Le Viol (The Rape), René Magritte, 1934

Le Viol (The Rape), René Magritte, 1934

The Rape, one of Surrealism’s most powerful images — Georges Bataille could never suppress a nervous laugh whenever he was confronted by this painting — likewise works with a subversive idea. The selection of the work’s title indicates the ongoing conflict of a voyeur; René Magritte comes very close here to Hans Bellmer’s erotic perversion, albeit without the latter’s sadness.

In 1935, Andre Breton published his speech Qu’est-ce que le Surrealisme? with Magritte’s drawing, Le Viol on its cover. The image, a view of a woman’s head in which her facial features have been replaced by her torso, was meant to shock the viewer out of complacent acceptance of present reality into “surreality,” that liberated state of being which would foster revolutionary social change. Because Le Viol is such a violently charged image and because of the claims made for it by Magritte for its revolutionary potential, the drawing has been the subject of many arguments, both for and against its effectiveness. The feminist community has had a particular interest in this image (and in Magritte’s work as a whole) not only because of the controversial treatment of the female subject in Le Viol, but also because of the ways in which our culture has been so easily able to strip surrealist images of their political content and subsume them back into mainstream culture for use in those very categories of social practice which Surrealism wanted to eradicate.

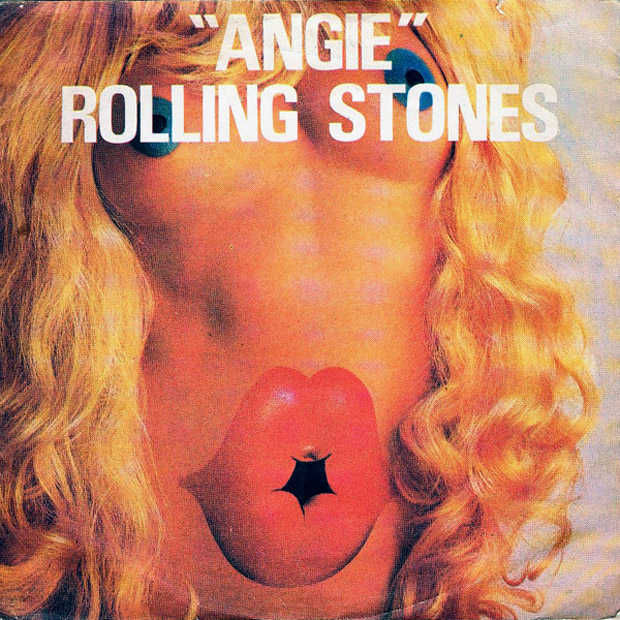

Angie is a song by the rock band The Rolling Stones, featured on their 1973 album Goats Head Soup.

Contrary to popular belief, the song was not about David Bowie‘s first wife Angela or Angie Dickinson; nor was it about Keith Richards‘ first daughter, Dandelion Angela. The song was written before the sex of his upcoming baby was known. He says in his memoir, Life: “I just went, ‘Angie, Angie.’ It was not about any particular person; it was a name, like ‘ohhh, Diana.’ I didn’t know Angela was going to be called Angela when I wrote Angie. In those days you didn’t know what sex the thing was going to be until it popped out. In fact, Anita named her Dandelion. She was only given the added name Angela because she was born in a Catholic hospital where they insisted that a ‘proper’ name be added.”

(Life, p. 323, Ch. 8.)

To listen to this song, please, take a gander at The Genealogy of Style‘s Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/pages/The-Genealogy-of-Style/597542157001228?ref=hl