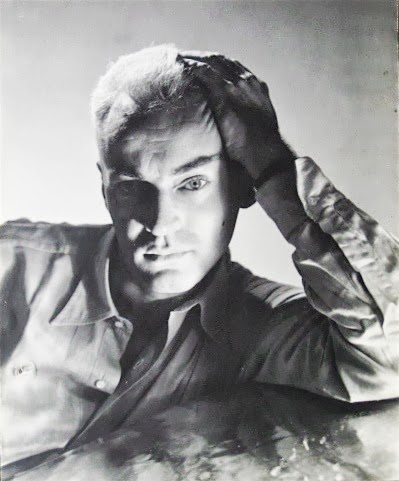

Photographs by Robert Mapplethorpe from 1983 to circa 1986

Photographs by Robert Mapplethorpe from 1983 to circa 1986

“Robert was not a literal person.

Everything he saw was an ambiguous shade of something else.

He was a metaphorical person. The irony was he took photography, which is a literal person’s perfect way to show life in snapshots, and raised the single frame to a metaphor.

A Mapplethorpe lily is not a lily is not a lily*.

This is trick photography shot by a trickster.

Now you see it.

Now you don’t.

Now, if you’re lucky, you do.

Senator Jesse Helms never got it.

Helms probably thought that Robert’s drop-dead flowers, always actually more explicit than his human nudes, were, uh, flowers.

And not the sex organs of plants or, omigod, phallic and vaginal symbols!

Metaphor is a problem for fundamentalists clamming up the hard shell.

Robert captured the essence of flowers, figures, faces, and fetishes so resonantly on the literal level that the very perfection of the moment frozen in the single frame caused the very being of the object to suggest its own becoming… other.

That capturing of the suggestive instant of becoming ambiguous was his existential magic.

Elegant flowers become sexual organs,

The shadow of a flower becomes the horned god.

Sexuality becomes theology.

Face becomes mask.

The mirror becomes window.

Life becomes death.

The cross becomes the crown.

Light becomes dark.

The looking glass makes the way out become the way in: the anal insertions.

This spinning ambiguity causes fear in the literal-minded who look at his single-shot metaphors…

…He intended his stills to be “moving” pictures, photographs that “moved” the viewer, through assault if necessary, for the viewer’s own good, the way one slaps someone who is hysterical.

Every Mapplethorpe photograph is a single frame in a movie, which, if it existed, would be a series of dissolves:

The lily dissolves to the genitalia,

The face to the skull,

The skull to the lily.

Although versed in film and video, Robert consciously kept with the discipline of the single-frame still camera.

Robert was a Platonist: he saw the real and he saw the ideal.”

Mapplethorpe: Assault With a Deadly Camera

Jack Fritscher

*Praraphrase of Gertrude Stein’s sentence “Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose.”