© Hereus de Roberto Bolaño. Barcelona (Spain), 1981

© Hereus de Roberto Bolaño. Barcelona (Spain), 1981

“…31. Soñé que la tierra se acababa. Y que el único ser humano que contemplaba el final era Franz Kafka. En el cielo los Titanes luchaban a muerte. Desde un asiento de hierro forjado del parque de Nueva York veía arder el mundo.

32. Soñé que estaba soñando y que volvía a mi casa demasiado tarde. En mi cama encontraba a Mario de Sá-Carneiro durmiendo con mi primer amor. Al destaparlos descubría que estaban muertos y mordiéndome los labios hasta hacerme sangre volvía a los caminos vecinales.

33. Soñé que Anacreonte construía su castillo en la cima de una colina pelada y luego lo destruía.

34. Soñé que era un detective latinoamericano muy viejo. Vivía en NuevaYork y Mark Twain me contrataba para salvarle la vida a alguien que no tenía rostro. Va a ser un caso condenadamente difícil, señor Twain, le decía.

35. Soñé que me enamoraba de Alice Sheldon. Ella no me quería. Así que intentaba hacerme matar en tres continentes. Pasaban los años. Por fin, cuando ya era muy viejo, ella aparecía por el otro extremo del Paseo Marítimo de Nueva York y mediante señas (como las que hacían en los portaaviones para que los pilotos aterrizaran) me decía que siempre me había querido.

36. Soñé que hacía un 69 con Anaïs Nin sobre una enorme losa de basalto.

37. Soñé que follaba con Carson McCullers en una habitación en penumbras en la primavera de 1981. Y los dos nos sentíamos irracionalmente felices.

38. Soñé que volvía a mi viejo Liceo y que Alphonse Daudet era mi profesor de francés. Algo imperceptible nos indicaba que estábamos soñando. Daudet miraba a cada rato por la ventana y fumaba la pipa de Tartarín.

39. Soñé que me quedaba dormido mientras mis compañeros de Liceo intentaban liberar a Robert Desnos del campo de concentración de Terezin. Cuando despertaba una voz me ordenaba que me pusiera en movimiento. Rápido, Bolaño, rápido, no hay tiempo que perder. Al llegar sólo encontraba a un vieoj detective escarbando en las ruinas humeantes del asalto.

40. Soñé que una tormenta de números fantasmales era lo único que quedaba de los seres humanos tres mil millones de años después de que la Tierra hubiera dejado de existir.

41. Soñé que estaba soñando y que en los túneles de los sueños encontraba el sueño de Roque Dalton: el sueño de los valientes que murieron por una quimera de mierda.

42. Soñé que tenía dieciocho años y que veía a mi mejor amigo de entonces, que también tenía dieciocho, haciendo el amor con Walt Whitman. Lo hacían en un sillón, contemplando el atardecer borrascoso de Civitavecchia.

43. Soñé que estaba preso y que Boecio era mi compañero de celda. Mira, Bolaño, decía extendiendo la mano y la pluma en la semioscuridad: ¡no tiemblan!, ¡no tiemblan! (Después de un rato, añadía con voz tranquila: pero tamblarán cuando reconozcan al cabrón de Teodorico.)

44. Soñé que traducía al Marqués de Sade a golpes de hacha. Me había vuelto loco y vivía en un bosque.

45. Soñé que Pascal hablaba del miedo con palabras cristalinas en una taberna de Civitavecchia: “Los milagros no sirven para convertir, sino para condenar”, decía.

46. Soñé que era un viejo detective latinoamericano y que una Fundación misteriosa me encargaba encontrar las actas de defunción de los Sudacas Voladores. Viajaba por todo el mundo: hospitales, campos de batalla, pulquerías, escuelas abandonadas…”

Roberto Bolaño

Blanes, 1994

Tres (Fragmento de una colección de poemas)

_______________________________________

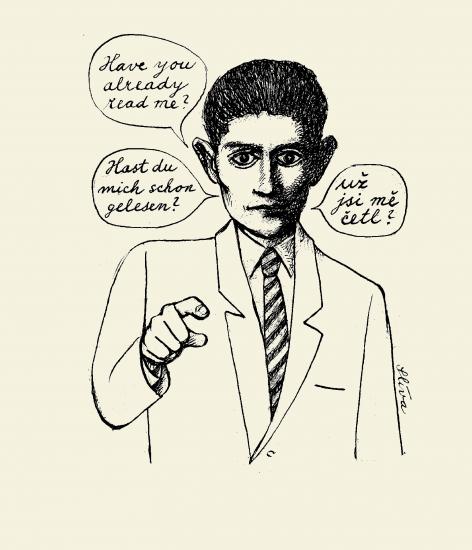

…”31. I dreamt that Earth was finished. And the only

human being to contemplate the end was Franz

Kafka. In heaven, the Titans were fighting to the

death. From a wrought-iron seat in Central Park,

Kafka was watching the world burn.

32. I dreamt I was dreaming and I came home

too late. In my bed I found Mário de Sá-Carneiro

sleeping with my first love. When I uncovered them

I found they were dead and, biting my lips till they

bled, I went back to the streets.

33. I dreamt that Anacreon was building his castle

on the top of a barren hill and then destroying it.

34. I dreamt I was a really old Latin American

detective. I lived in New York and Mark Twain

was hiring me to save the life of someone without

a face. “It’s going to be a damn tough case, Mr.

Twain,” I told him.

35. I dreamt I was falling in love with Alice Sheldon.

She didn’t want me. So I tried getting myself killed

on three continents. Years passed. Finally, when I

was really old, she appeared on the other end of the

promenade in New York and with signals (like the

ones they use on aircraft carriers to help the pilots

land) she told me she’d always loved me.

36. I dreamt I was 69ing with Anaïs Nin on an

enormous basaltic flagstone.

37. I dreamt I was fucking Carson McCullers in a

dim-lit room in the spring of 1981. And we both felt

irrationally happy.

38. I dreamt I was back at my old high school

and Alphonse Daudet was my French teacher.

Something imperceptible made us realize we were

dreaming. Daudet kept looking out the window

and smoking Tartarin’s pipe

39. I dreamt I kept sleeping while my classmates

tried to liberate Robert Desnos from the Terezín

concentration camp. When I woke a voice was

telling me to get moving. “Quick, Bolaño, quick,

there’s no time to lose.” When I got there, all I

found was an old detective picking through the

smoking ruins of the attack.

40. I dreamt that a storm of phantom numbers was

the only thing left of human beings three billion

years after Earth ceased to exist.

41. I dreamt I was dreaming and in the dream

tunnels i found Roque Dalton’s dream: the dream

of the brave ones who died for a fucking chimera.

42. I dreamt I was 18 and saw my best friend at

the time, who was also 18, making love to Walt

Whitman. They did it in an armchair, contemplating

the stormy Civitavecchia sunset.

43. I dreamt I was a prisoner and Boethius was

my cellmate. “look, Bolaño,” he said, extending

his hand and his pen in the shadows:

“they’re not trembling! they’re not

trembling!” (after a while,

he added in a calm voice: “but they’ll tremble when

they recognize that bastard Theodoric.”)

44. I dreamt I was translating the Marquis de Sade

with axe blows. I’d gone crazy and was living in the

woods.

45. I dreamt that Pascal was talking about fear with

crystal clear words at a tavern in Civitavecchia:

Miracles don’t convert, they condemn, he said.

46. I dreamt I was an old Latin American detective

and a mysterious Foundation hired me to find the

death certificates of the Flying Spics. I was traveling

all around the world: hospitals, battlefields, pulque

bars, abandoned schools….”

Excerpt from Tres (a collection of poetry)

English translation by Laura Healy

Cover designed by Alvin Lustig in 1946

Cover designed by Alvin Lustig in 1946