Walton Ford was born in New York’s asphalt jungle at the end of the 60’s. He graduated from Rhode Island School of Design with a BFA degree. Though he first inspired to be a filmmaker, Ford would soon trade his camera for brushes, palettes, canvas and any other artistic supplies for printing and painting stills taken from wildlife.

Even as a toddler he felt fascinated by fauna. His parents encouraged his love of nature by taking him on Canadian getaways and to the Museum of Natural History in New York. Thanks to frequent visits to those places, his devotion for Akeley’s dioramas grew up. Biologist and sculptor Carl Ethen Akeley is considered the father of modern taxidermy.

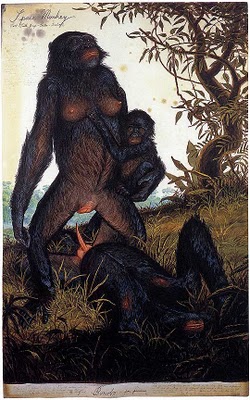

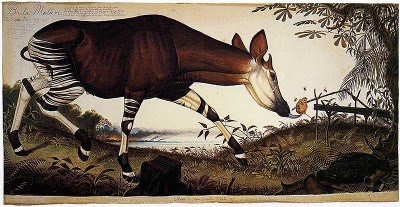

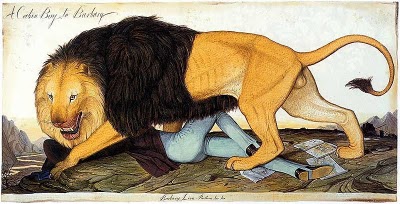

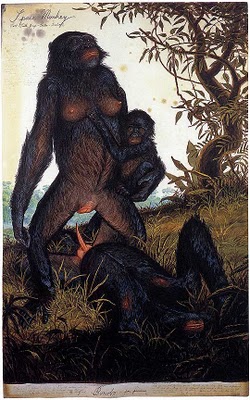

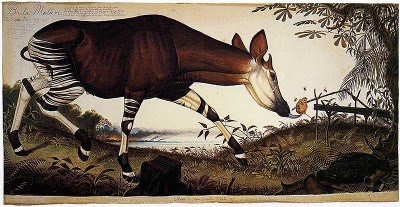

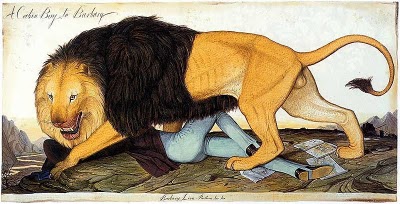

At first glance, Walton Ford’s stunning high definition and large scale watercolors evoke 19th century naturalistic plates made by John James Audubon, George Catlin or Edward Lear. This makes sense, as Walton drew his inspiration from them. When we stare at his pieces, a brand new world is revealed: a complex, uncanny and disturbing one, full of symbols, hidden jokes and references to operatic characteristics related to natural history representative themes.

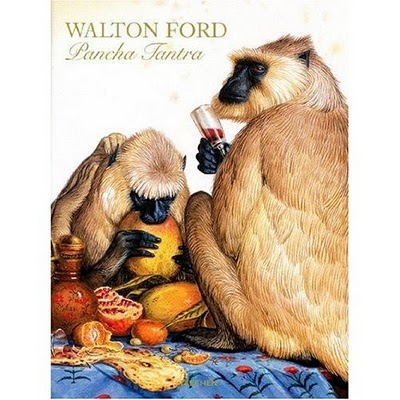

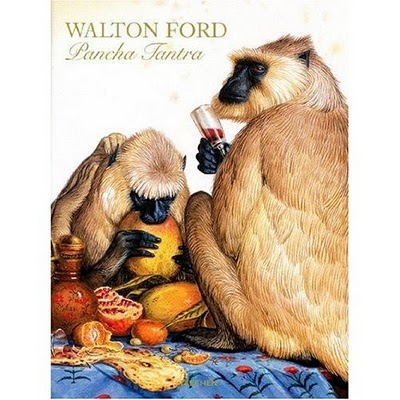

Beasts and birds that wander around in the life-size paintings of this contemporary artist are never mere subjects, but dynamic actors that struggle in great allegorical fights. They are an extensive set of plates that subsequently were scraped together for a de-luxe limited edition of the book Pancha Tantra, released by Taschen. Pancha Tantra is a 3rd century anthology of Hindu animal tales, written in Sanskrit, centuries before La Fontaine or Aesop wrote their fables.

Watercolor techniques demand precision and Walton’s work is nothing if not precise. He stays away from unfinished or sketchy allure. Paradoxically, that kind of impressive hyperrealism that seems an impromptu note is very typical of him. It happens because he thinks nature is always unpredictable. Sometimes wild life is cruel, untamed, irrational, tender, perturbing… in other words, always multifaceted. Nature is never static, although he may paint an animal posing in fraganti.

Marginalia written with elegant old-fashioned calligraphy is an infallible element of his drawings. In these annotations he synthesizes the rest of the exposed message. It is an epilogue, a key that allows decoding the mystery around the image.

His pieces have political commentaries. He said, “I use a source that comes from the period that suits the natural history image, like this Alexander Kingslake book called Eothen, which is a beautiful book. And I try to bring it up to date and think about how it affects the way we think today and how similar the nineteenth century is to now. That moment of empire is almost the same. That moment of fear and first contact and misunderstanding and misapprehension is exactly what we’re going through right now. And we haven’t seemed to figure anything more or less out since then. You still feel like you would be carefully shot and carelessly buried if you made the wrong move.”

Besides Eothen, there are other sources of backing: Benjamin Franklin’s letters; Leonardo da Vinci’s diaries; testimonies from a zoo manager; excerpts from José Martí, Ernest Hemingway or Marquis of Sade’s books; or The Criminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals by E.P. Evans (1906). In Walton Ford’s paintings we can notice an approach to Goya, Rembrandt, Brueghel, Durer, or even Robert Crumb’s humor. Nonetheless, Walton insists that Audubon (the Haitian artist who claimed to be a Jacques Louis David pupil) is his main inspiration.

“Part of the reason I got interested in using watercolor is that I was interested in painting things that looked like Audubons. They were like fake Audubons, but I twisted the subject matter a bit, and got inside his head, and tried to paint as if it was really his tortured soul portrayed. As if his hand betrayed him, and he painted what he didn’t want to expose about himself. And it was very important to me to make them look like Audubons, to make them look like they were a hundred years old—like he painted them but that they escaped out of him. Almost like A Picture of Dorian Gray, but a natural history image.”

“And once I was sort of finished with that, I realized that I sort of did those for my own amusement. And I was doing bigger oil paintings; I was doing constructions at that time. I was doing all kinds of stuff, trying to find my way. You go through these periods in your artistic evolution where you’re trying a bunch of different things out. And that was just one of the things I was trying out at that time. And I felt like it was more successful than most of the other things I attempted to do, partly because I had all these years of drawing, since I was a little kid. So, they were more convincing, right off the bat.”

La Grande Odalisque, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, 1814

La Grande Odalisque, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, 1814 Dresden Venus or Sleeping Venus, Giorgione, 1508-10

Dresden Venus or Sleeping Venus, Giorgione, 1508-10 Portrait of Madame Récamier, Jacques-Louis David, c. 1800

Portrait of Madame Récamier, Jacques-Louis David, c. 1800 Julianne Moore, after Ingres’s La Grande Odalisque. By Michael Thompson, 2000; Vanity Fair, April 2000

Julianne Moore, after Ingres’s La Grande Odalisque. By Michael Thompson, 2000; Vanity Fair, April 2000