Les Saltimbanques (The Acrobats), Pablo Picasso, 1905

Les Saltimbanques (The Acrobats), Pablo Picasso, 1905

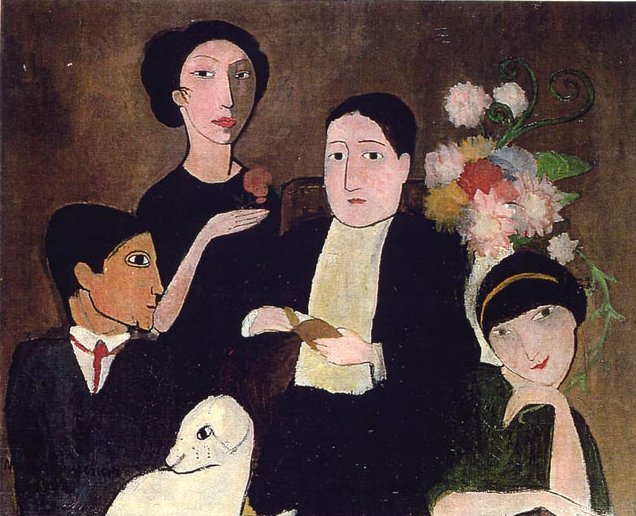

The Fifth Elegy is largely inspired by this Pablo Picasso‘s Rose Period painting, in which Picasso depicts six figures pictured “in the middle of a desert landscape and it is impossible to say whether they are arriving or departing, beginning or ending their performance.” Rilke depicted the six artists about to begin their performance, and that they were used as a symbol of “human activity … always travelling and with no fixed abode, they are even a shade more fleeting than the rest of us, whose fleetingness was lamented.” Further, Rilke in the poem described these figures as standing on a “threadbare carpet” to suggest “the ultimate loneliness and isolation of Man in this incomprehensible world, practicing their profession from childhood to death as playthings of an unknown will … before their ‘pure too-little’ had passed into ’empty too-much.'”

FIFTH DUINO ELEGY

For Frau Hertha Koenig

Who are these rambling acrobats,

less secure than even we;

twisted since childhood

(for benefit of whom?)

by an unappeasable will?

A will which wrings, bends,

swings, twists and catapults,

catching them when they fall

through slick and polished air

to a threadbare carpet worn

ever thinner by their leaping:

lost carpet of the great beyond,

stuck like a bandage to an earth

bruised by suburban skies.

Ensemble,

their bodies trace a vague

capital “C” for Creation…

captured by an inevitable grip

which bends even the mightiest,

as King Augustus the Strong

folded a pewter plate for laughs.

Around this center

the Rose of Looking

blossoms and sheds.

Around this pounding pestle,

this self pollinating pistle

producing petals of ennui,

blooms of customary apathy

speciously shine with

superfluous smiles.

There: the wrinkled, dried up Samson,

becomes, in old age, a drummer-

too small for the skin which looks

as though it once held two of him.

The other must be dead and buried

while this half fares alone,

deaf and somewhat addled

within the widowed skin.

There: the young man who seems

the very offspring of a union

between a stiff neck and a nun,

braced and buckled,

full of strength and

innocent simplicity.

O, you, children,

delivered to the infant Pain

as a toy to amuse it,

during some extended

illness of its childhood.

You, boy, discover

a hundred times a day

what green apples know,

dropping off a tree created

through mutual interactions

(coursing through spring,

summer and, swift as water,

fall, all in a flash)

to bounce, thud, upon the grave.

Sometimes, in fleeting glances

toward your seldom tender mother,

affection almost surfaces,

only to submerge as suddenly

beneath your face…a shy,

half-tried expression…

and then the man claps,

commanding you to leap again

and before any pain can

straddle your galloping heart,

your stinging soles outrace it,

chasing a brief pair of

actual tears to your eyes,

still blindly smiling.

O angel, pluck that

small flower of healing!

Craft a vessel to contain it!

Set it amongst joys not

yet vouchsafed us.

Upon that fair herbal jar,

in flowing, fancy letters,

inscribe: “Subrisio Saltat.”

…Smile of Acrobat…

And you, little sweetheart,

silently overslept by

the most exciting joys-

perhaps your skirthems

are happy in your stead,

or maybe the green metallic silk,

stretched tight by budding breasts,

feels itself sufficiently indulged.

You,

displaying, for all to see,

the fruit which tips the

swaying scales of balance,

suspended from the shoulders.

Where…O where is that place,

held in my heart, before they’d

all achieved such expertise,

were apt still to tumble asunder

like poorly fitted animals mating…

where the barbell still seems heavy,

where the discus wobbles and topples

from a badly twirled baton?

Then: Presto! in this

exasperating nowhere:

the unspeakable space appears where

purity of insufficiency transforms

into overly efficient emptiness.

Where the monumental bill of charges,

in final arbitration, totals zero.

Plazas, O plazas of Paris,

endless showcase, where

Madame Death the Milliner

twists and twines the

ribbons of restlessness,

designing ever new frills,

bows, rustles and brocades,

dyed in truthless colors,

to deck the trashy

winter hats of fate.

Angel! Were there an unknown place

where, upon an uncanny carpet, lovers

could disport themselves in ways

here inconceivable-daring ariel maneuvers

of the heart, scaling high plateaus of passion,

ladders leaning one against the other,

planted trembling upon the void…

Were there such a place, would their

performance prove convincing to an audience

of the innumerable and silent dead?

Would not these dead toss down their

final, hoarded, secret coins of joy,

legal tender of eternity, before the

couple smiling on that detumescent carpet,

fully satisfied?

Rainer Maria Rilke

Translated by Robert Hunter

Minotauromachy, Pablo Picasso, 1935

Minotauromachy, Pablo Picasso, 1935