The Infinite Recognition, René Magritte, 1963

The Infinite Recognition, René Magritte, 1963

A CLOUD IN TROUSERS

(Облако в штанах, Oblako v shtanakh)

Prologue

Your thought,

Fantasizing on a sodden brain,

Like a bloated lackey on a greasy couch sprawling,–

With my heart’s bloody tatters, I’ll mock it again.

Until I’m contempt, I’ll be ruthless and galling.

There’s no grandfatherly fondness in me,

There are no gray hairs in my soul!

Shaking the world with my voice and grinning,

I pass you by, — handsome,

Twentytwoyearold.

Gentle souls!

You play your love on the violin.

Crude ones beat it out on the drums violently.

But can you turn yourselves inside out, like me,

And become just two lips entirely?

Come and learn,–

You, decorous bureaucrats of angelic leagues!

Step out of those cambric drawing-rooms

And you, who can leaf your lips

Like a cook leafs the pages of her recipe books.

If you wish,–

I’ll rage on raw meat like a vandal

Or change into hues that the sunrise arouses,

If you wish,–

I can be irreproachably gentle,

Not a man, — but a cloud in trousers.

I refuse to believe in Nice blossoming!

I will glorify you regardless,–

Men, crumpled like bed-sheets in hospitals,

And women, battered like overused proverbs.

Part I

You think I’m delirious with malaria?

This happened.

In Odessa, this happened.

“I’ll come at four,” promised Maria.

Eight…

Nine…

Ten.

Soon, the evening,

Frowning

And Decemberish,

Left the windows

And vanished in dire darkness.

Behind me, I hear neighing and laughter

Of candelabras.

You wouldn’t recognize me if you knew me prior:

A bulk of sinews

Moaning,

Fidgeting.

What can such a clod desire?

But the clod desires many things.

Because for oneself it doesn’t matter

Whether you’re cast of copper

Or whether your heart is cold metal.

At night, you want to wrap your clamor

In something feminine,

Gentle.

And thus,

Enormous,

I hunch in the frame,

And with my forehead, I melt the window glass.

Will this love be

Tremendous or lame?

Will it sustain or pass?

A big one wouldn’t fit a body like this:

It must be a little love, —

a baby, sort of,

It shies away when the cars honk and hiss,

But adores the bells on the horse-tram.

I come face to face

With rippling rain,

Yet once more,

And wait

Splashed by city surf’s thundering roar.

Running amok with a knife outside,

Night caught up to him

And stabbed him,

Unseen.

The stroke of midnight

Fell like a head from a guillotine.

Silver raindrops on the windowpane

Were piling a grimace

And yelling.

It seemed like the gargoyles of Notre Dame

Started yelping.

Damn you!

Haven’t you had enough yet?

Cries will soon cut my throat all around.

I heard:

Softly,

Like a patient out of his bed,

A nerve leapt

Down.

At first,

He barely moved.

Then, apprehensive

And distinct,

He started prancing.

And now, he and another two,

Darted about, step-dancing.

On the ground floor, plaster was falling fast.

Nerves,

Big ones,

Little ones,–

Various!–

Galloped madly

Until, at last,

Their legs wouldn’t carry them.

Night oozed through the room and sank.

Stuck in slime, the eye couldn’t slither out of it.

Suddenly, doors started to bang

As if hotel’s teeth

Were chattering.

You entered,

Abrupt like “Take it!”

Mauling the suede gloves you carried,

And said:

“You know,–

I’m soon getting married.”

Les mariés dans le ciel de Paris, Marc Chagall, 1970

Les mariés dans le ciel de Paris, Marc Chagall, 1970

Get married then.

It’s all right,

I can handle it.

As you can see, I’m calm, of course!

Like the pulse

Of a corpse.

Remember?

You used to say:

“Jack London,

Money,

Love

And ardor,”–

I saw one thing only:

You were La Gioconda,

Which had to be stolen!

And someone stole you.

Again in love, I shall start gambling,

With fires illuminating the arch of my eyebrows.

And why not?

Sometimes, homeless ramblers

Will seek to find shelter in a burnt down house!

Part II

Glorify me!

The great ones are no match for me!

Upon everything that’s been done

I stamp the word “naught.”

As of now,

I have no desire to read.

Novels?

So what!

This is how books are made,

I used to think,–

Along comes a poet,

And opens his lips with ease.

Inspired, the fool simply begins to sing,–

Oh please!

It turns out:

Before they can sing with elation,

On their calloused feet they tramp for some time,

While brainless fishes of imagination

Are splashing and wallowing in the heart’s slime.

And while, hissing with rhymes, they boil

All the loves and the nightingales in a broth-like liquid,

The tongueless street merely squirms and coils,–

It has nothing to yell or even speak with.

In silence, the street dragged on the ordeal.

A scream stood erect on the gullet’s road.

While fat taxies and cabs were bristling still,

Wedged in the throat.

As if from consumption,

the trodden chest gasped for air.

The city, with gloom, blocked the road rather fast.

And when,–

Nevertheless! —

The street coughed up the strain onto the square

And pushed the portico off its throat, at last,

It seemed as if,

Accompanied by choirs of an archangel’s chorus,

Recently robbed, God would show us His heat!

But the street squatted down and yelled out coarsely:

“Let’s go eat!”

Krupps and Krupplets gather around

To paint menacing brows on the city,

While in the gorge,

Corpses of words are scatted about,–

Two live and thrive,–

“Swine”

And another one,–

I believe, “borsch”.

And poets,

Soaking in sobs and complaining,

Run from the street, resentful and sour:

“With those two words there’s no way to portray now

A beautiful lady,

And love

And a dew-covered flower!”

And after the poets,

Thousands of others stampeded:

Students,

Prostitutes,

Salesmen.

Why should I care about Faust?

In a fairy display of the fireworks’ loot,

He’s gliding with Mephistopheles

On the parquet of galaxies!

I know,–

A nail in my boot

Is more frightening than Goethe’s fantasies!

I am

The most golden-mouthed,

With every word giving

The body – a name-day,

And the soul – a rebirth,

I assure you:

Minutest speck of the living

Is worth more than I can ever do on this earth!

Haven’t you seen

A dog licking the hand that it’s being thrashed by?

I am laughed at

By the present-day tribe.

They’ve made

A dirty joke out of me.

But I can see crossing mountains of time,

Him, whom others can’t see.

Where men’s sight falls short,

Wearing the revolution’s thorny crown,

Walking at the head of a hungry horde,

The year 1916 is coming around.

And when

His advent announcing,

Joyful and proud,

You’ll step up to greet the savior,–

I will drag

My soul outside,

And trample it

So it spreads out!

And give it to you, red in blood, as a flag.

Ah, how and wherefrom

Did it come to this, –

Against luminous joy,

Dirty fists of madness,

Were raised in the air?

And

As in the Dreadnought’s downfall

With chocking spasms

Men jumped into the hatch,

Before the ship died,

The crazed Burlyuk crawled on, passing

Through the screaming gaps of his eye.

Almost bloodying his eyelids,

He emerged on his knees,

Stood up and walked

And in the passionate mood,

With tenderness, unexpected from one so obese,

He simply said:

“Good!”

It’s good when from scrutiny a yellow sweater

Hides the soul!

It’s good when

On the gibbet, in face of terror,

You shout:

“Drink Cocoa — Van Houten!”

This moment,

Like a Bengal light,

Crackling from the blast,

I wouldn’t exchange for anything,

Not for any money.

Clouded by cigar smoke,

And stretching like a liquor glass,

One could make out the drunken face of Severyanin.

How dare you call yourself a poet

And gray, like a quail, twitter away your soul!

When

With brass knuckles

This very moment

You have to split the world’s skull!

You,

With one thought alone in your head,

“Am I dancing with style?”

Look how happy I am

Instead,

I,–

A pimp and a fraud all the while.

From all of you,

Who soaked in love for plain fun,

Who spilled

Tears into centuries while you cried,

I’ll walk away

And place the monocle of the sun

Into my gaping, wide-open eye.

I’ll wear colorful clothes, the most outlandish,

And roam the earth To please and scorch the public,

And in front of me,

On a metal leash,

Napoleon will run like a little puppy.

Like a woman, quivering, the earth will lie down,

Wanting to give in, she will slowly slump.

Objects will come alive

And from all around,

Their lips will lisp:

“Yum-yum-yum-yum-yum!”

Suddenly,

Clouds

And other such stuff in the air

Stirred in some astonishing commotion,

As if workers in white, up there,

Declared a strike, all bitter and emotional.

Savage thunder peeked out of the cloud, irate.

Snorting with huge nostrils, it howled

And for a moment, the sky’s face bent out of shape,

Resembling the iron Bismarck’s scowl.

And someone,

Entangled in the clouds’ maze,

To the café, stretched out his hand now:

Both, tender somehow,

With a womanly face,

And at once, like a firing cannon.

Take your hands out of your pockets, wanderers.

Pick up a bomb, a knife or a stone

And if one happens to be armless,

Let him come to fight with his forehead alone!

Go on, starving,

Servile

And abused ones,

In this flea-swarming filth, do not rot!

Go on!

We’ll turn Mondays and Tuesdays

Into holidays, painting them with blood!

Remind the earth whom it tried to debase!

With your knives be rough!

The earth

Has grown fat like the mistress’ face,

Whom Rothschild had over-loved!

May flags flutter in the line of fire

As they do on holidays, with a flare!

Hey, street-lamps, raise the traitors higher,

Let their carcasses hang in the air.

I cursed,

Stabbed

And hit in the face,

Crawled after somebody,

Biting into their ribs.

In the sky, red like La Marseillaise,

Sunset gasped with its shuddering lips.

It’s insanity!

Not a thing will remain from the war.

Night will come,

Bite into you

And swallow you stale.

Look,–

Is the sky playing Judas once more,

With a handful of stars that were soaked in betrayal?

Slumped in the corner of the saloon, I sit,

Spilling wine on my soul and the floor,

And I see:

In the corner, round eyes are lit

And with them, Madonna bites the heart’s core.

Why bestow such radiance on this drunken mass?

What do they have to offer?

Can’t you see, once again,

They prefer Barabbas

Over the Man of Golgotha?

Maybe, deliberately,

In this human mash, not once

Do I wear a fresh-looking face.

I am,

Perhaps,

The handsomest of your sons

In the whole human race.

Give them,

The ones molded with delight,

A quick death already,

So that their children may grow up right;

Boys — into fathers

Girls — into pregnant ladies.

Like wise men, let new born babes

Grow gray with insight and thought

And they’ll come

To baptize infants with names

Of the poems I wrote.

Athletes glistened in the carriages on the street.

People burst

Overstuffed,

And their fat oozed out,

Like a muddy river, it streamed on the ground,

Together with juices from

A cud of old meat.

Maria!

How can I fit a tender word into bulging ears?

A bird

Sings for alms

With a hungry voice

Rather well,

A poet sings praises to Tiana all day,

But I,–

I’m made of flesh,

I’m a man,–

I ask for your body,

Like Christians pray:

“Give us this day

Our daily bread.”

I’ll climb out

Filthy (sleeping in gullies all night),

And into his ear, I’ll whisper

While I stand

At his side:

“Mister God, listen!

Isn’t it tedious

To dip your generous eyes into clouds

Every day, every evening?

Let’s, instead,

Start a festive merry-go-round

On the tree of knowledge of good and evil!

Omnipresent, you’ll be all around us!

From wine, all the fun will ensue

And for once, Peter will not be frowning,

He’ll perform the fast-paced dance, ki-ka-pu.

We’ll bring all the Eves back into Eden:

Order me

And I’ll go,–

From boulevards,

I’ll pick up all the pretty girls needed

And bring them to you!

Should I?

No?

You’re shaking your curly head coarsely?

You’re knitting your brows like you’re rough?

Do you think

That this

Winged one, close by,

Knows true meaning of love?

I too am an angel; used to be one before,–

With a sugar lamb’s eye, I stared at your faces,

But I don’t want to give presents to mares anymore,–

All the torture of Sevres that’s been made into vases.

Almighty, You created two hands,

And with care,

Made a head, and went down the list,–

But why did you make it

So that it pained

When one had to kiss, kiss, kiss?!

I thought that you were Great God, Almighty,

But you’re a miniature idol, — a dunce in a suit,

Bending over, I’m reaching

For the knife that I’m hiding

At the top of my boot.

You, swindlers with wings,

Huddle in fright!

Ruffle your shuddering feathers, rascals!

You, reeking of incense, I’ll open you wide,

From here all the way to Alaska.

Let me go!

You can’t stop me!

Whether I’m right or wrong

Makes no difference,

I will not be calmer.

Look,–

Stars were beheaded all night long

And the sky is again bloody with slaughter.

Hey you,

Heaven!

Take your hat off,

When you see me near!

Silence.

The universe sleeps.

Placing its paw

Under the black, star-infested ear.

Vladimir Mayakovsky

1914

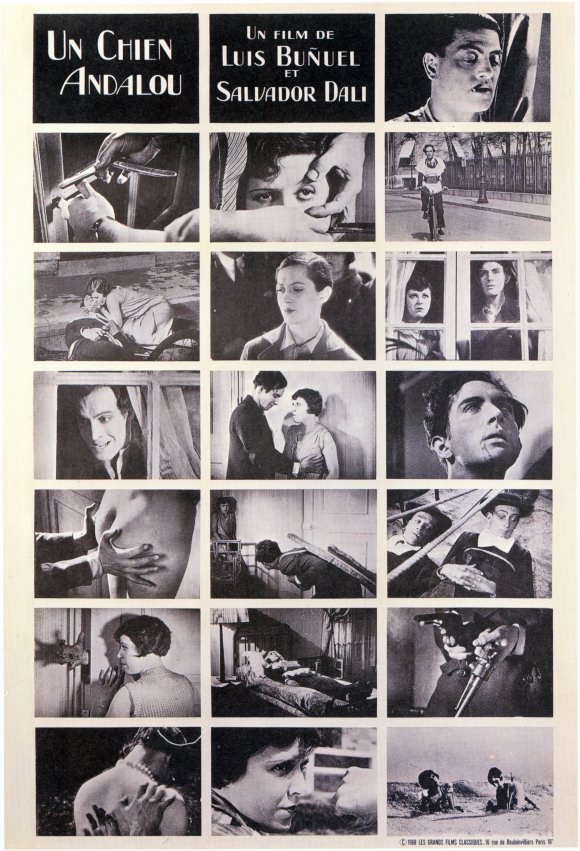

Originally titled The 13th Apostle (but renamed at the advice of a censor) Mayakovsky’s first major poem was written from the vantage point of a spurned lover, depicting the heated subjects of love, revolution, religion and art, taking the poet’s stylistic choices to a new extreme, linking irregular lines of declamatory language with surprising rhymes. It is considered to be a turning point in his work and one of the cornerstones of the Russian Futurist poetry.

The subject of Mayakovsky’s unrequited love was Maria Denisova whom he met in Odessa during the Futurists’ 1913 tour.Born in 1894 in Kharkov to a poor peasant family, Maria at the time resided with the family of her sister (whose husband Filippov was an affluent man) and was an art school student, learning sculpture. Vasily Kamensky described Denisova as “a girl of a rare combination of qualities: good looks, sharp intellect, strong affection for all things new, modern and revolutionary.” Mayakovsky fell in love instantly and gave her the nickname, Gioconda.

Mayakovsky started working of the poem (which he claim was born “as a letter, while on a train”) in the early 1914. He finished it in July 1915, in Kuokkala. Speaking at the Krasnaya Presnya Komsomol Palace in 1930, Mayakovsky remembered: “It started as a letter in 1913/14 and was first called “The Thirteenth Apostle”. As I came to see the censors, one of the asked me: Dreaming of doing a forced labour, eh? ‘By no means, I said, no such plans at all. So they erased six pages, as well as the title. Then, there’s the question about where the title has come from. Once somebody asked me how could I combine lyricism with coarseness. I replied: ‘Simple: you want me rabid, I’ll be it. Want me mild, and I’m not a man, a cloud in trousers.”