations of that word we owe to The Thousand and One Nights. It is our first thought; only later do we think of Marco Polo or the legends of Prester John, of those rivers of sand with fishes of gold. First we think of Islam.

Let us look at the history of the book, and then at the translations. The origin of the book is obscure. We may think of the cathedrals, miscalled Gothic, that are the works of generations of men. But there is an essential difference: the artisans and craftsmen of the cathedrals knew what they were making. In contrast, The Thousand and One Nights appears in a mysterious way. It is the work of thousands of authors, and none of them knew that he was helping to construct this illustrous book, one of the most illustrious books in all literature (and one more appreciated in the West than in the East, so they tell me).

Now, a curious note that was transcribed by the Baron von Hammer-Purgstall, an Orientalist cited with admiration by both Lane and Burton, the two most famous English translators of The Thousand and One Nights. He speaks of certain men he calls confabulatores nocturni, men of the night who tell stories, men whose profession it is to tell stories during the night. He cites an ancient Persian text which states that the first person to hear such stories told, who gathered the men of the night to tell stories in order to ease his insomnia, was Alexander of Macedon.

Those stories must have been fables. I suspect that the enchantment of fables is not in their morals. What enchanted Aesop or the Hindu fabulists was to imagine animals that were like little men, with their comedies and tragedies. The idea of the moral proposition was added later. What was important was the fact that the wolf spoke with the sheep and the ox with the ass, or the lion with the nightingale.

We have Alexander of Macedon hearing the stories told by these anonymous men of the night, and this profession lasted for a long time. Lane, in his book Account of the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians, says that as late as 1850 storytellers were common in Cairo. There were some fifty of them, and they often told stories from The Thousand and One Nights.

We have a series of tales. Those from India, which form the central core (according to Burton and to Cansinos-Asséns, author of an excellent Spanish version) pass on to Persia; in Persia they are modified, enriched, and Arabized. They finally reach Egypt at the end of the fifteenth century, and the first compilation is made. This one leads to another, apparently a Persian version: Hazar Afsana, the thousand tales.

Why were there first a thousand and later a thousand and one? I think there are two reasons. First, there was the superstition — and superstition is very important in this case — that even numbers are evil omens. They then sought an odd number and luckily added and one. If they had made it nine hundred and ninety-nine we would have felt that there was a night missing. This way we feel that we have been given something infinite, that we have received a bonus — another night.

We know that chronology and history exist, but they are primarily Western discoveries. There are no Persian histories of literature or Indian histories of philosophy, nor are there Chinese histories of Chinese liberature, because they are not interested in the succession of facts. They believe that literature and poetry are eternal processes. I think they are basically right. For example, the title, The Thousand and One Nights would be beautiful even if it were invented this morning. If it had been made today we would think what a lovely title, and it is lovely not only because it is beautiful (as beautiful as Lugones‘ Los crepúsculos del jardín: The Twilights of the Garden) but because it makes you want to read the book.

One feels like getting lost in The Thousand and One Nights, one knows that entering that book one can forget one’s own poor human fate; one can enter a world, a world made up of archetypal figures but also of individuals.

In the title The Thousand and One Nights there is something very important: the suggestion of an infinite book. It practically is. The Arabs say that no one can read The Thousand and One Nights to the end. Not for reasons of boredom: one feels the book is infinite.

At home I have the seventeen volumes of Burton’s version. I know I’ll never read all of them, but I know that there the nights are waiting for me; that my life may be wretched but the seventeen volumes will be there; there will be that species of eternity, The Thousand and One Nights of the Orient.

How does one define the Orient (not the real Orient, which does not exist)? I would say that the notions of East and West are generalizations, but that no individual can feel himself to be Oriental. I suppose that a man feels himself to be Persian or Hindu or Malaysian, but not Oriental. In the same way, no one feels himself to be Latin American: we feel ourselves to be Argentines or Chileans. It doesn’t matter; the concept does not exist.

What is the Orient, then? It is above all a world of extremes in which people are very unhappy or very happy, very rich or very poor. A world of kings, of kings who do not have to explain what they do. Of kings who are, we might say, as irresponsible as gods.

There is, moreover, the notion of hidden treasures. Anybody may discover one. And the notion of magic, which is very important. What is magic? Magic is unique causality. It is the belief that besides the causal relations we know, there is another causal relation. That relationship may be due to accidents, to a ring, to a lamp. We rub a ring, a lamp, and a genie appears. That genie is a slave who is also omnipotent and who will fulfill our wishes. It can happen at any moment.

Let us recall the story of the fisherman and the genie. The fisherman has four children and is poor. Every morning he casts his net from the banks of a sea. Already the expression a sea is magical, placing us in a world of undefined geography. The fisherman doesn’t go down the the sea, he goes down to a sea and casts his net. One morning he casts and hauls it in three times: he hauls in a dead donkey, he hauls in broken pots — in short, useless things. He casts his net a fourth time — each time he recites a poem — and the net is very heavy. He hopes it will be full of fish, but what he hauls in is a jar of yellow copper, sealed with the seal of Suleiman (Solomon). He opens the jar, and a thick smoke emerges. He thinks of selling the jar to the hardware merchants, the smoke rises to the sky, condenses, and forms the figure of a genie.

What are these genies? They are related to a pre-Adamite creation — before Adam, inferior to men, but they can be gigantic. According to the Moslems, they inhabit all of space and are invisible and impalpable.

The genie says, “All praises to God and Solomon His Prophet.” The fisherman asks why he speaks of Solomon, who died so long ago; today His Prophet is Mohammed. He also asks him why he is closed up in the jar. The genie tells him that he is one of those who rebelled against Solomon, and that Solomon enclosed him in the jar, sealed it, and threw it to the bottom of the sea. Four hundred years passed, and the genie pledged that whoever liberated him would be given all the gold in the world. Nothing happened. He swore that whoever liberated him, he would teach the song of the birds. The centuries passed, and the promises multiplied. Finally he swore that he would kill whoever freed him. “Now I must fulfill my promise. Prepare to die, my savior!” That flash of rage makes the genie strangely human, and perhaps likable.

The fisherman is terrified. He pretends to disbelieve the story, and he says: “What you have told me cannot be true. How could you, whose head touches the sky and whose feet touch the earth, fit into that tiny jar?” The genie answers: “Man of little faith, you will see.” He shrinks, goes back into the jar, and the fisherman seals it up.

The story continues, and the protagonist becomes not a fisherman but a king, then the king of the Black Islands, and at the end everything comes together. It is typical of The Thousand and One Nights. We may think of those Chinese spheres in which there are other spheres, or of Russian dolls. We encounter something similar in Don Quixote but not taken to the extremes of The Thousand and One Nights. Moreover, all of this is inside a vast central tale which you all know: that of the sultan who has been deceived by his wife and who, in order never to be deceived again, resolves to marry every night and kill the woman the following morning. Until Scheherazade pledges to save the others and stays alive by telling stories that remain unfinished. They spend a thousand and one nights together, and in the end she produces a son.

Stories within stories create a strange effect, almost infinite, a sort of vertigo. This has been imitated by writers ever since. The “Alice” books of Lewis Carroll or his novel Sylvia and Bruno, where there are dreams that branch out and multiply.

The subject of dreams is a favorite of The Thousand and One Nights. For example, the story of the two dreamers. A man in Cairo dreams that a voice orders him to go to Isfahan in Persia, where a treasure awaits him. He undertakes the long and difficult voyage and finally reaches Isfahan. Exhausted, he stretches out in the patio of a mosque to rest. Without knowing it he is among thieves. They are all arrested, and the cadi asks him why he has come to the city. The Egyptian tells him. The cadi laughs until he shows the back of his teeth and says to him: “Foolish and gullible man, three times I have dreamed of a house in Cairo, behind which is a garden, and in the garden a sundial, and then a fountain and a fig tree, and beneath the fountain there is a treasure. I have never given the least credit to this lie. Never return to Isfahan. Take this money and go.” The man returns to Cairo. He has recognized his own house in the cadi’s dream. He digs beneath the fountain and finds the treasure.

In The Thousand and One Nights there are echoes of the West. We encounter the adventures of Ulysses, except that Ulysses is called Sinbad the Sailor. The adventures are at times identical: for example, the story of Polyphemus.

To erect the palace of The Thousand and One Nights it took generations of men, and those men are our benefactors, as we have inherited this inexhaustible book, this book capable of so much metamorphosis. I say so much metamorphosis because the first translation, that of Galland, is quite simple and is perhaps the most enchanting of them all, the least demanding on the reader. Without this first text, as Captain Burton said, the later versions could not have been written.

Galland publishes his first volume in 1704. It produces a sort of scandal, but at the same time it enchants the rational France of Louis XIV. When we think of the Romantic movement, we usually think of dates that are much later. But it might be said that the Romantic movement begins at that moment when someone, in Normandy or in Paris, reads The Thousand and One Nights. He leaves the world legislated by Boileau and enters the world of Romantic freedom.

The other events come later: the discovery of the picaresque novel by the Frenchman Le Sage; the Scots and English ballads published by Percy around 1750; and, around 1798, the Romantic movement beginning in England with Coleridge, who dreams of Kublai Khan, the protector of Marco Polo. We see how marvelous the world is and how interconnected things are.

Then come the other translations. The one by Lane is accompanied by an encyclopedia of the customs of the Moslems. The anthropological and obscene translation by Burton is written in a curious English partly derived from the fourteenth century, an English full of archaisms and neologisms, an English not devoid of beauty but which at times is difficult to read. Then the licensed (in both senses of the word) version of Doctor Mardrus, and a German version, literal but without literary charm, by Littmann. Now, happily, we have a Spanish version by my teacher Rafael Cansinos-Asséns. The book has been published in Mexico; it is perhaps the best of all the versions, and it is accompanied by notes.

The most famous tale of The Thousand and One Nights is not found in the original version. It is the story of Aladdin and the magic lamp. It appears in Galland’s version, and Burton searched in vain for an Arabic or Persian text. Some have suspected Galland forged the tale. I think the word forged is unjust and malign. Galland had as much right to invent a story as did those confabulatores nocturni. Why shouldn’t we suppose that after having translated so many tales, he wanted to invent one himself, and did?

The story does not end with Galland. In his autobiography De Quincey says that, for him, there was one story in The Thousand and One Nights that was incomparably superior to the others, and that was the story of Aladdin. He speaks of the magician of Magrab who comes to China because he knows that there is the one person capable of exhuming the marvelous lamp. Galland tells us that the magician was an astrologer, and that the stars told him he had to go to China to find the boy. De Quincey, who had a wonderfully inventive memory, records a completely different fact. According to him, the magician had put his ear to the ground and had heard the innumerable footsteps of men. And he had distinguished, from among the footsteps, those of the boy destined to discover the lamp. This, said De Quincey, brought him to the idea that the world is made of correspondences, is full of magic mirrors — that in small things is the cipher of the large. The fact of the magician putting his ear to the ground and deciphering the footsteps of Aladdin appears in none of these texts. It is an invention of the memory or the dreams of De Quincey.

The Thousand and One Nights has not died. The infinite time of the thousand and one nights continues its course. At the beginning of the eighteenth century the book was translated; at the beginning of the nineteenth (or end of the eighteenth) De Quincey remembered it another way. The Nights will have other translators, and each translator will create a different version of the book. We may almost speak of the many books titles The Thousand and One Nights: two in French, by Galland and Mardrus; three in English, by Burton, Lane, and Paine; three in German, by Henning, Littmann, and Weil; one in Spanish by Cansinos-Asséns. Each of these books is different, because The Thousand and One Nights keeps growing or recreating itself. Robert Louis Stevenson‘s admirable New Arabian Nights takes up the subject of the disguised prince who walks through the city accompanied by his vizier and who has curious adventures. But Stevenson invented his prince, Florizel of Bohemia, and his aide-de-camp, Colonel Geraldine, and he had them walk through London. Not a real London, but a London similar to Baghdad; not the Baghdad of reality, but the Baghdad of The Thousand and One Nights.

There is another author we must add: G. K. Chesterton, Stevenson’s heir. The fantastic London in which occur the adventures of Father Brown and of The Man Who Was Thursday would not exist if he hadn’t read Stevenson. And Stevenson would not have written his New Arabian Nights if he hadn’t read The Arabian Nights. The Thousand and One Nights is not something which has died. It is a book so vast that it is not necessary to have read it, for it is a part of our memory — and also, now, a part of tonight.