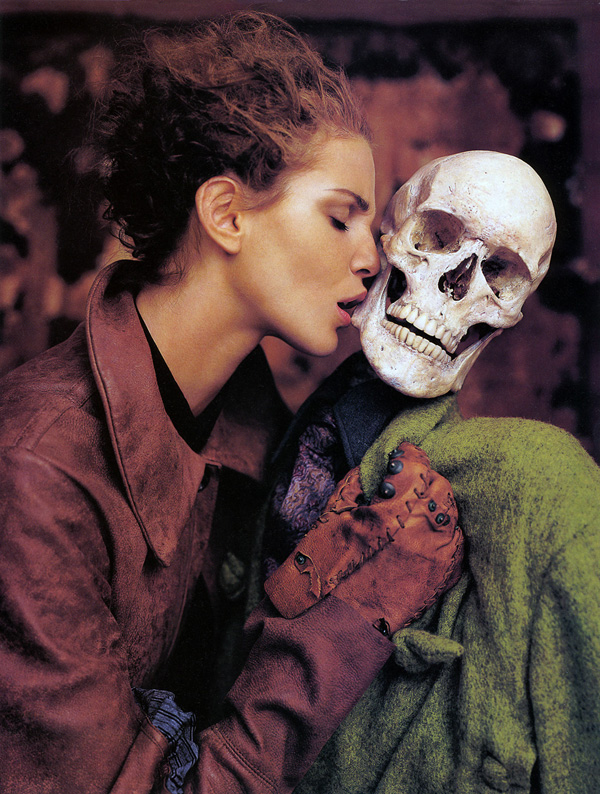

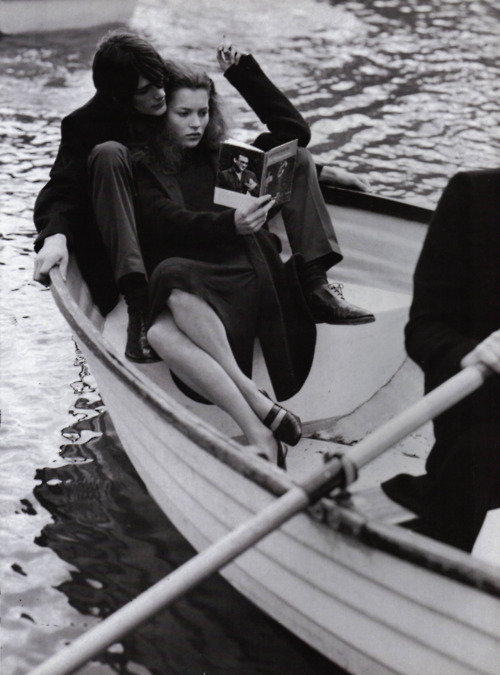

François Truffaut whilst he was in military prison, circa 1951

François Truffaut whilst he was in military prison, circa 1951

After starting his own film club in 1948, François Truffaut met André Bazin, who would have great effect on his professional and personal life. Bazin was a critic and the head of another film society at the time. He became a personal friend of Truffaut’s and helped him out of various financial and criminal situations during his formative years.

Truffaut joined the French Army in 1950, aged 18, but spent the next two years trying to escape. Truffaut was arrested for attempting to desert the army. Bazin used his various political contacts to get Truffaut released and set him up with a job at his newly formed film magazine Cahiers du cinéma. Over the next few years, Truffaut became a critic (and later editor) at Cahiers, where he became notorious for his brutal, unforgiving reviews. He was called “The Gravedigger of French Cinema” and was the only French critic not invited to the Cannes Film Festival in 1958. He supported Andre Bazin in the development of one of the most influential theories of cinema itself, the auteur theory.

In the late 1950s, French New Wave critics, especially Éric Rohmer, Claude Chabrol, Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut, were among the first to see and promote Alfred Hitchcock‘s films as artistic works. Hitchcock was one of the first directors to whom they applied their auteur theory, which stresses the artistic authority of the director in the film-making process.

As critics for the iconoclastic film magazine Cahiers du Cinéma, Godard and Truffaut had shared a similar aesthetic. Their masters were (besides Hitchcock), Jean Renoir, Roberto Rossellini and Fritz Lang, whose films were underestimated at the time and whom they defended with the pugnacity of young prizefighters.

In an article for Cahiers du Cinéma in 1954, Truffaut posited his “auteur theory”: the idea that certain directors, regardless of whether they wrote their films, were the true authors of their work. They reserved their greatest criticism for postwar French cinema, which Truffaut dismissed as “cinéma du papa” for its tendency to churn out tired over-literary adaptations of classic novels and plays.