“The time-state of attainment eliminates so accurately the time-state of aspiration, that the actual seems the inevitable, and, all conscious intellectual effort to reconstitute the invisible and unthinkable as a reality being fruitless, we are incapable of appreciating our joy by comparing it with our sorrow.”

Samuel Beckett

Proust

Samuel Beckett. Photo by François-Marie Banier

Samuel Beckett. Photo by François-Marie Banier

Samuel Beckett wrote Proust in the summer of 1930, in response to a commission precipitated by Thomas MacGreevy, Charles Prentice, and Richard Aldington, during his stay at the École Normale in Paris. By the end of September, he delivered it by hand to Charles Prentice at Chatto and Windus. The book sold 2,600 copies by 1937, with the remaining 400 remaindered by 1941. In retrospect, Beckett dismissed it as written in “cheap flashy philosophical jargon.

The essay served double duty as its author’s aesthetic and epistemological manifesto, proclaiming on behalf of its ostensible subject: “We cannot know and we cannot be known.” In dense and allusive language, Beckett credited his current influences (notably Arthur Schopenhauer and Pedro Calderón de la Barca) and forecast his future preoccupations, reading them into the prose of Marcel Proust:

“The laws of memory are subject to the more general laws of habit. Habit is a compromise effected between the individual and his environment, or between the individual and his own organic eccentricities, the guarantee of a dull inviolability, the lightning-conductor of his existence. Habit is the ballast that chains the dog to his vomit. Breathing is habit. Life is habit. Or rather life is a succession of habits, since the individual is a succession of individuals; the world being a projection of the individual’s consciousness (an objectivation of the individual’s will, Schopenhauer would say), the pact must be continually renewed, the letter of safe-conduct brought up to date. The creation of the world did not take place once and for all time, but takes place every day. Habit then is the generic term for the countless treaties concluded between the countless subjects that constitute the individual and their countless correlative objects. The periods of transition that separate consecutive adaptations (because by no expedient of macabre transubstantiation can the grave-sheets serve as swaddling-clothes) represent the perilous zones in the life of the individual, dangerous, precarious, painful, mysterious and fertile, when for a moment the boredom of living is replaced by the suffering of being. (At this point, and with a heavy heart and for the satisfaction or disgruntlement of Gideans, semi and integral, I am inspired to concede a brief parenthesis to all the analogivorous, who are capable of interpreting the ‘Live dangerously,’ that victorious hiccough in vacuo, as the national anthem of the true ego exiled in habit. The Gideans advocate a habit of living—and look for an epithet. A nonsensical bastard phrase. An automatic adjustment of the human organism to the conditions of its existence has as little moral significance as the casting of a clout when May is or is not out; and the exhortation to cultivate a habit as little sense as an exhortation to cultivate a coryza.) The suffering of being: that is, the free play of every faculty. Because the pernicious devotion of habit paralyses our attention, drugs those handmaidens of perception whose co-operation is not absolutely essential.

Beckett went on to pinpoint his moral focus on the fundamental quandaries of human existence, disclaiming any involvement in social issues:

Here, as always, Proust is completely detached from all moral considerations. There is no right and wrong in Proust nor in his world. (Except possibly in those passages dealing with the war, when for a space he ceases to be an artist and raises his voice with the plebs, mob, rabble, canaille.) Tragedy is not concerned with human justice. Tragedy is the statement of an expiation, but not the miserable expiation of a codified breach of a local arrangement, organised by the knaves for the fools. The tragic figure represents the expiation of original sin, of the original and eternal sin of him and all his ‘soci malorum,’ the sin of having been born.

‘Pues el delito mayor

Del hombre es haber nacido.’

The final quotation is from Calderón de la Barca’s La vida es sueño (Life is a Dream), and ‘soci malorum’ is a quotation from Schopenhauer’s Studies in Pessimism.

In fact, the conviction that the world and man is something that had better not have been, is of a kind to fill us with indulgence towards one another. Nay, from this point of view, we might well consider the proper form of address to be, not Monsieur, Sir, mein Herr, but my fellow-sufferer, Soci malorum, compagnon de miseres!

In all his subsequent writings, Beckett continued to endorse this hamartiological conclusion; compare “The only sin is the sin of being born,” from a 1969 interview.

Château de Ferrières, the suburban Parisian mansion of Baron Guy de Rothschild and Marie-Hélène

Château de Ferrières, the suburban Parisian mansion of Baron Guy de Rothschild and Marie-Hélène Detail of a table with a fur dish, Mae West red lips and blue bread

Detail of a table with a fur dish, Mae West red lips and blue bread

the dîner des têtes surréalistes invitation with reversed writing inspired by a magritte sky

the dîner des têtes surréalistes invitation with reversed writing inspired by a magritte sky The Baroness Thyssen-Bornemizza & Guy Baguenault de Puchesse

The Baroness Thyssen-Bornemizza & Guy Baguenault de Puchesse Salvador Dalí and the Italian princess Maria Gabriella de Savoia

Salvador Dalí and the Italian princess Maria Gabriella de Savoia Charles de Croisset, Marisa Berenson snd Paul-Louis Weiller

Charles de Croisset, Marisa Berenson snd Paul-Louis Weiller Claude Lebon and Charlotte Aillaud

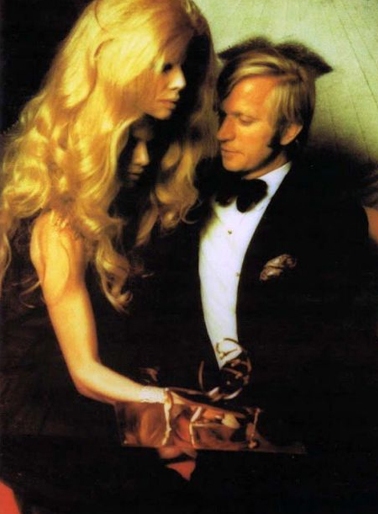

Claude Lebon and Charlotte Aillaud Hélène Rochas & François-Marie Banier

Hélène Rochas & François-Marie Banier For desert: a sugar made woman laying in a bed of roses

For desert: a sugar made woman laying in a bed of roses