“! O friendship, how piercing are your darts..”

Virginia Woolf

The Waves

We know from correspondence with Federico García Lorca and other friends of the painter such as Sebastià Gasch that Salvador Dalí used to refer to the now-disappeared painting as the Apparatus Forest, while on this oil painting we can clearly read in the lower left-hand corner: Etude pour “Le miel est plus douce que la sang” [sic]. The highly poetical expression of the title takes its inspiration, as Dalí explains in The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, from words used by Lídia de Cadaqués: “[…] Lídia began to pluck it, and soon the whole room was covered in feathers. When this operation was over, she cleaned the chicken, and with her fingers dripping with blood, she began to pull out its viscera which she arranged neatly on a separate dish on the crystal table, where I had laid a very expensive book of facsimiles of the drawings of Giovanni Bellini. Observing that I jumped up anxiously to remove the book against the possibility of splashing, Lydia smiled bitterly, and said, “Blood does not spot” and then she immediately added this sentence, which a malicious expression in her eyes charged with erotic hidden meanings, “Blood is sweeter than honey. I,” she went on, “am blood, and honey is all the other women! My sons…” (this she added in a low voice) “at this moment are against blood and are running after honey.’”

The Rotting Donkey, Salvador Dalí, 1928

The Rotting Donkey, Salvador Dalí, 1928

This work is also of great interest due to its being the study for a now-disappeared painting called Honey is Sweeter than Blood, dating from 1927. In the Study we might particularly note the same iconographic features that make the finished work so special: the apparatuses, the severed head, the blood, the rotting donkey, etc., features that refer us back to the painter’s “new aesthetic” and in which we can observe the first clear references to Surrealism. This “new aesthetic” is the one formally announced in some of his articles published in L’Amic de les Arts, such as Sant Sebastià or La meva amiga i la platja, and also discussed with his friend the poet García Lorca in the letters they exchanged over that period.

We are likewise aware that Dalí’s pictorial work cannot be separated from his written work. This characteristic trait of the painter’s trajectory arose at this very time, while he was gestating Honey is Sweeter than Blood and therefore engaged in this study for that work. These paintings and the text are indicative of a turning point in Dalí’s art following a period of several years in which he had been experimenting with a broad diversity of modern and contemporary styles.

Study for Honey is Sweeter than Blood, Salvador Dalí, 1926. Dalí placed a likeness of Lorca’s head, with its neck severed, eyes wide open, and a trickle of blood seeping from its mouth near the donkey.

Study for Honey is Sweeter than Blood, Salvador Dalí, 1926. Dalí placed a likeness of Lorca’s head, with its neck severed, eyes wide open, and a trickle of blood seeping from its mouth near the donkey.

Apparatus and Hand (1927)

Apparatus and Hand (1927)

It is a landmark work that, along with Little Ashes and Apparatus and Hand represents Dalí’s first mature articulation of the neurotic dream-like imagery for which he is best known.

Honey is Sweeter than Blood (1926)

Honey is Sweeter than Blood (1926)

Aside from Parisian Surrealism and Brueghel however, the primary, overriding and determining influence on both Honey is Sweeter than Blood and Study for Honey is Sweeter than Blood was that of Dalí’s closest friend and confidant at this time, the poet Frederico Garcia Lorca. Lorca had spent the month of July with Dalí in Cadaqués and it was he who gave these works their original title of The Wood of Gadgets while also seeming to have inspired their later title writing to Dalí about the headless female corpse that appears in both paintings that, ‘the dissected woman is the most beautiful poem about blood you can create’ (Frederico Garcia Lorca, letter to Dalí quoted in Félix Fanés Salvador Dalí: The Construction of the Image 1925-1930 , London, 2007, p. 67).

As stated before, Honey is Sweeter than Blood and the study for it are thus works that mark a process of stylistic change in which there appear some elements from the previous period, such as the severed heads that reveal to us the stamp of his new classicism, and particularly the influence of Pablo Picasso (Table in front of the Sea, 1926; Still Life by Moonlight, 1926; Composition with Three Figures; Neo-Cubist Academy, 1926) ; objects that become “pieces of apparatus” and that show Dalí’s interest in “machinism”. We also have the initial influences of other contemporary artists such as Joan Miró, Yves Tanguy and particularly Giorgio de Chirico.

The phrase ‘honey is sweeter than blood’ is one that seems to have haunted Dalí at this time. It crops up in numerous instances in his life, its most notable appearance perhaps being in his book The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí where as Dawn Ades has pointed out, Dalí describes the solitary pleasure of masturbation as ‘sweeter than honey’ while Lorca is said to have regarded sexual intercourse as a fearful ‘jungle of blood’ (D. Ades, Dalí, The Centenary Retrospective, London, 2005, p. 90). Fear of sex and the female along with the guilt, pleasure and addiction of masturbation are constant themes running through much of Dalí’s work of this period culminating in his 1929 paintings The Lugubrious Game and The Great Masturbator. Here, in Study for Honey is Sweeter than Blood such fetishistic motifs appear to be being born on the grey sandy beach-like plain cutting across the picture plain after the mutilation of a female corpse. It is Lorca’s face too that appears in this work as a decapitated double-sided head split in two and dissecting its mysterious diagonal borderline of sea-bed/plain and sea/sky.

At the heart of Lorca’s influence on these paintings however, stands his and Dalí’s shared obsession with Saint Sebastian. Already having informed much of Dalí’s work, the poet and the painter had developed a kind of coded language of association about the Saint, both recognising a part of themselves and each other in the story of this agonised martyr. Here, the cold, geometric machine-like needles or eye tacks puncturing the skin-like surface of the plain echo the nature of Sebastian’s martyrdom, while the split head seems to indicate a notion of a one-person duality in the form of Dalí and Lorca. In the final painting Dalí’s own visage appears on the head lying near the headless female corpse, while here, the sleeping head simultaneously bordering land and sky seems to anticipate the later soft sleeping heads able to transcend different realms and realities that Dalí frequently depicted in his work of the late 1920s and early ’30s. The veins and blood vessels visible in the top half of this head are echoed elsewhere in the picture on other truncated limbs, sprouting like a forest and also in what appears to be a small shoal of red fish swimming in the sky-like sea. This predisposition towards diagrammatic tree-like veins appears, like most the elements of this painting, in different but extended form in Apparatus and Hand and are derived from Dalí’s fascination with an illustration in an advertisement for a cure for varicose veins. With their coral-like forms, they also echo the use of red coral as a symbol of Christ’s blood in much Spanish religious painting.

Continuing the pervasive theme of a painful collusion between cold hard-edged mechanical form and soft, blood giving flesh, the central image of this picture is a decapitated female corpse with truncated arms and legs pouring blood into the soil which elsewhere seems to sprout into vein-like trees. This, along with the fetishistic image of a pair of disembodied breasts, perhaps another symbol of martyrdom referring to that of Saint Agatha, is also seemingly attacked by metallic needles and shown floating in the sky, while the arms of the corpse are seemingly depicted in a dual state of growth and decay on the beach. Reminiscent of a number of ‘headless women’ created by Max Ernst at this time, the mutilation of the female nude is a clear anti-art act and symbol, but also one celebrated here as an apparent source of life-blood and creativity. Nearby and in direct contrast, lies another anti-art symbol: one of the quintessential Dalínean images of putrefaction: the rotting donkey.

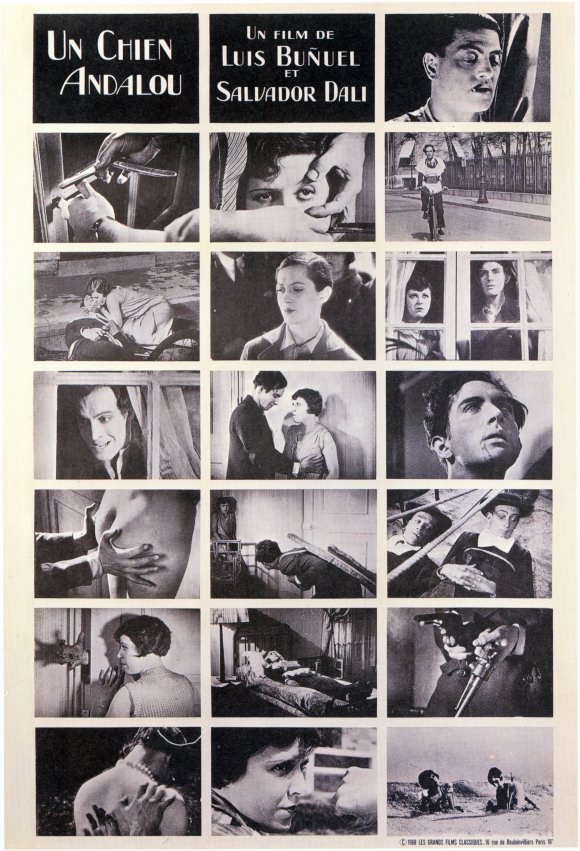

Perhaps most familiar now from its appearance in Dalí and Luis Buñuel‘s shocking first feature film Le Chien andalou, the image of the rotting donkey carcass surrounded by flies was a staple of many of Dalí’s pictures in the 1920s. A symbol of horror and repulsion and of the ugliness of reality with which avant-garde artists wished to challenge the complacency and bourgeois values of the traditional society they abhorred, the rotting donkey invokes a rich seam of satire known as ‘the putrefact’, that, as Dawn Ades has pointed out, was ‘mined in numerous drawings by the group in the Residencia de Estudiantes in Madrid which included Dalí, Lorca and Pepin Bello who was credited with inventing the term… The origin of the ‘putrefying’ donkey itself lies in a sentimental tale by the ‘arch putrefact’ as Dalí called him, the poet Juan Ramon Jiménez (whose) Platero y Yo recounts the life and death of a beloved donkey’ (ibid, p. 92). Here, as it was to appear in numerous other Dalí works, the artist has depicted this donkey decomposing into the soil of the painting surrounded by flies – another hard and horrifying anti-artistic symbol of the dark, nightmarish side of life, not usually associated with fine art.

As Dalí was also at pains to point out in an article he wrote about these works in 1928 however, all this horror takes place not in the real world, but within the magical realm of the picture plane. ‘We can verify,’ he wrote, ‘that the decapitated figures live their perfect, organic life, they rest in the shadow of the bloodiest vegetation without getting bloodstained, and they go on stretching out naked on the sharpest, spikiest surfaces of very special marble, without risk of death’ (Salvador Dalí, ‘Nous limits de la pintura’, 1928, quoted in Feliz Fanés Salvador Dalí: The Construction of the Image 1925-1930, London, 2007, p. 67).

René Magritte photographed by Bill Brandt, 1963

René Magritte photographed by Bill Brandt, 1963