Sonnets are full of love, and this my tome

Has many sonnets: so here now shall be

One sonnet more, a love sonnet, from me

To her whose heart is my heart’s quiet home,

To my first Love, my Mother, on whose knee

I learnt love-lore that is not troublesome;

Whose service is my special dignity,

And she my loadstar while I go and come

And so because you love me, and because

I love you, Mother, I have woven a wreath

Of rhymes wherewith to crown your honored name:

In you not fourscore years can dim the flame

Of love, whose blessed glow transcends the laws

Of time and change and mortal life and death.

Christina Rosetti

Sonnet

Christina Rosetti and her mother

Christina Rosetti and her mother

My mother had a slender, small body, but a large heart – a heart so large that everybody’s joys found welcome in it, and hospitable accommodation.

Mark Twain

Jane Lampton Clemens Mother of Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain).

Jane Lampton Clemens Mother of Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain).

The daughter of Benjamin Lampton and Margaret Casey, Jane was raised in Lexington, Kentucky. As a young woman of exceptional beauty and wit, and a graceful dancer, she was a favorite of many. A young physician from Lexington, Richard Barrett, gained her love, but such were the mores of the time, they found it difficult to see each other. It seems both felt rejected as a result. She would remember him, and even attempt to find him in later life. It has been said that her engagement to John Clemens was more a matter of temper than tenderness, but after their marriage on May 6, 1823, she proved to be a truly loyal, steadfast partner. She married at the age of 20, and bore seven children, outliving all but three.

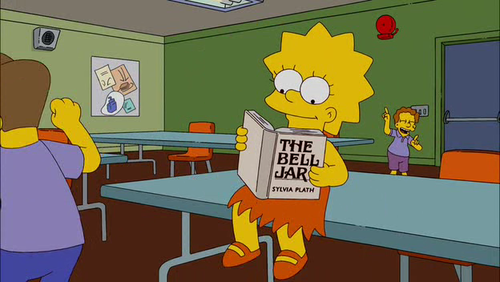

Sylvia Plath with her parents, Aurelia and Otto

Sylvia Plath with her parents, Aurelia and Otto

“Mother, you are the one mouth

I would be a tongue to…”

Sylvia Plath

Poem for a Birthday

Alice MacDonald, Rudyard Kipling’s mother

Alice MacDonald, Rudyard Kipling’s mother

“If I were hanged on the highest hill,

Mother o’ mine, O mother o’ mine!

I know whose love would follow me still,

Mother o’ mine, O mother o’ mine!

If I were drowned in the deepest sea,

Mother o’ mine, O mother o’ mine!

I know whose tears would come down to me,

Mother o’ mine, O mother o’ mine!

If I were damned of body and soul,

I know whose prayers would make me whole,

Mother o’ mine, O mother o’ mine!”

Rudyard Kipling

Mother O’ Mine

Balzac’s mother.

Balzac’s mother.

Anne-Charlotte-Laure Sallambier, came from a family of haberdashers in Paris. Her family’s wealth was a considerable factor in the marriage: she was eighteen at the time of the wedding, and Bernard-François fifty. British writer and critic V. S. Pritchett explained, “She was certainly drily aware that she had been given to an old husband as a reward for his professional services to a friend of her family and that the capital was on her side. She was not in love with her husband.”

The heart of a mother is a deep abyss at the bottom of which you will always find forgiveness.

Honoré de Balzac

Mrs. Maria Clemm

Mrs. Maria Clemm

(Born: March 12, 1790 – Died: February 16, 1871)

Poe’s aunt and, after he married his cousin Virginia, his mother-in-law. Poe called her “Muddy.” Although there is some debate as to whether or not she was a positive influence on Edgar, there seems no doubt that she cared for him like a son and that Poe certainly thought of her as a mother. The poem “To My Mother” (first published July 7, 1849) is clearly dedicated to her.

“Because I feel that, in the Heavens above,

The angels, whispering to one another,

Can find, among their burning terms of love,

None so devotional as that of “Mother,”

Therefore by that dear name I long have called you-

You who are more than mother unto me,

And fill my heart of hearts, where Death installed you

In setting my Virginia’s spirit free.

My mother-my own mother, who died early,

Was but the mother of myself; but you

Are mother to the one I loved so dearly,

And thus are dearer than the mother I knew

By that infinity with which my wife

Was dearer to my soul than its soul-life.”

Edgar Allan Poe

To my Mother

Naomi and Allen Ginsberg

Naomi and Allen Ginsberg

“Strange now to think of you, gone without corsets & eyes, while I walk on

the sunny pavement of Greenwich Village.

downtown Manhattan, clear winter noon, and I’ve been up all night, talking,

talking, reading the Kaddish aloud, listening to Ray Charles blues

shout blind on the phonograph

the rhythm the rhythm–and your memory in my head three years after–

And read Adonais’ last triumphant stanzas aloud–wept, realizing

how we suffer…”

Allen Ginsberg

Kaddish

Robert Louis Stevenson with his mother, wife and step-daughter at their temporary residence, Darlinghurst, January 1893

Robert Louis Stevenson with his mother, wife and step-daughter at their temporary residence, Darlinghurst, January 1893

You too, my mother, read my rhymes

For love of unforgotten times,

And you may chance to hear once more

The little feet along the floor.

Robert Louis Stevenson

To My Mother

Moorish woman and child with gathered drawers with attached stockings. drawing by Christoph Weiditz.

Moorish woman and child with gathered drawers with attached stockings. drawing by Christoph Weiditz.

“Every beetle is a gazelle in the eyes of its mother.”

Moorish Proverb